See Part 1: From Sears to Google and Part 2: From Order to Disorder… in America.

So here’s where I get a bit nervous. One of the great truths in geopolitics between 1950 and 2015 is that American domestic politics barely mattered at all. Support for the global Order was strongly bipartisan and it was considered treasonous for any politician to seek foreign support against a domestic opponent. Republicans may have not cared for JFK, but they certainly didn’t try to reach out to the Soviets during the Cuban Missile Crisis to undermine him. Democrats might demonize Nixon, but they never considered collaboration with the North Vietnamese to score political points at home. (Jane Fonda doesn’t count.) Even in periods of America’s most intense infighting, the strategy was the same: the Soviets were the bad guys, and global leadership via the Order was the way to fight them.

As such I get to dive into the political guts of every country in the world with regularity, but I don’t have to dissect the internal politics of my home country. That’s awesome! Americans are really touchy about their ideologies; the bipartisan nature of American Cold War foreign policy enabled geopolitical strategists like me to take a pass on all things political.

Well, so much for that.

With American foreign policy in a state of collapse right along with America’s party structures, I now need to apply the tools I use daily on the United Kingdom and Germany and Russia and Brazil and China and Vietnam and India and Iran to the United States.

Everybody buckle up.

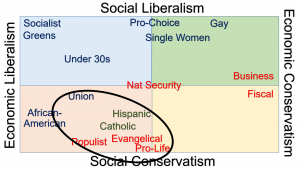

Take a look at this matrix. It breaks out the various voting blocks in the United States on ideology as well as old-style party affiliation. The closer to the top, the more you feel the government should stay out of your personal life. The closer to the right, the more you believe the government has no business in your economic life. If you hug the left, you feel the government must take an active role in managing the economy. If you’re near the bottom, you want the government to not simply respect but actively protect traditional societal norms. If you’re near a corner, you have hybrid views. For example, if you find yourself at the intersection of economic and social conservatism (the bottom right), you believe the government has no role in helping poor people get food, and the stress of poverty will actually do them spiritual good. If you’re completely opposite where economic and social liberalism meet (the top left) you look forward to the day that we all sing kumbaya dressed in government issued gunny-sacks paid for by the confiscation of the assets of anyone who owns their own home.

While you’re digesting that, a couple caveats followed by a simple observation:

Caveat #1: These are broad, poorly-defined groups because that’s how coalitions (and graphic making) work.

Caveat #2: Predicting the tactical shifts in American politics is tricky. Americans tend to be a bit moody. What follows is less a hard forecast and instead a probable outcome based on what we know today. It’s an example of the sort of work that’s consuming bigger and bigger slices of my time.

The observation: There are a lot of American factions in the bottom-left quadrant. Folks who are socially conservative on cultural issues, but also feel the government should play a role in ironing out economic inequalities – or at least personally give them more stuff.

That concentration is where Donald Trump is focusing his attention. The oval is the cluster of factions Trump is fashioning into a new coalition. Those bottom three categories (populists, evangelicals and pro-lifers) are his core. But that trio is not far off from the ideological mix that tends to drive unions, Catholics and Hispanics. I’m not asserting here that Trump has these groups in the bag. That’d be hilarious. I’m simply noting the ideologies of Trump’s core groups are not all that far off from these other groups, and that voting patterns among these factions in the 2016 election indicated a sharp break with what we thought we knew about who votes blue versus red.

Most union members, for example, are conservative on social issues and most of Trump’s core is left-of-center on economic issues. All tend to be somewhat distrustful of globalism. Despite all the rhetoric on all sides, the Hispanic vote isn’t locked into the Democratic coalition. Most voting Hispanics are social conservatives who are broadly against large-scale immigration unless it deals with family reunification issues. If Trump’s core coalition could find a way to massage the race issue, there’s a distinct and mind-bending possibility that not only could the – let’s call them Trumplicans – capture a large chunk of the Hispanic vote, but a sizable piece of the ideologically-similar African-American vote as well. That would easily give the Trumplican coalition an outright majority of American voters.

Noticeably absent from the Trumplican coalition are a pair of factions core to the traditional Republican identity: fiscal conservatives and the business community. Both are dismissed by Trump’s core as either irrelevant or an enemy, and both hold – at best – a very weak hand in the Trump administration at present. Their core ideological issue is that math matters – let’s call them Mathocrats – and they strongly favor a right-leaning tax policy that minimizes the role of government. Since the Trumplicans are somewhat left on economics, particularly when it comes to government spending, this pair of formerly Republican factions are likely to from the nucleus of opposition to the Trumplicans.

So who are the Mathocrats’ potential allies? Greens, Socialists and youth voters are probably out of the question as rebelling against basic mathematics is sorta their thing. That leaves a trio of more economically moderate groups near the top-center of the ideological matrix: pro-Choice voters, single women and gays. Women and gays are concerned with political rights, something that modern business thinks is broadly peachy. Women and gays want to protect their own property and financial assets – you haven’t seen a hissy fit until you tell a 35-year-old gay man that his partner can’t be listed on a lending agreement. (I sure know I threw one.) Such economic concerns are near and dear to the hearts of both fiscal conservatives and the business community. The only tension in such an alliance is getting over inertial expectations – and since issues of race are not in play, a Mathocrat coalition would have a far easier time of putting the past to bed than a Trumplican coalition.

Now think about this in terms of foreign policy.

Under the Order, the all-or-nothing nature of the Cold War dictated that foreign policy had to be bipartisan. It was not overly shaped by either party, nor did it much vary from administration to administration regardless. But now there is no unifying threat or need or theme. Each new party can have a foreign policy that makes sense to its constituents as things evolve. American foreign policy is likely to oscillate not only between administrations, but within them.

That is likely to be far more erratic than it sounds. Think of what has happened in the past two years. The Americans have abandoned many of their alliances and geopolitical agreements and yet taken minimal hits – NAFTA, NATO, the WTO, deals with Cuba and Iran and Turkey and both Koreas. It is all falling apart, yet the U.S. economy is growing quickly. Instead of being abuzz with talk of the world burning these past two weeks, Americans instead obsessed about how a would-be Supreme Court justice acted in high school. Foreign policy – at best – demands third-tier attention in the American mind, and typically then only when it is mated to a domestic issue they care more about.

But look who is missing from both potential coalitions: national security voters. Folks who care about national security are the ultimate agnostics. They don’t care about social mores or the culture war or tax rates or development policy or the balance of power between the federal center and the states. So long as the military is capable and politically protected, they’re good. American isolation from the world will make American foreign policy a part-time issue. America’s likely future political parties will make American foreign policy inconsistent. And with America’s military supporters being the ultimate swing voters, American foreign policy will be intensely kinetic.

Yes, the Americans are taking a break from the world and that is problematic, but it is nothing compared to what is coming. In about a decade, instead of living in a world where the Americans are the most powerful force for global stability, they are likely to be the most powerful force for global instability.