As the US attempts to reshore many previously outsourced industries, the Chinese are looking for any opportunity to retain their competitive edge…so let’s talk about solar panels.

China isn’t known for its grand technology or innovation, but through a mix of labor, security and scale, they have emerged as the dominant manufacturer of solar panels.

China’s not letting go of the reins anytime soon. So what will happen next…Industrial espionage? Technology theft? One way or another, the US is bringing solar home.

Prefer to read the transcript of the video? Click here

February is here and that means the Webinar is only 17 days away!

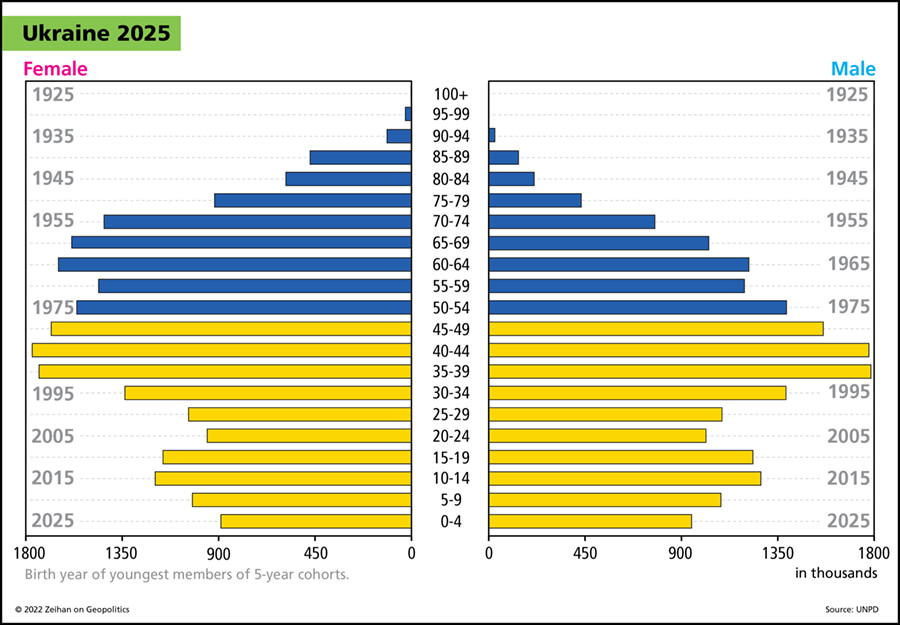

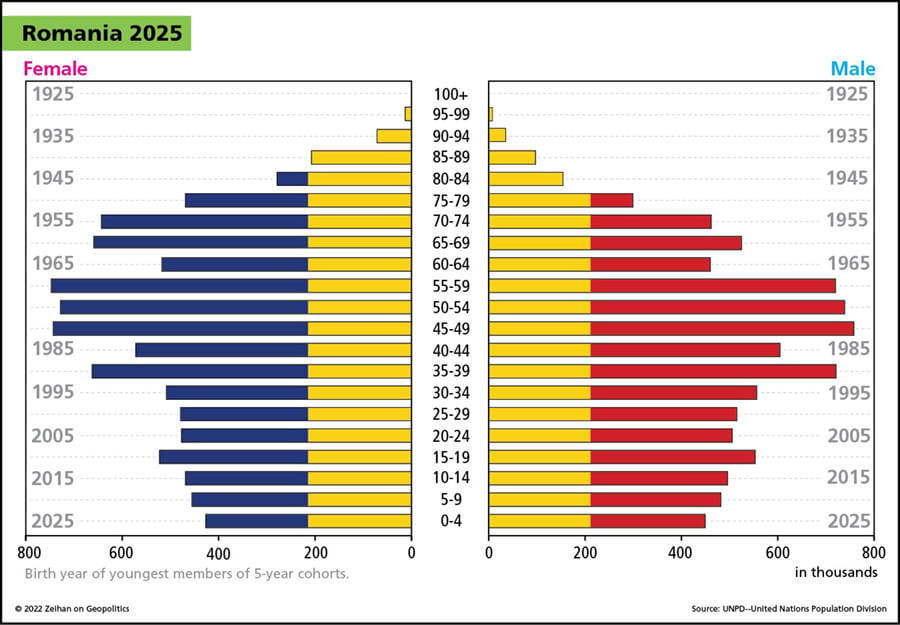

Join me on Feb. 17th for the webinar – Global Outlook: One Year into the Ukraine War. We’ll dive into the global impacts the war has had on supply chains, agriculture, and much more. After my presentation we’ll have a Q&A portion to answer all those burning questions.

