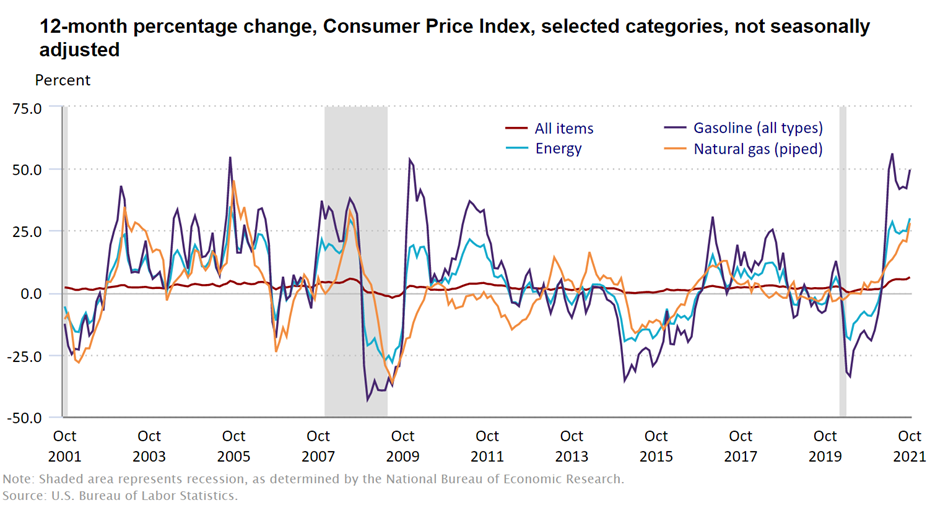

On November 18 news leaked out of Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, China and India that the Americans have approached pretty much every country that matters about a joint, simultaneous release of oil from each country that maintains emergency reserves. The goal being to tamp down rising oil prices. The subtext is that the Biden administration’s efforts to get OPEC and its oil-exporting partners to produce more crude have proven unsuccessful.

Normally, I’d just dismiss this as media banter and rumor mongering. Stuff like this drops out of the ether every time oil prices rise. This time is probably different; Simultaneous indications from multiple countries that lack a track record of energy-related drama suggests the news is for real.

I guess the primary reason I would have normally dismissed the idea of oil releases is because…it is a really, really stupid idea.

First off, oil demand is inelastic. When prices go up or down by 10%, 20%, 50% it is rare for demand to budge at all. Only when prices go up (or down) by an extreme amount and stay there for months do we get fundamental shifts to demand. Which means any short-term price drop won’t impact the underlying market fundamentals one whit.

Second, even if every country on the planet with oil sitting in tanks or salt caverns agreed to follow Biden’s lead, they could not maintain the effort for nearly long enough to shift the demand picture. Most countries don’t have more than two months of import cover. Turns out that most find storing something like crude oil — a material that’s corrosive and toxic — to be difficult and expensive.

Third, what makes oil prices go down isn’t so much increases in flow but increases in production and above all storage. It is having extra oil on hand that weakens prices. Releasing crude from storage isn’t production. Releasing crude from storage reduces storage. It actually makes the market tighter.

Which means, fourth, as soon any releases end, demand fundamentals will not simply take prices right back to where they were, they will take prices higher because there is now less storage as a buffer.

And so, reserves are not tapped lightly. Historically speaking, the United States has only released oil from its reserves to impact pricing when there has been an actual production disruption. For example, in 1991 when Iraq invaded Kuwait, or in 2005 when Iraq descended into civil war and Venezuela got serious about its journey to self-destruction. Nothing like that is happening currently.

These aren’t particularly sophisticated economic talking points. “Oil 201” if you will. And that is what has me concerned. Transport Secretary Pete Buttigieg knows this. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm knows this. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo knows this. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan knows this. The chances of this quartet of the smartest people on TeamBiden not advising the president of such a basic economic function are zero.

Which tells me that one of two things has happened.

