My partner just got back from a grocery store stock-up. The trip-in has been part of our weekly ritual since this coronavirus thing got going. The post-shopping conversation has a similar ritualistic feel. Whoever stays home queries the other one with the same barrage. Here’s this week’s Q&A:

How busy was it? (Packed)

People wearing masks? (Maybe two-thirds?)

Bare shelves? (Nope)

Produce? (Loads) *thumbs up*

Plenty of flour? (Yup)

What about pasta? (Only if you’re gluten free) *mutual gag*

Meat products? (Everything but hotdogs and the cheap sausages)

Anything on our list not there? (No caramel-flavored coffee creamer)

We’ll come back to that creamer.

Much of my work involves me balancing on the knife’s edge between big-picture statements and projections on one side, and an endless litany of caveats and clarifications on the other. About half of what I speak and/or write about really really big stuff: the fate of nations over timeframes measured in decades.

I love doing the big stuff. Sussing out the big trends in technology and geography and demographics to play forward a global game of multidimensional chess with dozens, even thousands, of players.

But to do the big stuff you absolutely must sweat the details. Every snowflake is a potential avalanche trigger. It wasn’t so long ago that America’s shale revolution fell firmly into the “small stuff” category. Now it’s altered the global trajectory. I (heavily) rely upon Melissa Taylor and Michael Nayebi-Oskoui to alert me to just those sort of avalanche triggers.

Which makes discussing America’s food supply in the time of coronavirus somewhat…messy. As I am wont to do, let’s start with the big.

Despite all the disruption the coronavirus epidemic is causing the United States, the food supply system is working well. Disruptions are largely limited to changes in demand (such as hoarding), as opposed to challenges to supply. There is zero reason to expect the United States to need to bar food exports. No region of the country is going to starve, much less the country as a whole.

My high confidence in this projection comes down to simple economic geography. America’s agricultural capacity is absolutely unparalleled.

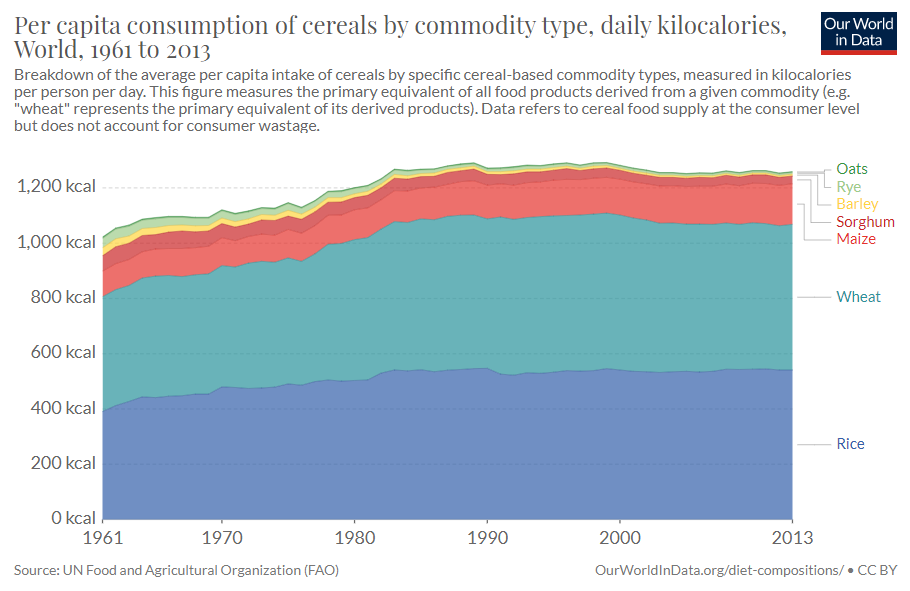

Vast tracts of flat, fertile, arable land in a wide variety of temperate climate subzones to support a wealth of crops. Winter weather to kill bugs and weeds. Wind currents from the Pacific and Gulf of Mexico to provide ample, reliable precipitation. And all of it overlaid with the world’s largest, interconnected, naturally navigable waterway system to ensure easy and cheap transport of the resulting product. Toss in the vast petroleum production of the American shale revolution—oil is the base material used to fabricate the core agricultural inputs of gasoline, diesel fuel, fertilizer, herbicide, pesticide and fungicide—and every part of the American seasonal agricultural supply chain is domestic, redundant, inexpensive and secure.

