In the past couple of weeks coronavirus cases outside of China surged. Particularly worrisome clusters emerged in South Korea and Iran, countries which serve as transport hubs for their respective worlds. US President Donald Trump is doing his normal rambling press conference thing, contradicting most of what little information that is out there. Data coming out of China is more positive, but the idea that China and only China has cracked the code on how to stop a highly virulent virus from spreading in dense population centers is, in a word, dubious. Is anyone not feeling at least a bit…twitchy?

Let’s shift the conversation: Coronavirus may be the most positive thing that’s happened to the global economy in recent years.

China is the world’s workshop. There are precious few complex manufacturing supply chains that don’t link to the mainland in at least some way, with computing, electronics and automotive by far the most exposed. China represents a bit more than a fourth of global manufacturing output all on its own and sports seven of the ten busiest container ports in the world.

The two zones in China most impacted by coronavirus are the Pearl Delta and Yangtze Valley. Most of the 150 million people in China under some degree of involuntary quarantine reside in these zones. The Pearl and the Yangtze are the two most technologically advanced portions of the country, sporting the most sophisticated industrial bases. These regions are by far the most internationally connected of China’s population zones.

The viral epicenter city of Wuhan is one of the largest automotive manufacturing centers in China. Nissan and Honda alone manufacture nearly 2.25 million automobiles there annually. Dongguan, a city in the Pearl River Delta, is known as “the world’s factory” and on its own produces an estimated one-fifth of the world’s smartphones and one-tenth of its shoes.

We’ve all read about how this or that product or company or industry faces pressure from the Chinese shut-ins. So far, shipping companies have cancelled over 80 sailings of container ships, meaning that tens of billions of dollars of goods, many of them inputs into other goods, either weren’t produced or couldn’t get where they needed to go. The sudden lurch in China’s $70 billion annual auto-parts exports industry is already stalling automobile manufacturing in South Korea and Eastern Europe.

But here’s the thing: China’s position in the global system is artificial, and it was going to end anyway.

A look back:

To distill America’s entire Cold War strategy: the Americans created a global Order to provide an economic incentive for membership in their military alliance network. The Americans broke the empires and paid everyone to be on their side against the Soviets. Of the many unintentional side effects was the fostering of an environment where no one shot at anyone else’s shipping, no matter how valuable that shipping might be.

In absolute terms, China is by far the biggest beneficiary of this American-led Order. Japan and the Europeans had carved Chinese territory into imperial spheres of influence. The Americans ended that. China’s manufacturing prowess required the economies of scale of all China being under a single government system. The Americans enabled that. China’s import-export model requires freedom of the seas for commercial shipping to sale the ocean blue without military escort. The American Navy guaranteed that. Without the American-led Order, the Chinese would have never been able to unify or industrialize or modernize or urbanize.

Today, as the Americans step back, there is less than zero hope for the Chinese to step forward. China’s navy is short-range, designed to recapture Taiwan. Convoying clusters of slow-moving supertankers to and from the Persian Gulf is simply beyond China’s capability, much less enforcing the sort of all-ocean maritime safety that the Americans have done as a matter of course these past seven decades.

If anything, it is worse than it sounds.

Energy: China has had no equivalent of the American shale revolution. As the Americans have achieved net energy independence, the Chinese have quadrupled down on becoming the world’s largest oil importer, with the bulk of their oil needs sourced from none other than the Middle East. China lacks the ability to convoy tankers to and from the region (past oil-importing regional rivals Japan, Taiwan, Vietnam and India no less), much less intervene in a way that might preserve oil flows in the way the United States has done almost pathologically these past seven decades.

Agriculture: Some 80% of global foodstuffs can only be produced with imported inputs, whether that input be fuel or fertilizer or fungicide. China has plowed under its best farmland to build all those factories, making the country more input-dependent than most: China today uses some five times the inputs per unit of food of American farmers and still hasn’t achieved food self-sufficiency. In a world without trade China can neither import sufficient foodstuffs from a continent away nor grow its own. Failures in food distribution have crashed far more governments than war or disease. Just ask Mao how he rose to power.

Manufacturing: Modern manufacturing is a logistical marvel that taps hundreds of facilities in dozens of countries, but that system is based on frictionless international trade. Break just a few links and the entire network collapses. A modern car has about 2000 parts. If you are missing ten, you’ve got a large paperweight. Even if the Chinese could somehow magically maintain their globe-spanning supply chains without a globe-spanning navy, there remains the question of who would buy everything?

