With cold fronts rushing through much of the country, the Texas power grid had lots of eyes on it this past week. Thankfully, some “updates” over the past couple years have helped the Texans avoid catastrophe.

There’s a handful of reasons this storm was weathered: a shorter cold snap, regulatory changes, and structural updates. The first one is self-explanatory, but let’s breakdown the last two.

Governor Abbot introduced a series of winterizing efforts following the 2021 crisis, which enabled the natural gas system to continue operating through the storm. The winterizing technology used is over 50 years old, so I use the term – updates – loosely.

As for the structural updates, Texas is a bit ahead of the game; they’ve introduced some ‘Texas-sized’ wind turbines and expanded solar capacity. Combine the expansion in clean energy and a more reliable natural gas baseload system, Texas had its bases covered.

These changes made in Texas are just one example of how global energy systems will adapt and evolve over the next few decades.

Here at Zeihan On Geopolitics we select a single charity to sponsor. We have two criteria:

First, we look across the world and use our skill sets to identify where the needs are most acute. Second, we look for an institution with preexisting networks for both materials gathering and aid distribution. That way we know every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence. Then we give what we can.

Today, our chosen charity is a group called Medshare, which provides emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it. Until future notice, every cent we earn from every book we sell in every format through every retailer is going to Medshare’s Ukraine fund.

And then there’s you.

Our newsletters and videologues are not only free, they will always be free. We also will never share your contact information with anyone. All we ask is that if you find one of our releases in any way useful, that you make a donation to Medshare. Over one third of Ukraine’s pre-war population has either been forced from their homes, kidnapped and shipped to Russia, or is trying to survive in occupied lands. This is our way to help who we can. Please, join us.

TranscripT

Hey, everybody. Winters here. I’m coming to you from Eastern Washington. And today we’re going to talk about winter in Texas. Now, if you guys remember back a couple of years and it was 2021, Texas got hit by a cold storm and basically everything collapsed. All of their energy generation, especially natural gas, just ceased functioning and 200 people died over the course of a couple of weeks because of the loss of electricity.

That has not repeated with this cold front, even though by many measures in most parts of the state, temperatures got a little bit lower. So five things are different now compared to what happened back in 2021. First of all, while it did get as colder, even a little colder, the cold snap wasn’t quite as long. It didn’t last like the two and a half weeks like it did last time.

So the system wasn’t put under as much long term stress. But the bigger issues have to do with organizational and structural changes that the Texans have implemented. The big driving factor for things on the legal side of the regulatory side was Governor Abbott, who had spent a lot of time before 2021 making fun of California for the rolling brown and blackouts because they just have a horrible grid and a horrible energy system.

And then, of course, in Texas you had two or two people die. So he was personally motivated to make some changes and he pushed them through the legislature, which forced the regulatory structures in Texas to adjust. And the biggest part of those changes affected the natural gas industry. So Texas, before 2021 didn’t have its natural gas system winterized at all.

