Financial sanctions; diplomatic isolation; peer pressure – these are the tools the West is using to convince the Putin government that it should abandon its “Ukraine adventure.”

They are the wrong tools for the wrong job. The Russians are not in the Crimea and Eastern Ukraine to boost Putin’s popularity at home or out of a fit of pique that Ukraine had a revolution. Russian power is in motion as part of the first stage of an extended effort to secure the Russian homeland. Moscow will continue until the European Union and NATO either form an unbreakable wall of opposition or crumble.

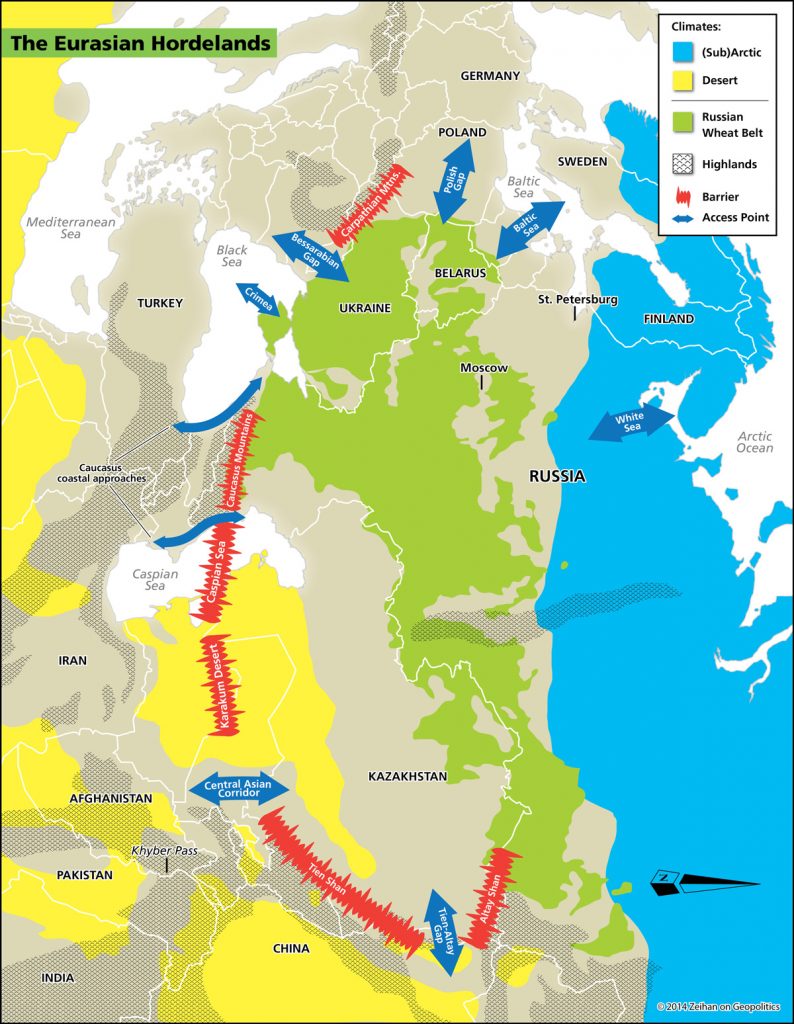

Russian territory is part of an endless flatland unparalleled in the world. The open portions of the Eurasian steppe are nearly as large as the entirety of the US Lower-48. Web-working infrastructure across its arid plains proved so expensive that even the strategic-minded, price-insensitive Soviets sharply circumscribed their efforts. Even today, only one road and two rail corridors venture east of the Urals to lay claim to Siberia. Russia is a place where only a manpower-heavy military capable of swarming over vast tracks of land can rule effectively. Let’s call it the Hordelands.

Key to ruling the Hordelands is the ability to limit outsiders from entering them; once they do, any defender becomes locked in a war of mobility and attrition. The trick is to reinforce all nine of the lands’ access points: the Tien-Altay Gap, the Central Asian Corridor, the two Caucasus coastal approaches, the Crimea, the Bessarabian Gap, the Polish Gap, the Baltic coast and the White Sea coast. Failure transforms the Hordelands into a bloody buffet. The Soviet Union once controlled all nine. The day the Soviet Empire fell in 1992, those holdings were reduced to two. With Russia’s reacquiring of the Crimea in February, Moscow now is up to three.

That explains why, but not why now? The Russian resurgence began almost fifteen years ago, shortly after which Russia rationalized its finances and debt. As early as 2006, high energy prices granted the Kremlin more cash than it could spend. Russia proved it could implement complex and sustained intelligence and military operations as early as 2008. Why now, in 2014, is Moscow finally moving?

Simply put, it is running out of people.

