In the age of coronavirus, Europe’s near-term future is bleak.

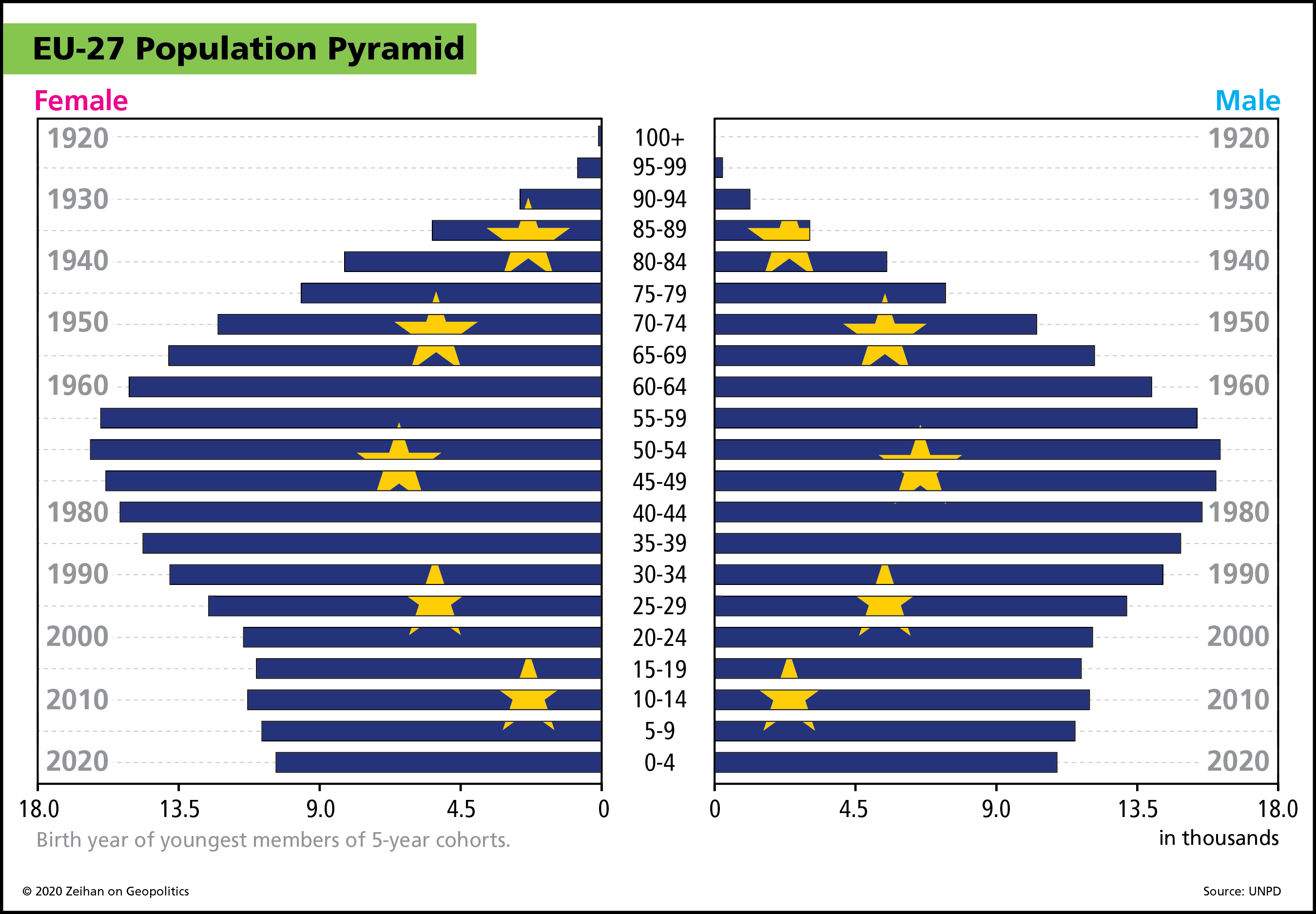

European headlines in coming weeks will be about coronavirus deaths. In large part the issue is demographic. Coronavirus is far more likely to kill those over aged 60. The average European is approximately a half-decade older than the average American. Only the Japanese are older.

Specifically, Italy hosts the world’s second-oldest population, while Germany ranks 5th. Meanwhile, many of the “new” European countries in Central Europe are not all that much younger, while also lacking German- or Italian-quality health care. Others, Ireland, Greece and Spain come to mind, have had to deal with financial crisis by cutting services. Services like health care. The United Kingdom, courtesy of the dual forces of Brexit and coronavirus, are seeing many health care professionals who are not UK citizens but who were able to work in the UK during the Kingdom’s EU membership, fleeing back to their home countries at the worst possible time.

The demographic issue will hurt Europeans on more than simply mortality figures.