Option1: There’s some sort of massive misunderstanding going on here and the information that’s leaking out of Asia is in some way wrong. If so, this’ll blow over very quickly and we’ll all go back to our lives.

Option2: Biden’s instinctive populism has overwhelmed his willingness to listen to basic facts, and he is pursuing a populist, Trumpesque economic policy in the belief that his diktats can direct the markets.

If it is Option2 then, well, crap. If the goal is to decrease oil prices, there’s an easier, faster, diplomatically cheaper, more economically viable and more environmentally friendly way to do it: The United States is the world’s largest oil producer because of the shale revolution. Using a mix of new production techniques developed in the past two decades, U.S. oil producers can bring new production to market in just six weeks. Even Saudi Arabia’s reserve capacity takes a minimum of three months to bring on-line. Shale output has far lower carbon output as part of its production than the global average, and because U.S. shale is produced in the United States rather than a different hemisphere, the shipping footprint is similarly lower. (Also, production taxes!) Politically, it would indeed be awkward for green-friendly Biden to approach the U.S. oil sector about producing more oil, but IMO not nearly as awkward as it has been for him to approach de facto Saudi Arabian leader Muhammad “Hacksaw” bin Salman…which he has already done. (Only to be turned down flat.)

I have been nursing some concerns about the Biden administration’s economic policies for some time. I’ve reserved judgement because most of his plans require Congressional action, and until Congress actually passes something of substance it is all just political theater. The oil-release action is in a different category because it can be done by executive order.

As a rule, I like to give presidents plenty of time before I declare them lost causes, and therefore part of the problem rather than part of the solution. With Obama it took until year five, with the specific straw being when Obama started barring people who brought him news he ideologically disagreed with from even entering the Oval Office. That action turned the entire Executive Branch into a tone-deaf echo chamber. With Trump it happened in year three when he decided he was “done” with coronavirus. That action is largely responsible for the death of a half million Americans. After seeing the quality of the people in Biden’s cabinet, it never occurred to me that it might happen before year two.

But here we may be. Arguing that Option2 is what is truly in play, is another energy-related action from Biden administration this week: an order that the Federal Trade Commission investigate American oil producers, refiners and gasoline distributors for price fixing. Fixing in the wildly unconcentrated American oil complex is functionally impossible. Leaving aside the hundreds of differently motivated oil producers and hundreds of regionalized gasoline distributors and tens of thousands of gasoline retailers, there are 135 operating oil refineries in the United States, and they tend towards cutthroat competition. Collusion among them would be hilariously unwieldy and only one tattletale hold-out would result in billions in fines for the other 134. Biden should know this too. Buttigieg and Granholm and Raimondo and Sullivan certainly do. This isn’t policymaking. This is populist blamestorming in the Trumpian style, using the tools of the state to target your political opponents.

But I digress.

What’s happening with the oil markets, what is driving prices higher, what is apparently prompting Biden to push for a mass release, are symptoms of an issue far larger and more substantive than mere presidential mismanagement. What’s happening is financial mismanagement on a global scale. Its effects are magnifying with time and will be with us long after Biden is gone. What we are seeing now, with oil prices well on their way to $90 a barrel, is just the tip of the iceberg.

But it will not be felt everywhere.

Interested in more? Energy inflation — deep, chronic, and above all varied — is a big piece of the broader, long-term inflation picture that we’ll be exploring in our final seminar on the evolutions in the American and global economies in the age of deglobalization. Join us December 1 for Part III: The Face of Inflation.

REGISTER FOR PART III: THE FACE OF INFLATION

Scheduling conflicts? Not to worry. Everyone who registers will be provided with a recording of the webinar to watch at their leisure.

We hope you will also join us today the Supply Chains No More webinar and Q&A session. Registration information and more at the link below.

Part II: Supply Chains No More

Today, November 19, 1p Eastern

REGISTER FOR SUPPLY CHAINS NO MORE

Those who missed out on Part I: Wither the Workforce can purchase access to the recorded webinar and presentation materials at the link below.

PURCHASE RECORDING OF PART I: WITHER THE WORKFORCE