The Russians had an oopsie with the launch pad at their main heavy-lift launch site following the launch of their Soyuz MS-28 spacecraft heading for the ISS. The unintended destruction of this launch pad cripples Russia’s space capabilities.

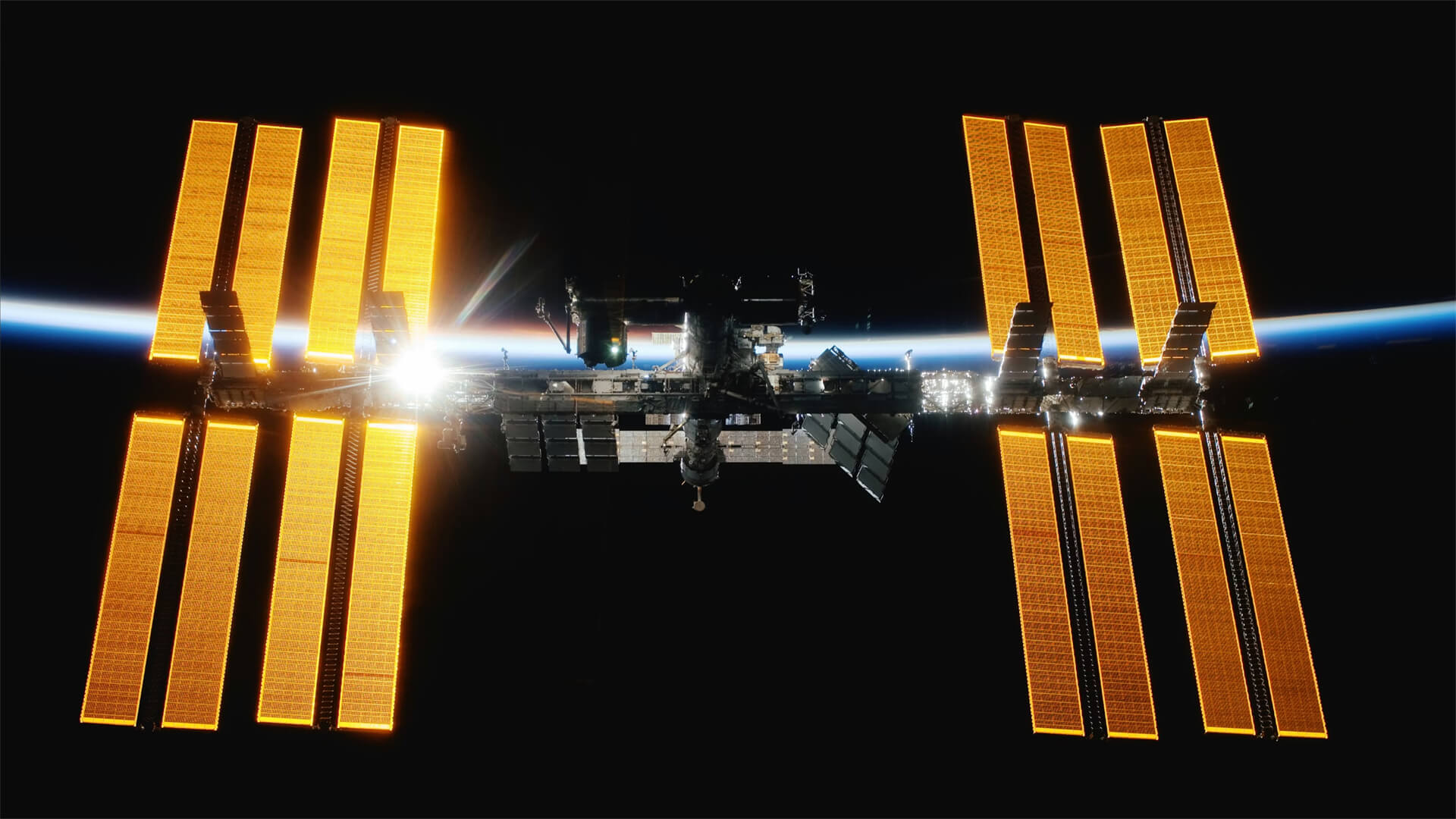

However, it’s not just Russia that will feel the heat from this. With the ISS slated for retirement within five years, the lack of Russian participation puts the future of the ISS…up in the air (excuse the pun). NASA isn’t ready to step in, and private sector plans for independent stations all require the ISS functional and in place.