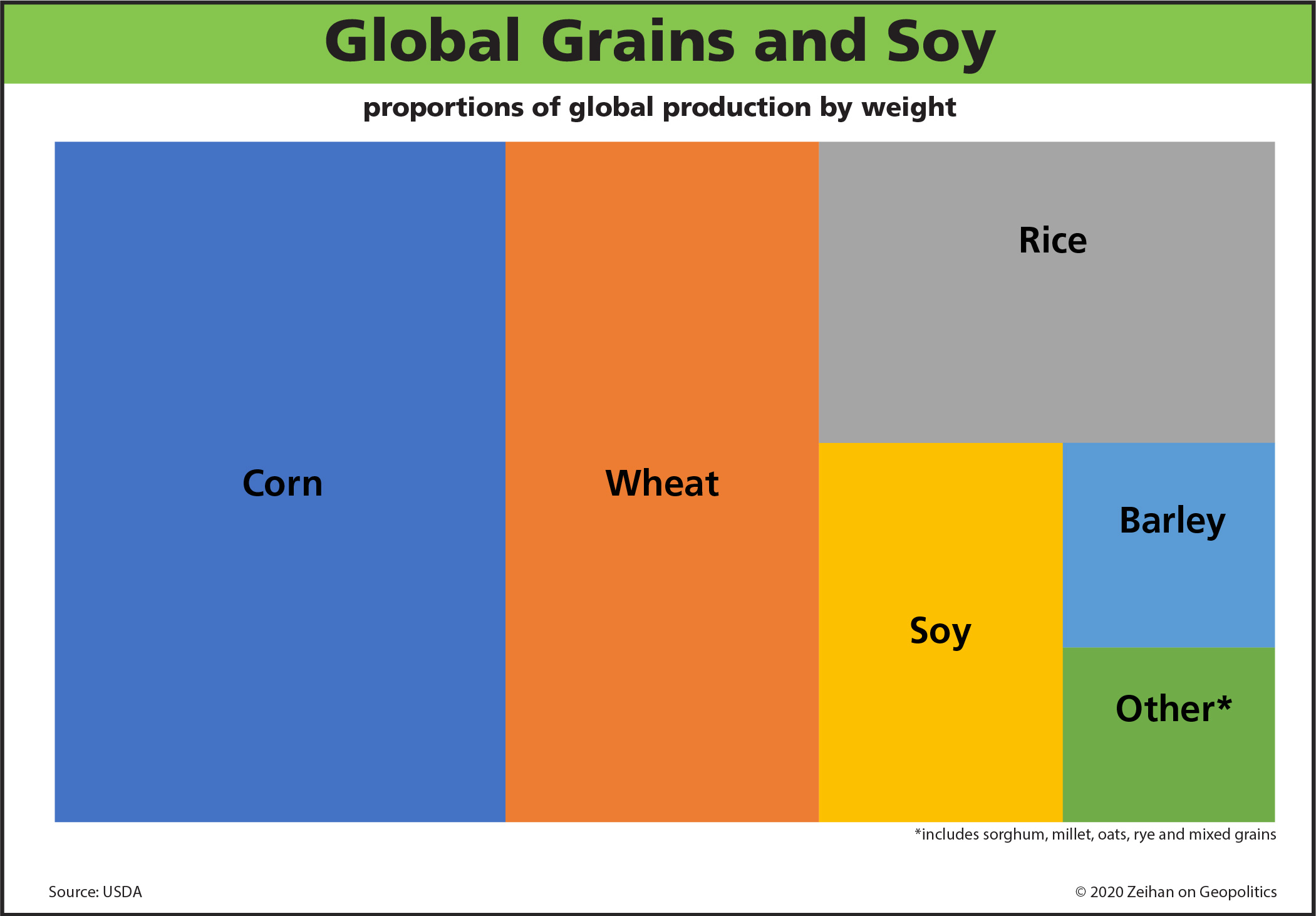

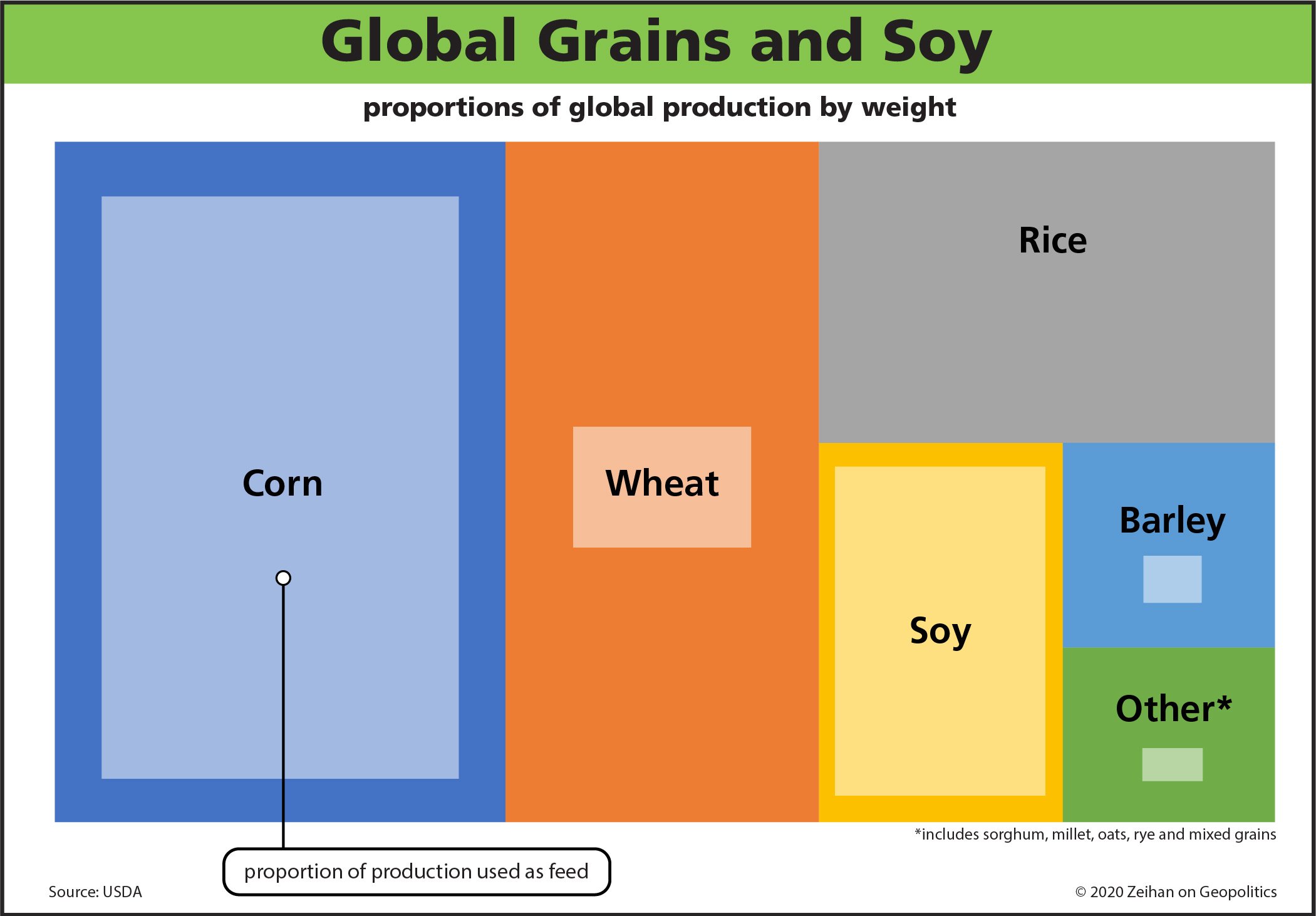

It shows in the output. The United States is either the largest or among the largest producers of corn and wheat and soy and oats and dairy and beef and pork and chicken and apples and you get the idea. All-in the American agricultural industry is so productive and outsized for its population it must export about one out of every four calories it produces. There are exceedingly few items the United States is not self-sufficient in, and even those items—such as, God-forbid, coffee—are nearly all easily-sourced at volume within the Western Hemisphere.

The nature of most agricultural production is also pretty damn near virus resistant. Most aspects of the farming/ranching process deal with few people over large chunks of territory. Whether it is sowing or fertilizer crops in a large piece of farm equipment, or zipping around a cattle herd on an ATV, there simply isn’t much opportunity for contamination. Even with more constrained facilities such as dairies or chicken farms, it’s the animals rather than the humans that cannot social distance. So, big picture, the issue simply isn’t going to be one of insufficient calories being produced.

