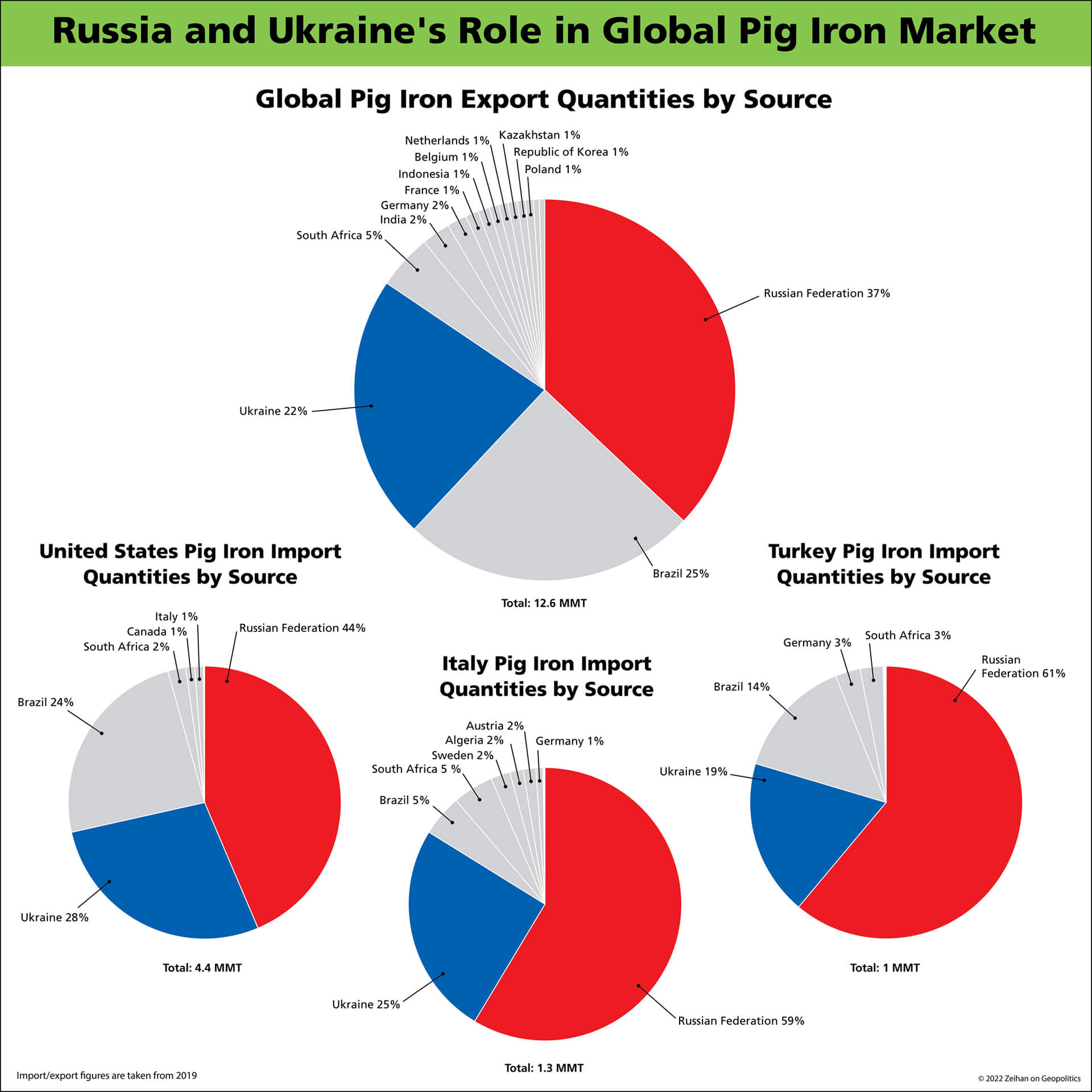

Steel is produced from iron ore, but to get from one to the other the ore must first be purified into pig iron (aka crude iron). Enter Russia and Ukraine, who source three-fifths of globally exported pig iron. Throw in Brazil and that fraction becomes four-fifths.

While most countries are heavily reliant on Russian and Ukrainian pig iron to feed their steel foundries, some will feel the effects of supply tightening worse than others. The United States receives over three million metric tons of pig iron from Russia and Ukraine, but also domestically produces over twenty million metric tons a year. Though it won’t be easy, we should be able to offset diminishing supply at least somewhat with increased production capacity. Weaker pig iron producing countries like Italy and Turkey, will have to find a new supplier. Quite a long trip from Brazil to the Mediterranean, assuming one can even find supplies to buy.

In the globalized economic system we live in (for now), the effects of even seemingly small supply disruptions ripple to everyone involved. As we witness the dissolution of this global network of trade (the main focus of my upcoming book, The End of the World is Just the Beginning, we can be sure to see multiple smaller-scale systems take its place. The challenge for the global economy moving forward is that Russia is a top five exporter of a wide array of industrial inputs—not just oil and gas, but iron, palladium, nickel, copper, silicon and more.

Join us on Tuesday, April 5 for our upcoming webinar, The Ukraine War: Industrial Materials Edition, where we’ll take a look at how supply disruptions out of Russia and Ukraine impact global supply chains with a particular focus on metals and minerals.

REGISTER FOR “THE UKRAINE WAR: INDUSTRIAL MATERIALS EDITION

Can’t make it to the live webinar? No problem! All paid registrants will be sent a link to access the recording of the webinar and Q&A session, as well as a copy of presentation materials, after the live webinar concludes.

Here at Zeihan On Geopolitics we select a single charity to sponsor. We have two criteria:

First, we look across the world and use our skill sets to identify where the needs are most acute. Second, we look for an institution with preexisting networks for both materials gathering and aid distribution. That way we know every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence. Then we give what we can.

Today, our chosen charity is a group called Medshare, which provides emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it. Until future notice, every cent we earn from every book we sell in every format through every retailer is going to Medshare’s Ukraine fund.

And then there’s you.

Our newsletters and videologues are not only free, they will always be free. We also will never share your contact information with anyone. All we ask is that if you find one of our releases in any way useful, that you make a donation to Medshare. Over one third of Ukraine’s pre-war population has either been forced from their homes, kidnapped and shipped to Russia, or is trying to survive in occupied lands. This is our way to help who we can. Please, join us.