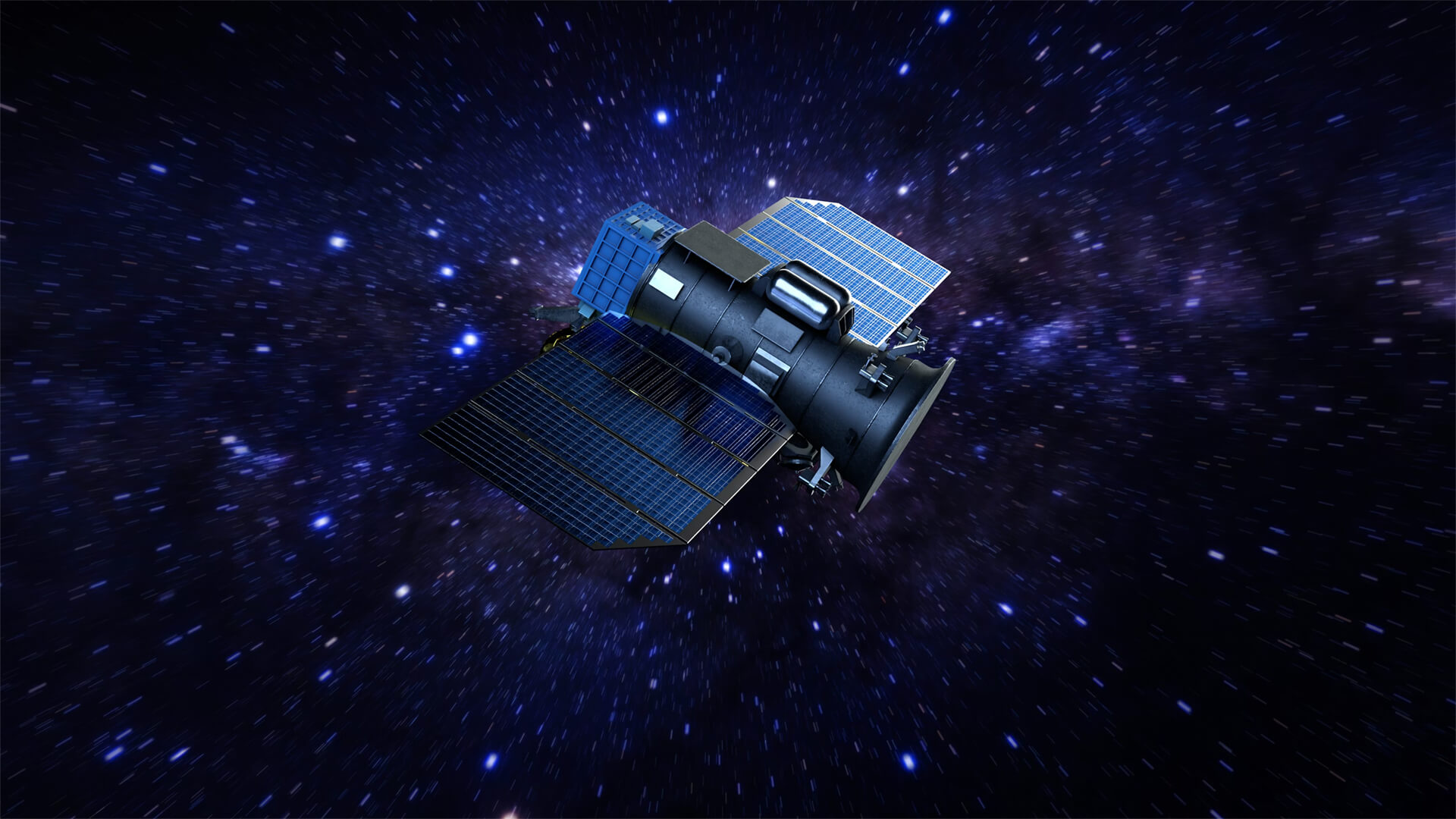

With the Russians unable to maintain a modern satellite network, coupled with their international isolation on the ground, what’s stopping them from sabotaging low-Earth orbit? It wouldn’t take much for them to trigger a Kessler Syndrome event. Not a great look for the future of space.