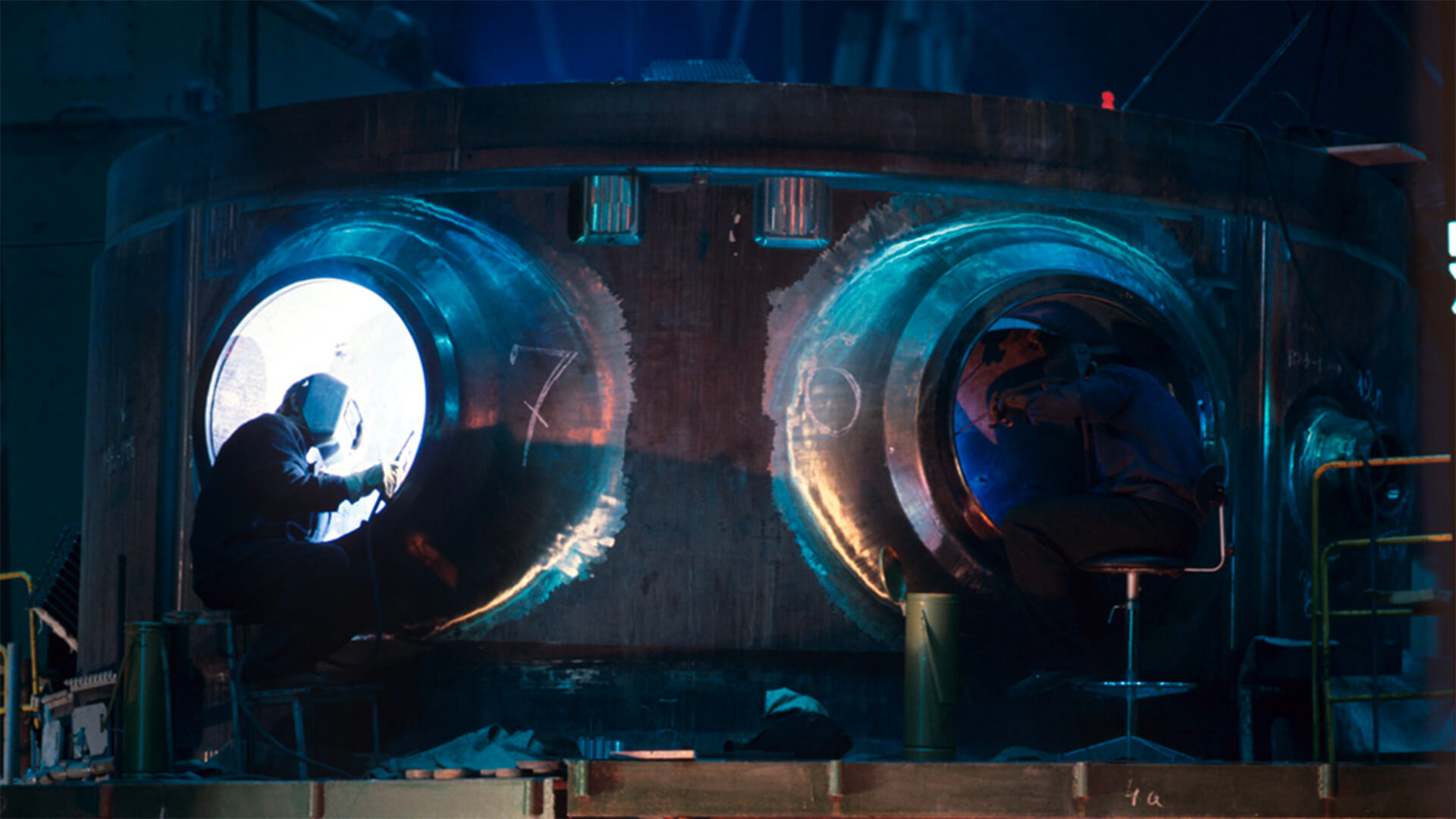

And there’s a lot of water vapor that comes up as a byproduct of natural gas production. And a lot of time it’s in the gathering pipes. So what would happen when we got to subfreezing temperatures is that water vapor would condense into liquid and you go virtually condense into ice and then clogged the pipes. So the entire system across, especially northern Texas in the Dallas area, froze up.

And so there was no fuel to burn, to do everything else. For political reasons, Abbott blamed the wind industry because, you know, when dad stopped going, but it was mostly natural gas that carries the backbone of power generation in Texas, and that is what failed most spectacularly. So in order to get things going, they actually had to waive almost all of their safety regimens and regulations and people were going out with acetylene torches to manually melt the pipes.

And of course, natural gas is flammable explosive. So we were kind of lucky that that didn’t get completely out of hand anyway. This time around, the changes in regulations forced producers across Texas to actually implement some of the best winterizing technologies that we had back in the 1960s. And the Texas grid now is on par with where Arkansas, Oklahoma and New Mexico were about 1975.

So, you know, this is some really basic stuff when it comes to things like insulation. Anyway, it was more than enough to make a difference. Okay. So that was the first big structural change. The other big structural changes had nothing to do with regulation. It’s just how things have evolved. So the new turbines, wind turbines that the Texans had put up more than 200 feet taller than the ones that were up three years ago.

And that means they reach higher. They tap stronger air currents that are more reliable. So even though the wind did drop, we hadn’t seen nearly the drop off in power generating capacity because the physical structure is now different. Second, Texas has put up a whole lot of solar. And when these winter storms come through Texas, usually what you get is a lot of wind, a lot of freezing rain, maybe some snow.

And then once they blow through, it’s cold. Well, but it’s clear air. And so when you have temperatures in the twenties, solar doesn’t really care what the temperature is unless it’s like crazy lower, crazy high. So solar was generating near record energy for the time of year. So you had two different streams of energy coming into the electrical system that they didn’t really have last time.

And they’re baseload system with natural gas worked a lot better than it did. This sort of change is the sort of thing we’re going to see in some way across not just Texas, but the entire country, the eventual world. We’re seeing more and more wind and water and more solar. And it doesn’t always go right the first time.

And we discover that meshing these systems together is more problematic than kind of the breezy things that the Greens say. But when you have multiple systems that do feed into the same network, you do get a lot of redundancy when one works and the other doesn’t. The trick is to make sure you have enough spare capacity that you can dispatch at any given time.

Now, in the past, solar and wind aren’t very good at that because you can’t dispatch them. If the sun’s out, out of the wind’s not blowing, they’re kind of useless. And you have to rely on older fossil fuel. Things like natural gas. But what we’re seeing in Texas specifically, as it were, already seeing turbines that are 800 meters tall.

But in the next year or two, we’re going to be pushing the kilometer tall barrier and again, stronger currents, more reliable use for baseload. So I don’t mean to suggest that all of these problems when it comes to storms and interruptions are going to go away. But as the technology evolves, we’re getting better able to adapt and having a little bit more insulation on the back side as well.

That’s it for me.