Throughout media of all forms, we are hungry for information on coronavirus. Some of this is a flat out are-we-doing-better-or-worse-than-they-are, but most of it is simply to try to put what we know into some sort of context that is relevant to our lives.

None of us have much luck with that.

In part it is the nature of data collection during crisis period. Most health care professionals are more interested in saving the life in front of them than typing data into a spreadsheet. But mostly it is because all data is a product of its local circumstances:

In China, even before one considers political motivations, the system strongly discourages the passing on of bad news. As concerned as the Communist Party is with its international image, it is far more concerned with domestic popular responses to continued negative news. That and the Chinese government has a, shall we say, fluid relationship with data. And yet to this point data out of China is still the only large data set on coronavirus infections we have.

I’ve been waiting for some time for South Korea – a country with a great health care system and a strong respect for the application of science. Unfortunately, their “epidemic” is nothing of the sort. Until very recently, half of South Korea’s cases could be traced back to a single megachurch. It’s very useful as a cluster study and wow does it underline the impact of early, wide-spread testing, but it really isn’t the sort of broad-reach dataset that involves multiple regions and age groups that I was hoping to be able draw conclusions from.

Even “worse” most of Korea’s cases at that church involved young people. Their preponderance in the data skews Korea’s mortality data down significantly, so don’t fool yourself. The Korean experience to date of low mortality is not attainable for the United States because it hasn’t been a true broad-based epidemic.

Data out of Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore are similarly less than useful as their systems were so strongly proactive that none of the three ever really had epidemics to study.

Next up is Italy, where the local health system was simply overwhelmed unexpectedly. By the time the Italians realized what was happening, hospitals were overflowing. That prevented meaningful testing regimens anywhere outside of the hospitals themselves. Since the virus tends to trigger more severe cases in older patients, only about 10% of Italy’s confirmed cases were in people under age 40, while 70% are among those over age 50. That’s hardly representative.

It shouldn’t be a surprise that Italy’s data shows a death rate far above that of anywhere else. Italy is only now – in the fourth week of their epidemic – doing any significant testing outside of hospitals. So don’t overly fret. While South Korea’s low mortality figures are not America’s future, neither are Italy’s high ones.

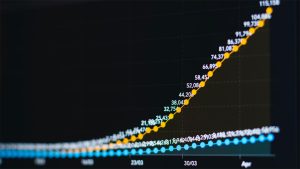

All these countries’ experiences hold lessons for all of us, but what they do not hold are clear points of comparison. All the data must be absorbed within the context of which it was produced, in addition to being understood at a specific moment in time. (For the purposes of this post, the data in question is all from March 26.)

We still don’t have a reasonable understanding of the American data because we simply don’t have enough, but we are getting there. As of March 27 the United States has the results from over 500,000 tests, but as of March 19 we had only completed 100,000. The US is only now beginning to get its first look at viral penetration in its primary centers of inflection – and only its primary centers of infection. Testing will continue to increase rapidly both in number and in geographic reach, but kinks in the supply chain remain. Progress will not be in a straight line.

Which means the best comparative data the United States is likely to get before the epidemic washes over the country will be out of Spain and France, a pair of countries who had enough forewarning to begin at least some sporadic testing before their health systems were hit hard. Their data may be the best available, but as their epidemics are likely to occur no more than two to three weeks ahead of America’s, there will not be much time to parse and draw lessons from it.

And none of it will be of use to New York City, which appears likely to suffer its heaviest caseloads right along with the Spanish and French.