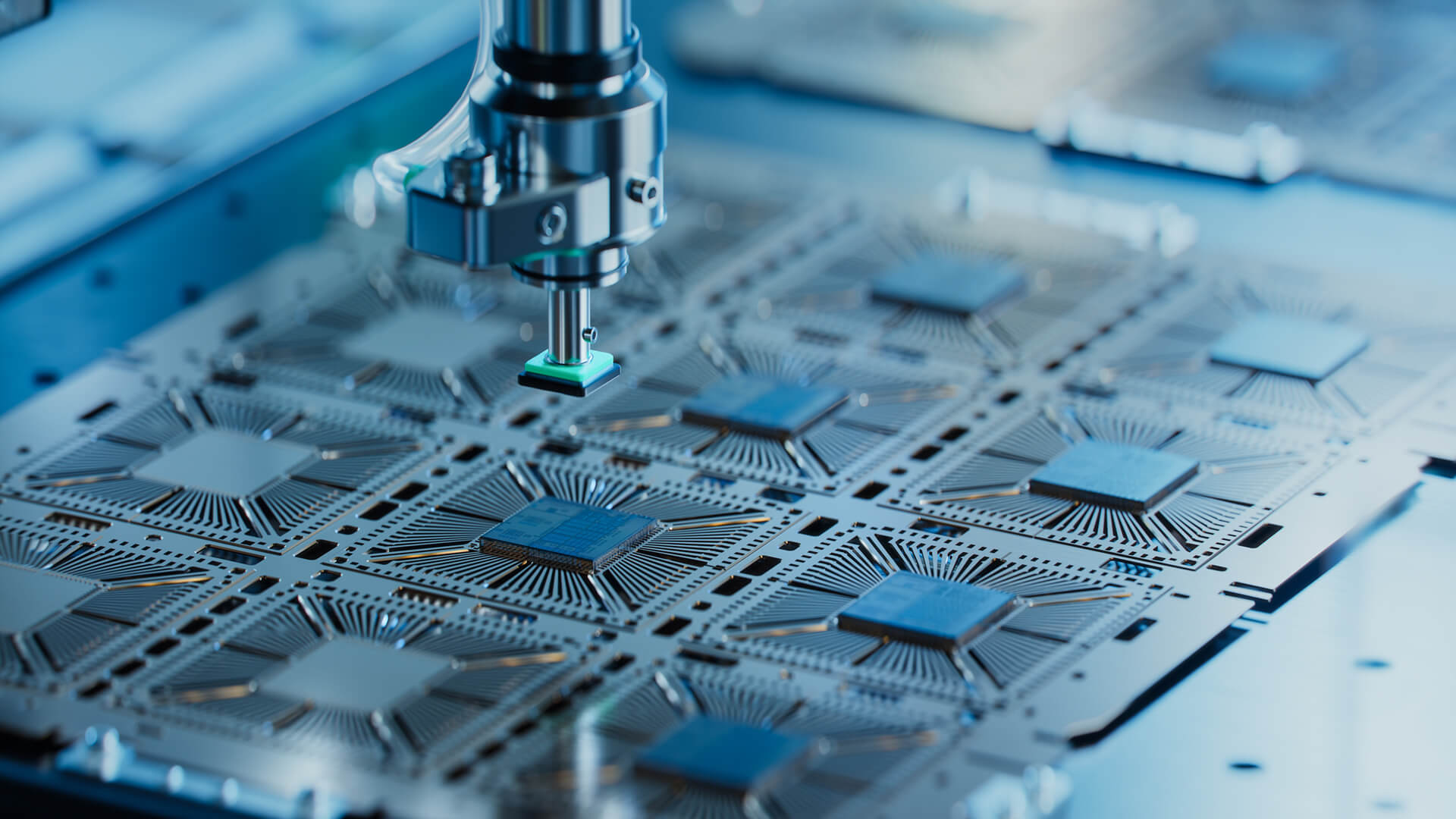

The semiconductor industry is one of ever-growing importance and its leaders—Intel and TSMC—are now fighting to be the first to bring the next generation of advanced chips to market.

Since its founding in the late 60s, Intel has been on the leading-edge of semiconductor manufacturing. For decades it pushed new technologies forward, vastly influencing technology developments across myriad sectors. Intel’s reign of supremacy ended, however, when in 2016 it misjudged the readiness of a novel lithography technology—extreme ultra-violet (EUV).

When Intel hesitated, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) took the EUV plunge, and it paid off. TSMC is now the leading producer of sub-7nm chips, having utilized EUV lithography technology on a mass scale since 2019. Intel, on the other hand, just reached that point last year. Intel is hungry though, and has ambitious plans for the near-future, including securing the next generation of lithography machines (high-NA EUV) before any of its competitors.