Transcript

Hello from chilly Colorado. It’s like four degrees here today. Peter Zeihan here, today. Well, last week during Thanksgiving, something blew up in the former Soviet Union. And it wasn’t in Ukraine. And it wasn’t in Russia. It was in Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan is the second largest of the former Soviet republics, kind of nestled under south central Russia.

What blew up was at the cosmodrome, which is where the Russians centered their space program during the Cold War, because you want your launch spot as close to the equator as possible. So the spin of the Earth helps you launch things. Anyway, the Kazakh Cosmodrome has been where everything has been happening, for the i.s.s., that really matters.

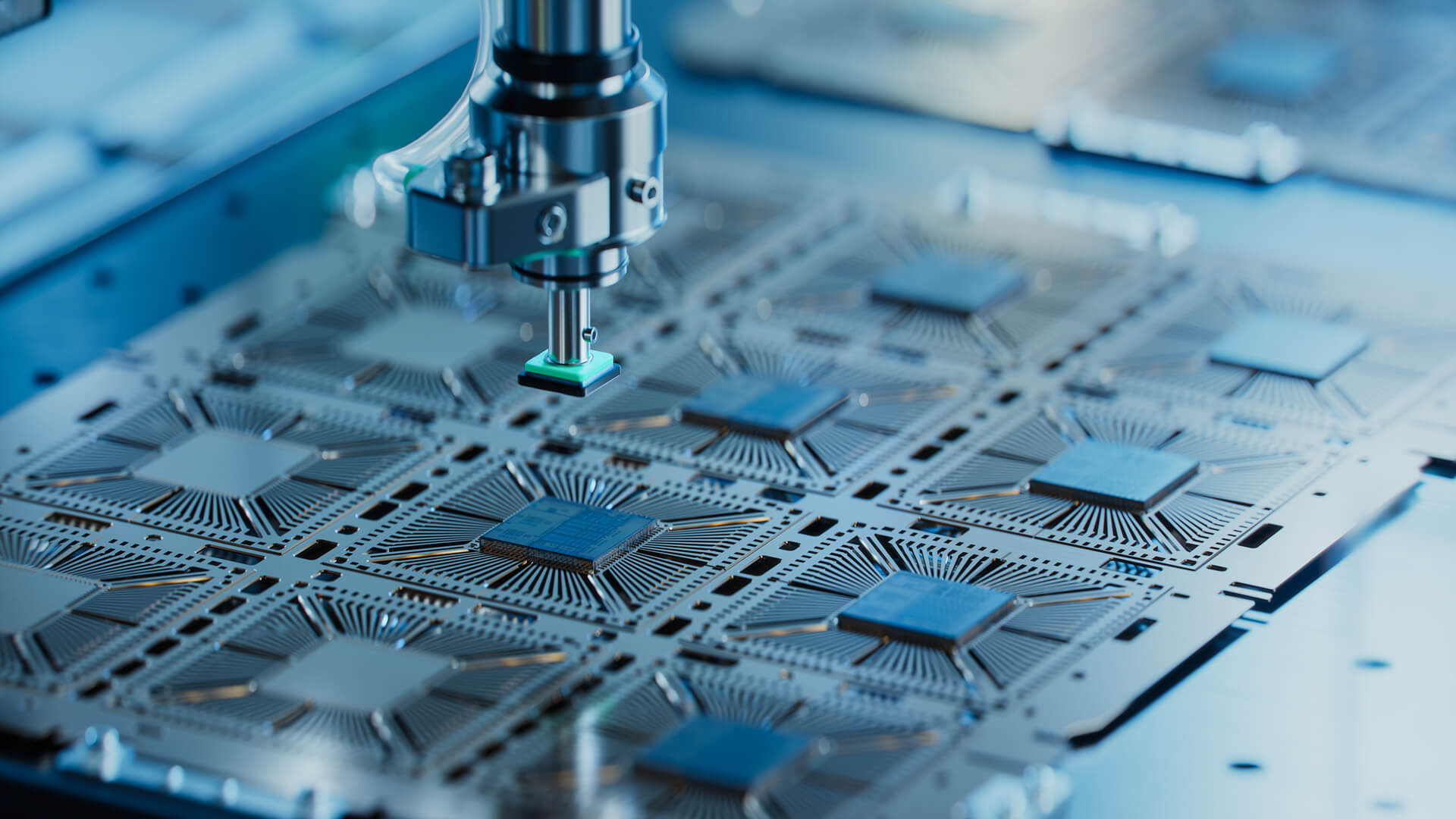

Most of the heavy lift is there. The U.S. does launch things first with a shuttle and now with, SpaceX’s Dragon capsules. But it’s the Soyuz that come out of Russia that really have the really heavy lift. Anyway, when they did a launch, the launch pad blew up and repairs are going to take a minimum of months, maybe years.