People under 45 tend to be a society’s big spenders. They buy cars and homes. They go to university. Such consumption is what drives most modern economies. But not in Europe. Europe’s young cadre is thin and getting thinner by the year. Most European countries – Italy and Germany most notably – have already aged to the point that any sort of demographic rebound is now impossible. They simply don’t have enough people who could even theoretically have children. There certainly aren’t enough people of the right age demographic to drive a consumption-driven rebound.

Which makes mitigating the economic damage of coronavirus structurally impossible. The sort of consumer stimulus which is the backbone of consumer-focused, anti-recession efforts in the United States simply wouldn’t work in Europe. On the whole, the European Union has aged into being little more than an export union. And in a time of global travel restrictions and virus-forced collapses in income and consumption, there just isn’t anyone to export to. All Europe can do is shelter in place, pray their health systems hold, and wait for the world to restart. So long as the coronavirus is impinging activity anywhere, a sustained European economic recovery is impossible.

But even if Europe had a favorable population structure, it lacks the institutional structure to hold the line against the virus anyway. It comes down to money.

Having its own currency enables the United States to print however much money it wants to risk, using that money to fund its own deficit spending. Neither W Bush nor Obama nor Trump would ever be confused with fiscal conservatives, but even now at the very beginning of the process we are seeing spending bloat unprecedented in American history – even at the height of World War II. By the second week of April, the Americans will have pumped over $2 trillion in financial relief into their system, or roughly 10% of GDP, in addition to monetary stimulus of a volume that stuns the imagination. The current spending wave has already seen the Federal Reserve hoover up over $1 trillion in securities, while the federal government is putting up to $1200 into the hands of the vast supermajority of American adults, with a $500 kicker for each child. Nor will this be the last such infusion. Expect another one sometime in the summer.

Europe lacks that sort of power and flexibility.

Part of the network of treaties that underpin the common European currency mandates not only fairly strict deficit ceilings (although those ceilings were suspended over the weekend) but far more importantly the Maastricht Treaty on Monetary Union took monetary responsibility out of member governments’ hands. European states can’t print currency. If they want to deficit spend, they have to raise the funds themselves. That takes time. That takes investors willing to put their money into governments’ hands.

Now technically, the European Central Bank can expand the money supply, and it will, but there are two problems. First, Europe never truly recovered from the 2008 financial crisis. Eurozone interest rates have been negative for years. What about unconventional measures? Much ballyhoo has been made in the United States about how the Federal Reserves purchased scads of bonds to prop up markets, purchases which peaked at just shy of 25% of GDP at the height of the financial crisis. The ECB’s balance sheet as of January 1, 2020, after a decade of calm and before coronavirus erupted, was twice that in relative size. It isn’t clear the ECB has much ammo to use here, conventional or unconventional.

Second, any ECB action raises the issue of whose bonds will the ECB buy? Will it be the country with the most likely chance of repayment (Germany), or the country facing the worst health crisis today (Italy), or the country likely to see the highest death rate (Spain), or the country in the worst financial position (Greece)?

Every time the Europeans face any sort of question that bridges the monetary and the budgetary, the eurozone finance and prime ministers have to meet to hash out their disagreements in marathon negotiating sessions that take days (if not months). In times of calm this is a questionable system which often borders on the comical. In times of crisis it is really really really really stupid.

It shows in the outcomes. During the 2008 financial crisis the Americans did more mitigation in three weeks than the Europeans did in nine years. This time around, the Americans did more in 48 hours than they did during the entire financial crisis.

The funding America’s Small Business Administration made available to provide bridge financing for America’s small businesses is a case in point. On day one $50 billion was unleashed, with another $350 billion to be available by April 1. The EU has no such established facility. Individual European governments are scrambling to raise the necessary cash for their own small businesses. Weaker EU states are unlikely to be able to raise the requisite funds without raiding their already rickety banks. With quarantines in place, entire countries shut down. Add in Europe’s far less flexible labor market and a workforce which remains wedded to old-style set-location facilities means European firms have more need for bridge financing than American ones, yet even Europe’s capacity to provide that financing is far lower.

Europe today is just getting going with its Rube-Goldberg-like-decisionmaking machine, and this time around coronavirus quarantines prevent the European leadership from even meeting in person to hash out a plan. The only European leader with gravitas, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, is in isolation due to potential coronavirus exposure.

Which means “Europe” cannot be part of the mitigation process.

That leads us six places, none of which are good. First, European investors know all this and they aren’t flooding their money into European assets. Instead, it’s a massive flight to US dollar assets. Expect the USD to continue to rise throughout the crisis.

Second, an exception to that rule will only increase the light between the various European governments. Germany, unlike most of Europe, has steadily whittled away at its debt levels to the point that pre-crisis there was a shortage of high-quality, low-risk government debt on European financial markets. With Germany loosening the purse strings, investors will purchase German debt. It is the bulk of the rest of Europe that’s likely to be shunned. Deep, visceral splits between how the Germans and the bulk of the Union viewed finance existed before coronavirus.