The importance of the semiconductor industry will continue to grow as technology evolves and the green transition is carried out. Adding additional layers of security, stability, and cushion to the manufacturing process will be essential as geopolitical tensions rise and the world deglobalizes.

Here at Zeihan On Geopolitics we select a single charity to sponsor. We have two criteria:

First, we look across the world and use our skill sets to identify where the needs are most acute. Second, we look for an institution with preexisting networks for both materials gathering and aid distribution. That way we know every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence. Then we give what we can.

Today, our chosen charity is a group called Medshare, which provides emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it. Until future notice, every cent we earn from every book we sell in every format through every retailer is going to Medshare’s Ukraine fund.

And then there’s you.

Our newsletters and videologues are not only free, they will always be free. We also will never share your contact information with anyone. All we ask is that if you find one of our releases in any way useful, that you make a donation to Medshare. Over one third of Ukraine’s pre-war population has either been forced from their homes, kidnapped and shipped to Russia, or is trying to survive in occupied lands. This is our way to help who we can. Please, join us.

TranscripT

Good morning from a frigid Colorado. It’s a balmy zero degrees this morning. And today, I want to tell you a tale of three companies and the state of the semiconductor industry from a technological and production point of view. Now, if you go back to the world before 2017, the technology of the day was something called deep ultraviolet, which was basically a way of producing microchips and intel.

The American technological giant was the world leader by pretty much any measure, and they had gotten a little cocky and they’d gotten a little bit lazy. So they would design chips two or three or four models out, but would only produce the next one up because they were so far ahead of everybody else. They didn’t feel the need to jump steps.

So they would use the EUV and they would make a chip that was marginally better than the one before. And then at the end of the year, no one was had caught up. So they do it again and again and again. And they do this for like 15 years. I mean, they’re very good at what they do, but they could have pushed the technological envelope a lot more if had they chosen to.

In part, that was because of the nature of the technology. The problem with it is you have to kind of make micro adjustments and physically adjust the equipment for each type of chip. And you have to do that manually and physically. And so with every design, you had to do it all over and with every machine in a fabrication facility, you would have to do it independently.

So no new chips from different machines are going to be quite exactly alike. And it generated a relatively higher loss rate from the final semiconductors than what we have today. And so generated a little bit more waste. But again, they were the industry leader. No one was close. Well, they were always had their eye on the future, however.

And so they invested in new technologies that would take them beyond the EUV, one of which is EUV, extreme ultraviolet. And the company that developed that technology is ASML out of the Netherlands. And back in 2016, ASML thought the stuff was ready to go. So they’re providing demonstrations for Intel, showing them how this technology is better. You can not only get more nodes on a chip and get to smaller and smaller nanometers, but it’s all digital.

So you kind of type in what you want to the machine over the course of a few days to a few weeks, and then the machine doesn’t actually have to be physically manipulated in the way that DV did. Now what that would mean is you’d have a higher success rate and more efficiency. But back in 2016, Intel was like, I don’t think this technology is quite right and we’re the industry leader.

We’re going to give it a few more years. Well, ASML not very happy with that. Marketed the technology to everybody else and a company decided to take the plunge. That company is TSMC out of Taiwan. And when we get to 2017, TSMC suddenly hits the ball out of the park and proves that EUV is ready for mass application and over the next couple of years very rapidly overtakes Intel because they have a shorter turnaround time for their chips and they can make chips with smaller nanometer sections.

It isn’t until 2022 or 2023 that Intel finally makes its first extreme ultraviolet chips. So TSMC in Taiwan has been the industry leader now for several years now. We’ve had a kind of a reverse in the roles. Now ASML, the Dutch have another another new technology called high numerical aperture, whose physics I’m not even to pretend to understand.

And they have marketed again. And this time Intel is the one that’s behind. And they’re kind of desperate and kind of hungry. And TSMC is the one that’s resting on their laurels. So the first delivery of those new machines, the high end chips, went to Intel in the second week of January of this year. And Intel expects two things.

Number one, they plan to overtake TSMC using the EUV technology in 2024, hoping to get down to two nanometers. Right now, the industry lead is at about three nanometers and that’s a TSMC product. And then next year they hope to leapfrog even further, provided that these new high end machines work, which will, you know, we’ll find out pretty soon.

Anyway. That’s where we are right now. In terms of the overall geopolitics, it’s pretty straightforward. Right now, 90% of all I hand chips are made by one company, TSMC, in one city in Taiwan, it’s a high concentration. But if Intel working with ASML can pull this off, all of a sudden we will have facilities in the United States that are working on the higher end stuff with some of the first facilities that are going be going online outside of Phenix and Columbus, Ohio.

So stay tuned because the geography of these chips is about to evolve pretty significantly if high works. And if not, we’re still stuck with Taiwan, it could be worse.