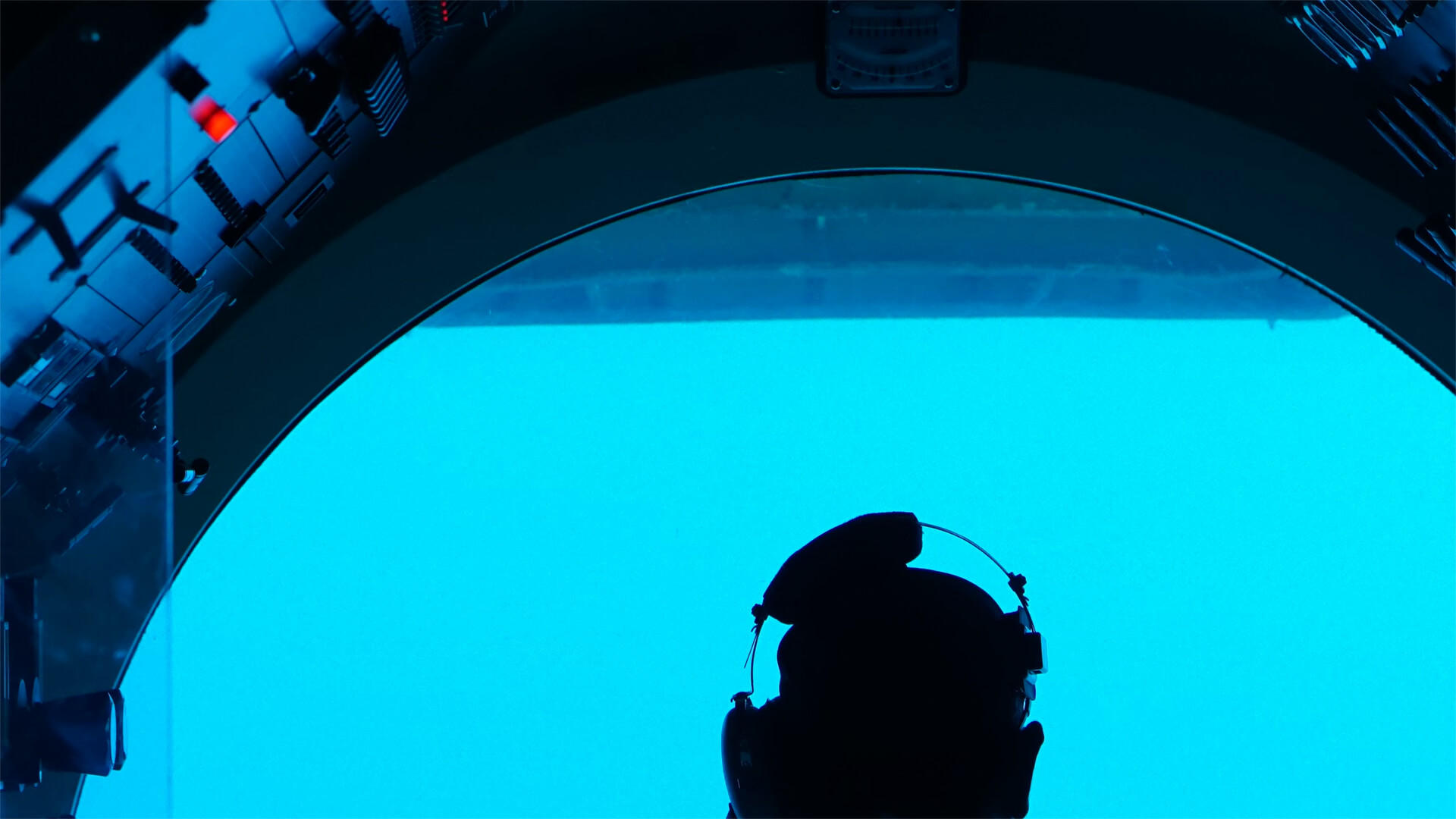

And this may be the beginning of the end of the ISS. That’s the International Space Station. Now, the ES was put up there as part of an American, Russian, post-Cold War, hey, we’re all friends now program back in the 1990s and has been the core of manned exploration ever since. However, it’s getting old and it was going to be retired within five years.

But now, without the heavy launch capacity, at least in the short term, probably longer. It’s unclear whether the Russians are going to continue to participate in the program at all.

It’s not the 1980s anymore. With Ukraine war three years ago, the Russians have become persona non grata in pretty much every aspect of international cooperation, even Eurovision, with the exception of the space program, because from the American point of view, without the Russians involved, it’s a question whether there would be a space program if all the certainly the ES itself is now in jeopardy, which means we have two problems.

First of all, without heavy lift capacity, it is questionable whether the ES can persist and there isn’t a replacement program in place right now. NASA has no no plans to put up a replacement system. And there’s a lot of science and a lot of work being done at the ES that really can’t be done anywhere else.

The plan is for private companies to go up and have their own satellite systems. It is unclear if anyone is ready for that, and everyone’s plans revolve around starting attached to the I.s.s. and then when the ISS is commissioned, moving off on their own, that plan may no longer be viable. And if we’re entering a period where there is no manned operations in space and things like satellite repair become really difficult, especially for the bigger ones, that’s problem.