Which is where Melissa and Michael both intervene and say, “not so fast”.

Much of the country’s agricultural labor force in the harvesting of fruits and vegetables, as well as in the processing of meats, is not highly spaced out and so is vulnerable to the virus. Each step of getting foodstuffs from production to processing to packaging to retail requires a different truck…with a different driver. More steps, more chances for disruption. And food producers in one part of the country might not even be aware of food demands in a different part of the country, leading them to plow under their fields or dump milk in ditches, even in times of stress.

As regards American food security at the moment, the detail-oriented minds of Melissa and Michael are somewhere between thoughtful concern and a slight edge of quiet panic. The big picture guy in me blithely waves a hand at the complexity while noting extreme redundancy, extreme resilience, extreme slack in the system, and extreme overproduction compared to national demand. Soooo many things would need to go wrong for the United States to face meaningful shortages. They note that many areas in Texas are already experiencing scarcities of flour and steaks and chicken and produce – and that in a state that produces all these things, in many cases through multiple seasons. I note that we’re in pretty good shape in Colorado, even though the concept of growing food at high altitude, in the winter no less, is simply laughable.

(Incidentally, our best guess for that last disconnect is that Texans are used to being scared more, and so are more experienced hoarders. A Texas hurricane can take basic infrastructure offline for weeks, prompting locals to panic shop for everything imaginable. The Houston area is still recovering from Hurricane Harvey. In contrast, Colorado snowstorms don’t require much more than grabbing a couple extra frozen pizzas. We got a foot of snow here Sunday and Monday, yet by Tuesday morning everything was already clear.)

The core of our dispute is information. The United States still hasn’t reached sustainable COVID testing capacity of 150,000 people a day. Until the country hits one million, complete economic lockdown is really the only mitigation method for any flareups. At the rate we are going we will not get there this year. That leaves all three of us guessing. Just how bad COVID-19 is going to be? Just how long will it last? Can we get reinfected? How soon until a reasonable treatment?

Which brings us to two conclusions.