Debates on the topic are already taking on the stench of desperation. On March 25 the leaders of France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, Luxembourg, Slovenia, Belgium and Greece (aka countries who consistently find balancing their checkbooks difficult) called upon the EU to issue a joint debt instrument to deal with coronavirus. Germans are likely to have a different opinion.

Third, when the scale of the capital flight and budgeting shortfalls becomes apparent, when European governments realize the money they need to try to save their systems is leaving, they will take action. Expect strict European capital controls at all levels. (China of course already has capital controls. Expect them to intensify.)

Fourth, the controls won’t be nearly enough. Even if the Europeans could prevent capital from leaving, raising capital to fund emergency spending the old-fashioned way isn’t as quick or effective as the American method of simply flipping the switch on the printing press. Firms would fold in the thousands, and the damage will not be limited to the small players. To stave off the subsequent economic and cultural carnage, expect mass nationalizations throughout European economies. Unsurprisingly, the French are already discussing the mechanics of how to manage this. Peugeot, Renault and Airbus have already indicated they will fight the process (although they’d still love help with recapitalization and operating costs).

Fifth, this is likely the end of “European” manufacturing. The European manufacturing system, especially the German manufacturing system, is based on the free movement of goods, people and capital across borders. That simply isn’t possible in an environment of national quarantine, capital flight, capital controls and nationalizations. Post-crisis things will still be made in Germany and Bulgaria and Sweden and so on, but not all that much is likely to be the result of a multi-national European supply chain.

This is doubly problematic in the short term as most European countries lack even small pieces of the medical supply chain. While the US can retool and China can get back to work, many European states simply don’t have anything within their borders they can use.

The dream of Europe was that open borders would enable Europe to have economies of scale of the Chinese or American type. But these are still separate countries, and the utter inability of the EU to ride to the rescue leaves individual states more or less on their own at the worst possible time. Germany, for one, is a major exporter of medical equipment, and it has already barred exports of many coronavirus-related materials. Even to its EU partners. Many Europeans already resent Germans’ unwillingness to share their wealth. Imagine how refusal to share medical equipment will go over once the death toll gets seriously scary.

Sixth, this is the end of the European economic and social model, and it risks being the end of “Europe” as an entity.

- Europe’s demographics make consumption-led growth impossible, even as coronavirus blocks export-led growth.

- The Americans were backing away from the global security rubric that makes Europe’s export-led growth model possible before coronavirus, and the virus is only accelerating America’s turning-inward.

- Europe lacks the institutional capacity to manage crisis response.

- Europe lacks the financial capacity to cope with the crisis, much less apply the sort of financial fire-hose the Americans did almost reflexively.

- Dealing with the virus’ spread has already forced the Europeans to abandon the free movement of people.

- Dealing with their financial shortfalls will force them to abandon the free movement of capital.

- Dealing with mass nationalizations and the loss of export markets will force them to abandon the free movement of goods.

That’s three of the four freedoms upon which modern Europe relies. The fourth freedom – movement of services – was largely something that only the UK cared about, and the Brits are gone.

There is one possible “solution” to these problems: drop the euro.

If the Maastricht Treaty were abrogated (or at least suspended) and national control over monetary policy reintroduced, individual European countries could then engage in unlimited quantitative easing, both to mitigate the current crisis and to help manage the subsequent damage and recovery. This would (obviously) hold (many) downsides, but if the goal is to have the necessary capital required to address the current crisis, this is the only path I see that still results in salvaging Europe’s current economic and social structure.

In theory, once coronavirus was in the rear-view mirror, Europe could go through the process of re-merging their currencies (perhaps this time without basket cases like Greece). Yes, I realize this would be monumentally messy, but we’re already in a world where economic and financial norms are in abeyance. Most of contemporary Europe’s “messes” require extensive multi-national negotiations. This “plan” has the advantage of countries doing things themselves.

Regardless of the path forward (or down) coronavirus is just the beginning of Europe’s problems. Demographics, economics, financials, supply chains, none of it works under coronavirus – and coronavirus is going to be with us until we either get a vaccine, herd immunity or mass serological testing, none of which is particularly likely to happen in 2020. Even then, it is far from clear that Europe as we know it can reconstitute in the world after coronavirus. And never forget that all Europe is not created equal. Germany is not France is not Italy is not Poland is not Sweden is not Portugal is not Romania.

An end to the concept of “European” being singular represents more than simply the return to the norm of European history, it removes one of the central pillars of the world we know. That cascading failure and the reordering to come will be a subject in subsequent installments in our Coronavirus Guides series.

And now the pitch: the Coronavirus Guides are our primer documents, intended not to finish the discussions of this or that topic, but to launch them. Contact us at Zeihan.com/consulting to inquire about rates and scheduling options for teleconferences, videoconferences and in-depth consulting calls.