Much of current media coverage of the corona virus is focusing on the issue of variants of SARS-COV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Here in the United States, we’re currently in a race against time in our attempts to vaccinate the population and significantly slow—or stop—transmission before one of the nastier variants hits our shores.

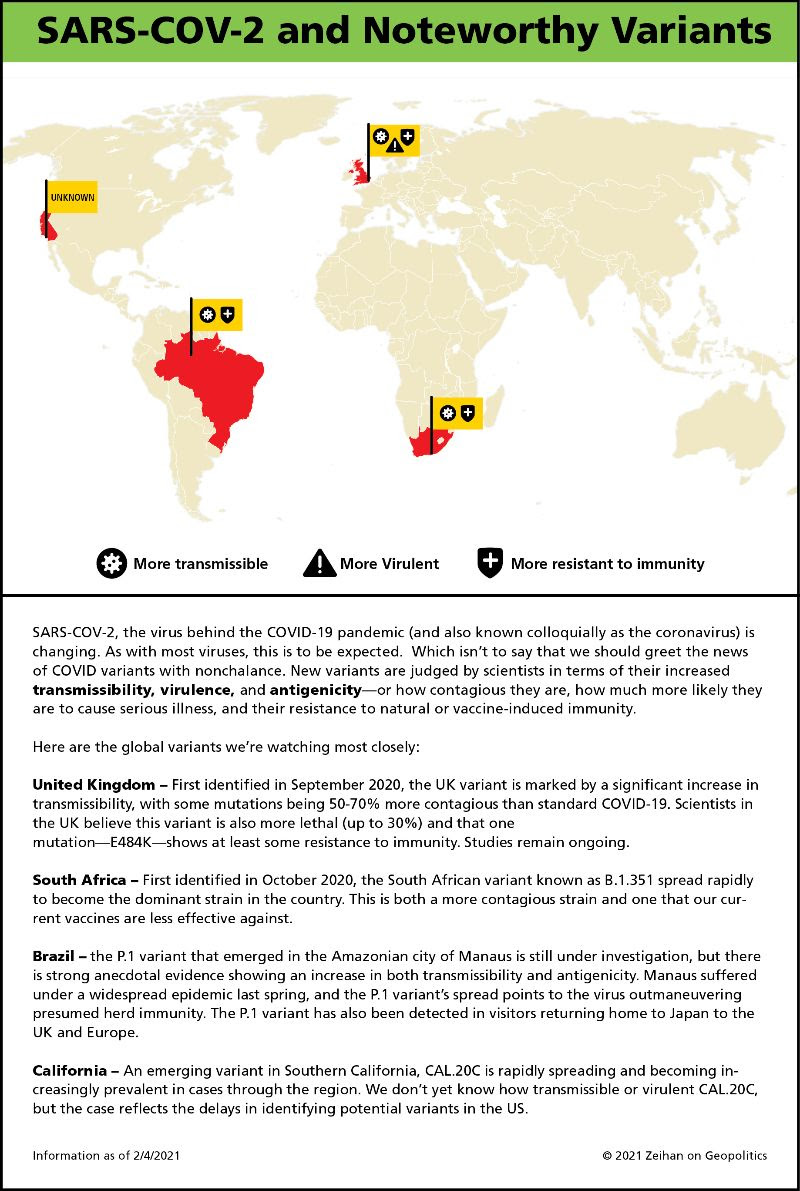

Variants are mutations of a virus that changes how the virus interacts with our bodies. Chances are most of us have seen illustrations of the corona virus by now—a ball covered in spikey appendages. The protein spikes are how the corona virus attaches itself to our cells, and where our immune system attaches itself to the virus. In the UK and likely South Africa and Brazil, the local variants have mutations making the virus not only easier to attach to our cells (and making it more infectious), but also harder for our immune systems to combat (making it more resistant to vaccines and natural immunity). In the UK, there is evidence that their particular variant is deadlier, too.

What we know about the UK variant, and what we still don’t understand about variants in Brazil, South Africa, and California boils down to genomic sequencing. The UK has invested heavily in recent months into expanding their already better-than-most genomic sequencing and tracking of viral variants. They’ve put in the yeoman’s work of tracking changes to SARS-COV-2’s protein spike exterior and how changes in these proteins impact our relationship to the virus.

In the rest of the world, the tracking and identification of variants has been hampered by the lack of rigorous, coordinated international sampling and sequencing—an effort such as the US might have spearheaded in the past—and the lack of robust testing in the US itself. Some states are improving sampling and genomic sequencing efforts on their own, such as California, which announced that a local variant was spreading rapidly in January 2021. Anecdotal evidence is starting to come in, but as of this writing we still do not know the full extent of what the California variant will mean for regional populations.