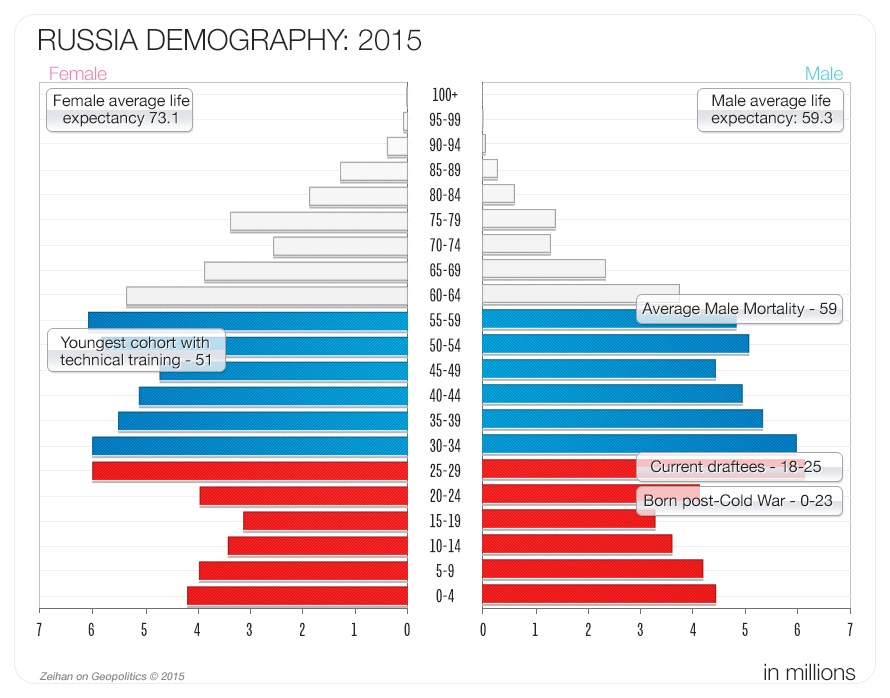

Immediately after the Cold War’s end, the bottom fell out of the Russian birth rate, gutting the lower ranks of the Russian population structure. A quarter of a century later, there are more 50-somethings than teenagers. In five short years, those teenagers will prove inadequate to fill the Red Army’s ranks. If Russia is to use that army to re-anchor the Hordelands’ access points, it needs to do so while it has enough soldiers.

Instead, a would-be engineer must first apprentice with an established engineer for several years. Technical training in Russia collapsed before the Soviet fall, and now the youngest cadre of engineers who have the full suite of technical skills has entered their 50s. In chauvinist Russia, nearly all are men, and according to the last non-politicized data that escaped the Federal State Statistics Service, male mortality is only 59. Maintaining the Russian system — which includes everything from the national rail network to the natural gas fields to Moscow’s steam tunnels to the Red Army to the nuclear missile forces — for a territory as expansive as the Hordelands requires a huge skilled labor pool that Russia simply no longer has. In a few short years, Russia will degrade from having a very small and expensive skilled labor pool to not having one at all, forcing the Russians to choose which bits of their system to not maintain.

If the re-anchoring is not achieved soon, Russia will lose the ability to even try, which would condemn it to wither from within. While the overall Russian demography is failing, the damage is almost wholly concentrated among ethnic Russians. There are many minorities — largely Muslim minorities such as the Tatars and the Chechens — whose demographics are as young, healthy and growing as the Russians are aging, sick and shrinking. Adding Ukrainians and more to the mix will certainly make managing Russia’s “internal” issues more complicated, but intimidating minorities into compliance is a bit of a national pastime. Russia has been doing it — and doing it with frightening effectiveness — so long as there has been a Russia. Maintaining control over such diverse groups in a country with secure external borders is feasible. Doing it with exposed borders is not.

And so the Russians are coming. Coming for Crimea, and Donetsk and Torez and Luhansk and Slovyansk and Odessa. And not just for Ukraine, but for Georgia and Armenia and Azerbaijan and Moldova and Belarus. And when that is done Romania and Estonia and Lithuania and Latvia and Poland. In an era when there enough Russians to man Russia, Moscow thinks of the independence of all of these places as a disturbing academic exercise. In an era where Russia is running out of Russians, the independence of all of these places is a mortal threat. The Russians will not stop until either they re-anchor or are made to stop, and there currently simply isn’t a recognition in Europe that this has already gotten very real.

Which brings us to two outcomes: one financial, one strategic.

Financially, the Russians have far more room to maneuver than most think. They have $1 trillion saved in various funds — one of the upsides of a demography that is dying young is that retirement funds can be used for other things — and can survive any sanctions the West can throw at them. The Russians also are making a gambit for survival, and if pushed willing to walk away from everything – partnerships with ExxonMobil, debt payments, shipments of nickel, even long-term natural gas sales. Russia is happy to continue to sell the world its wares — and certainly prefers to — but if a choice is forced between Russia’s expansion to defensible borders and a few hundred billion in annual economic gains, bet on gritty austerity rather than capitulation to sanctions.

Strategically, three of the Hordelands’ access points — Bessarabia, Poland and the Baltic — will require the Russians challenging EU and NATO members. Aside from a few hundred troops rotating through NATO’s border states, there currently is no indication that any EU or NATO country is taking the Russian advance seriously. Moreover, the European countries — and this includes the five NATO/EU members that face the direct threat — have had 25 years to wean themselves off of Russian energy, but have instead moved in the opposite direction. Their strategic policy is to rely on Russia to keep the lights on, and to rely on America to protect them from Russia. The result of those (in)actions is a painfully uncomfortable question: will the Americans bleed for those who have proven unwilling to raise anything but the pitch of their voices in their own defense?

Those curious can find the answer to that question and the world that unfolds in its aftermath in The Accidental Superpower, available November 4, 2014.