One problem, too, is the Russians. The Russians of late have had a very. If I can’t have it, no one can have it, approach to really everything. Because the Soviet Union used to be a superpower. Until the Ukraine invasion, Russia was a major power. And now Japan, Korea, Taiwan, the United States and all the Europeans have basically shut the Russians out of everything they can.

They just don’t matter in international forums to the degree that they used to. And they certainly don’t have the cash to splash around to buy friends like they used to. So where does that leave them? Well, if the ISS fails and they can no longer have heavy space launch, then all of a sudden the Russians don’t have much need for satellites.

We did a video, a couple weeks back. We’ll share that on this one, where we talked about something called a Kessler syndrome. Basically, there are thousands, soon to be tens of thousands of satellites in low Earth orbit, and very few of them are Russian. The Russians can’t maintain what they have. So you got some old Cold War relics up.

There are a few things that have been launched since then, but for the most part, this is Starlink and to a lesser degree, American telecommunications. it doesn’t take a lot of imagination to think of how the Russians could disrupt that, because though they don’t have heavy space lift, anymore, they do still have space left.

They have their own cosmodrome in Russia proper, can’t get the huge volumes and the weights up, but it can certainly say go up and blow up a few satellites. And if you do that and you cause the, the shotgun effect of high velocity debris, Mach 25 it doesn’t require taking out too many satellites to cut a cascade reaction that basically makes low Earth orbit unusable for several years.

And the Russians are now in a position we’re considering that doing it on purpose, is probably crossing their radar now, because if they can’t use space in a meaningful way anymore and everyone else has taken their toys and go on home, then the Russians really don’t see the negative of making space unusable.