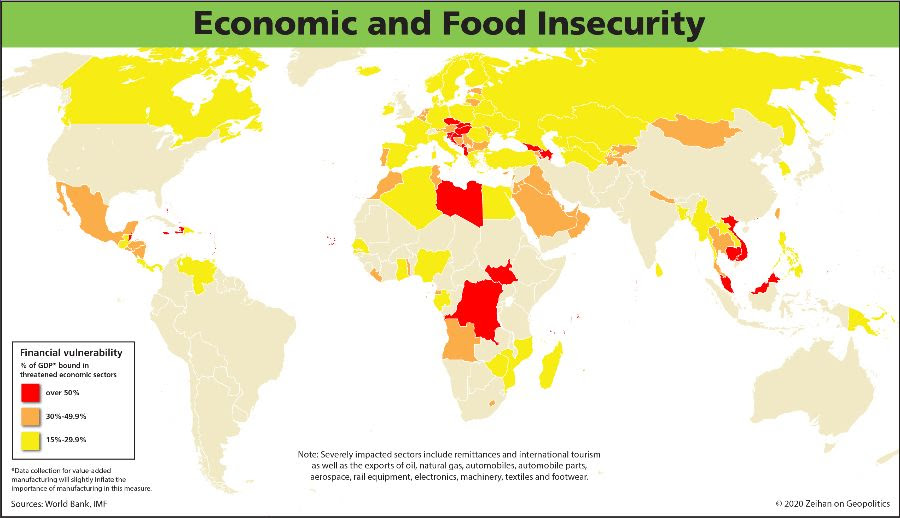

First, it is time to start gaming out weaknesses in the system. Trucking, meat packing, food processing, migrant labor dependency, grocery store workers. All these and more are potential failure points. For them to impact—I mean really impact—food supplies at the local level they would need to fail badly. But low risk is not the same as no risk, and coronavirus continues to…surprise.

Second, we will have product mismatches. It is less an issue of raw demand or supply, and instead an issue of preparation and packaging.

Consider toilet paper. Are people hording it? Yes (damn them), but there is more going on here. Since as many people as possible are working from home, most…use of the “facilities” is also occurring at home. Ergo, most everyone needs more toilet paper at home. The two-ply rolls of fluffy TP you buy for your bathroom are not the same as those giant wheels of ultra-thin near-newsprint you typically suffer through at work. While technically they are substitutes for one another, the two products use different wood fiber, they are made in different production runs, and they are packaged and distributed differently. The country’s overall supply of TP hasn’t changed. Neither has its demand. But the product mix has shifted.

The same thing will occur—is occurring—with food. Something like one-third of the meals Americans used to eat were eaten out. The sort of food processing and packaging for IHOP is significantly different from the sorts of products you purchase at the grocery store. The food processing industry is shifting onto a new footing more appropriate for Quarantine World, but it doesn’t happen overnight. In the meantime, it isn’t that there is less food available, it is our new stay-at-home lifestyles have concentrated demand into specific product categories.

There’s also more than a bit of second-guessing. Grocery stores are bracing for disruption in the food supply chain. While that may never actually occur, they feel obligated to provide for everyone’s basic needs regardless of everyone’s less-than-basic preferences—doubly so while the food processing industry is shifting gears. So, for weeks they have been making changes to what they order and warehouse, not based on customer preference, but instead with an eye towards nutrition and redundancy. More big bottles of canola oil from North Dakota, fewer small bottles of committed-suicide-in-the-wild collected-by-singing-cherubim imported hazelnut oil. More half-and-half, less…luxuriously velvety delectable caramel coffee creamer.

That’s what product mismatches means. Not that we’re out of food, but that there’s a hole in grocery shelves where you wish there was a very specific kind of food. Unless COVID disrupts the system far more than it has to date, the big-picture guy in me can confidently proclaim that this isn’t about shortages, but instead about insurance.

Or at least it isn’t about shortages yet. As Melissa and Michael relentlessly pointed out to me as I was assembling this piece, at the moment due to coronavirus-triggered facility shutdowns, some 10% of America’s beef and pork processing is offline. I’ll admit that one made me a little nervous.

Next week it is my turn to make the grocery run. If there is no bacon I will very suddenly shift from the big-picture guy to someone far more focused on the details.

But I won’t starve while doing it.

If you have more questions about the resiliency of the US Agricultural supply system in the face of pressures due to COVID-19, join Zeihan on Geopolitics’ Peter Zeihan for an in-depth seminar on April 20, 2020.

REGISTER HERE

Future planned invents include:

- Transport and Supply Chains

- Manufacturing

- Industrial Commodities