Here at Zeihan On Geopolitics we select a single charity to sponsor. We have two criteria:

First, we look across the world and use our skill sets to identify where the needs are most acute. Second, we look for an institution with preexisting networks for both materials gathering and aid distribution. That way we know every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence. Then we give what we can.

Today, our chosen charity is a group called Medshare, which provides emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it. Until future notice, every cent we earn from every book we sell in every format through every retailer is going to Medshare’s Ukraine fund.

And then there’s you.

Our newsletters and videologues are not only free, they will always be free. We also will never share your contact information with anyone. All we ask is that if you find one of our releases in any way useful, that you make a donation to Medshare. Over one third of Ukraine’s pre-war population has either been forced from their homes, kidnapped and shipped to Russia, or is trying to survive in occupied lands. This is our way to help who we can. Please, join us.

CLICK HERE TO SUPPORT MEDSHARE’S UKRAINE FUND

CLICK HERE TO SUPPORT MEDSHARE’S EFFORTS GLOBALLY

TRANSCIPT

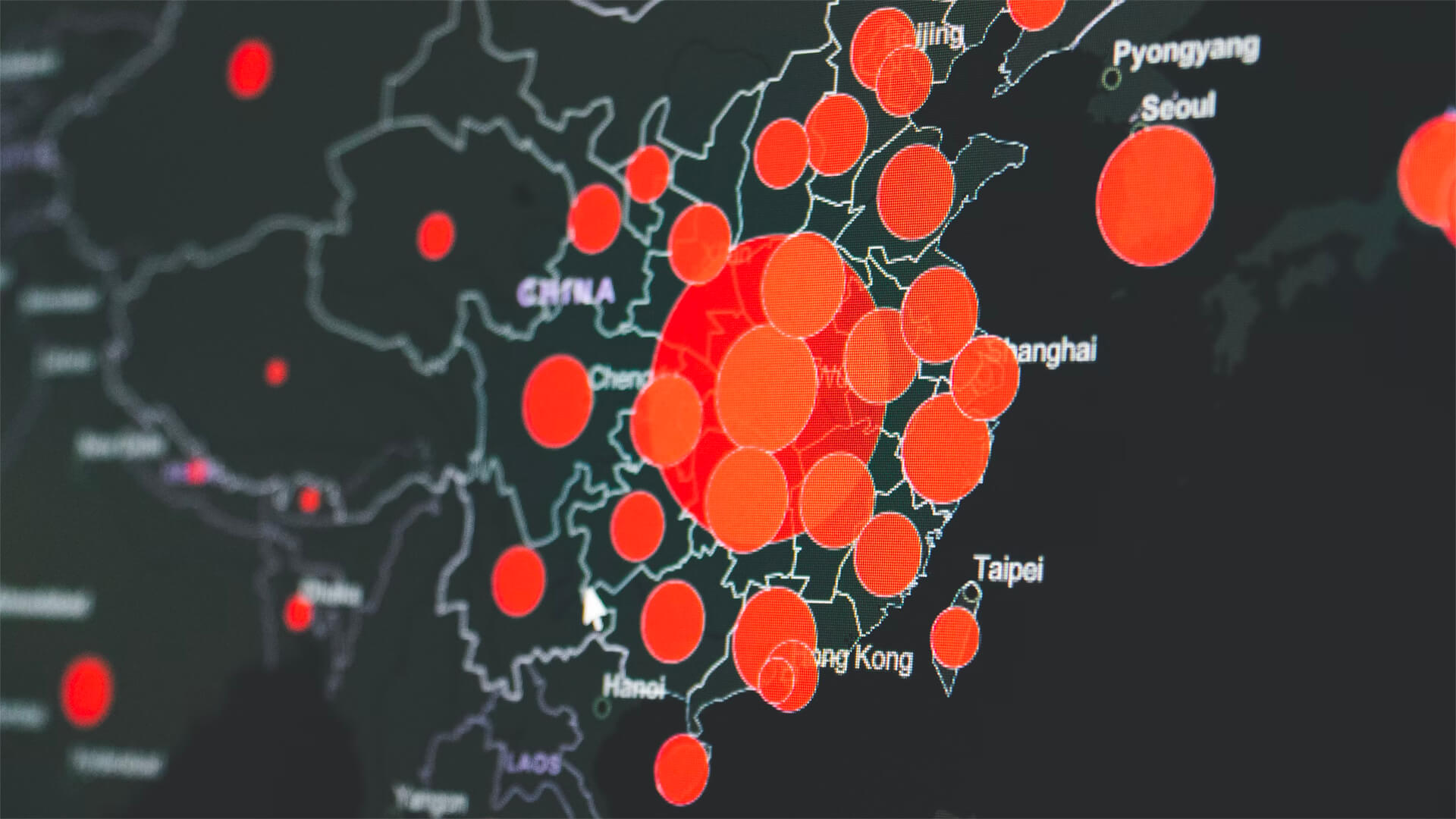

Hey Everybody. Peter Zeihan here coming at you from fairly windy and noisy Miami. I hope the sound on this one’s okay. The news that you can use this week is that the Chinese government is considering putting export bans on certain types of solar panel manufacturing, specifically the ability to make the wafers and silicon ingots that go into certain types of solar panels.

Some people are saying that this is a retaliation to things that the United States has done recently with semiconductors. But I don’t think there’s a direct link here. A couple of things. First of all, when you think of technology and you think of China, those two words only go together in the word manufacturing. The Chinese do not have a history and really any industry or subsector of being the innovators. They’ve got the manufacturing plant because it used a mix of labor and security and scale in order to become the dominant player in a lot of sectors…solar panels are one of those. But they don’t do much innovation at all. In fact, we were kind of racking our brains over this in the offices when what items out there were the Chinese the pioneers at, that they hold the technological edge, and there’s still a demand for it outside in the rest of the world. There is really nothing.

What’s going on here is that the Chinese have discovered that the United States is starting to build on an industrial policy and lots of other countries in the world are going with it. And once you marry state power to the efficiencies that you get from the American workforce and capital markets and market size, well, the Chinese just aren’t nearly as important in that sort of world.