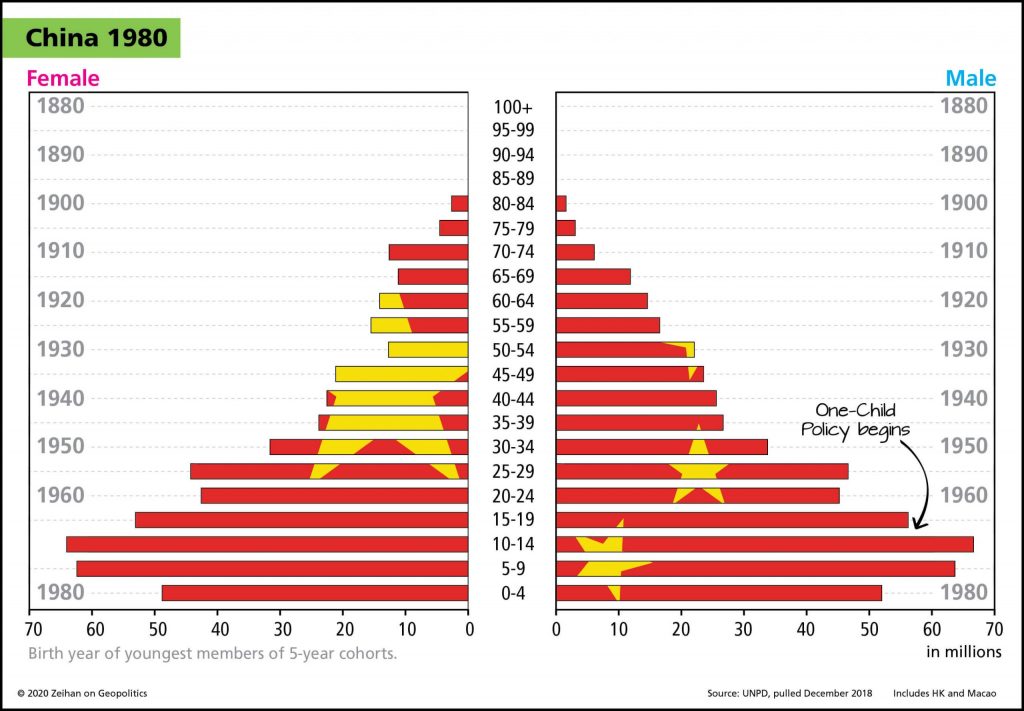

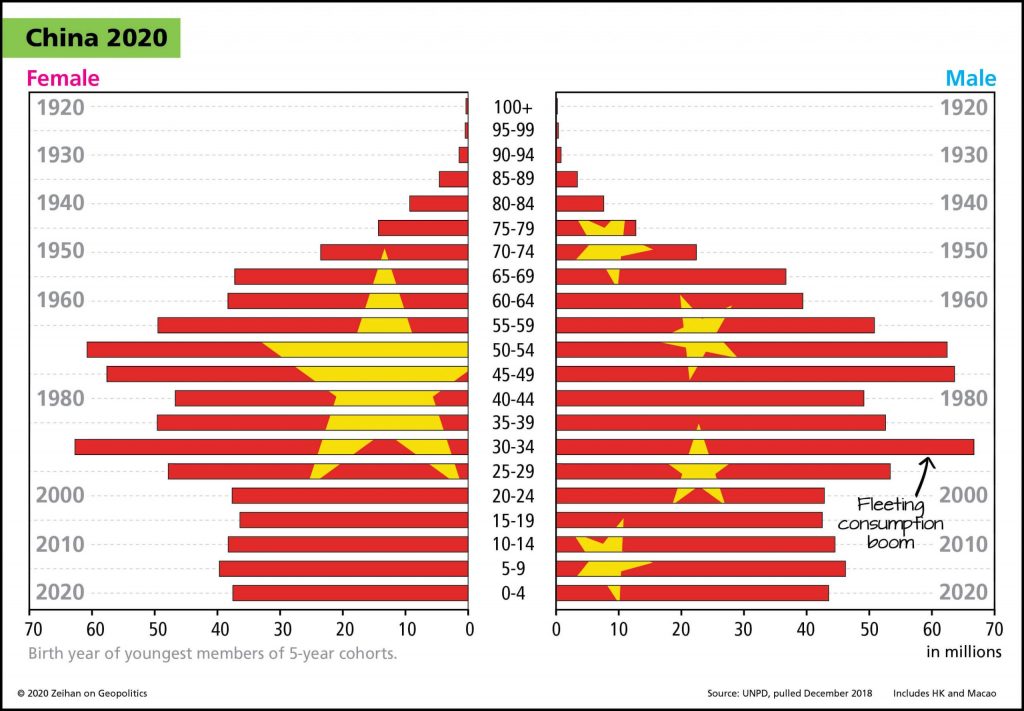

Demographics: The One Child Policy has gutted the country’s next generation of consumers far more effectively than anything the Cultural Revolution or Great Leap Forward ever did. The mean Chinese aged past the mean American about two years ago, so a consumption-led system at home is simply off the table. Slow-moving aging throughout the bulk of the world is doing something similar in Europe and Canada and Brazil and the former Soviet Union and Japan and Korea. Even if somehow the Chinese could make their manufacturing system work without the American security blanket, the export-based model upon which contemporary China is based would have ended this decade anyway for want of consumers.

In a world where the Americans do the security heavy lifting and guarantee the world access to their consumer market – one of only a few that will not contract in the 2020s and 2030s – China’s global integration efforts aren’t simply smart, they are doomed to succeed. In a world in which the Americans’ step back and the rules by which the world works change, China is doomed to do the other thing.

Which means coronavirus is giving us a rare gift. A glimpse into a future without globalized manufacturing in general, but in specific a glimpse into a world without China.

Any company or industry that can weather the suspension of industrial activity in the Pearl and Yangtze should be able to manage the coming global collapse with relative ease. Any that can’t, well, they now know precisely where their exposures are. The question now is whether impacted firms treat this as a one-off or the serendipitous peek that it is.

My new book Disunited Nations: The Scramble for Power in an Ungoverned World published March 3. It contains a big fat trio of chapters on what makes for successful empires and countries, much of which focuses on China. Spoiler alert: It doesn’t look good