So in those rare places where they do have a technical edge, they would like to keep it. This brings us to the solar panels. The Chinese dominated this space years ago and drove out most of the competition completely and then were left as the only ones in the space. Something like 80% of the global total and the assembly of solar panels requires a lot of fingers and eyes, something the Chinese dominate because of the size of the labor force. And that means they have made certain technological advances. The one that they’re talking about at the moment, the most important one by far, is that the Chinese and only the Chinese can make the wafers for the PV panels larger and thinner than anyone else. It’s an edge they would like to keep. But with the United States now mandating that a certain percentage or rising percentage of solar panels have to be manufactured in the United States. This technology is going to move there, whether it’s the U.S. having to develop it or not. So the question comes down to what kind of time frame are we talking about?

If the Americans started from a naked start, this would probably be a 5 to 8 year process, which for the Biden administration is just not fast enough. And so that brings us to the question of espionage. Now, the Americans, as a rule, are not great at industrial espionage, and it’s because our economy is too large and the government tends to be too hands off. So let’s say, for example, that the CIA did have the capacity to steal the plans for the next transmission that the Germans were able to put together. Who do you give it to? Ford? Chevy? Doesn’t work that way here because we would have to choose sides on everything. Our economy is too big. There just aren’t a lot of sectors where we only have one significant firm. But that’s not the case in most other systems where you have national champions, in part because of technology theft.

The three countries that would be most likely to go after this are three countries that after China are the biggest thieves of technology in the world, and that would be France, South Korea and Israel. And of those three, the South Koreans are definitely the ones to watch because they now have a fairly robust history of building industrial plants within the United States in order to meet whatever requirements the US government demands. So I can absolutely see a future where either the Biden administration breaks with longstanding policy and actually gets intelligence professionals involved in technology transfer against the wishes of the home country.

Or more likely, the South Koreans have already stolen stuff and they’re already negotiating with the Biden administration on how to build stuff on our side of the border in order to get the Koreans concessions and other economic sectors, which is something they would dearly love anyway.

One way or another, this is going to happen. The Biden administration has already put out the money. The demand is there. Solar panels are getting more efficient every year. They’re making more sense and more parts of the country. But most of all, most importantly, the political will for the general population to play hardball with the Chinese is there.

So all the pieces are in place and Chinese leadership in this sector, its days are numbered. And even if that proves to be false, if the Chinese refuse to export the tech to the United States, then the United States will have no choice but to build the stuff itself. One way or another solar panels are coming home.

Alright. That’s it for me. Take care, everyone.