Let’s start with the headline good news. Since our last update on April 19, it appears the COVID-19 epidemic may have plateaued in the United States with direct COVID-caused deaths peaking on April 21 at just under 2700 cases.

Of course, there are a boatload of caveats:

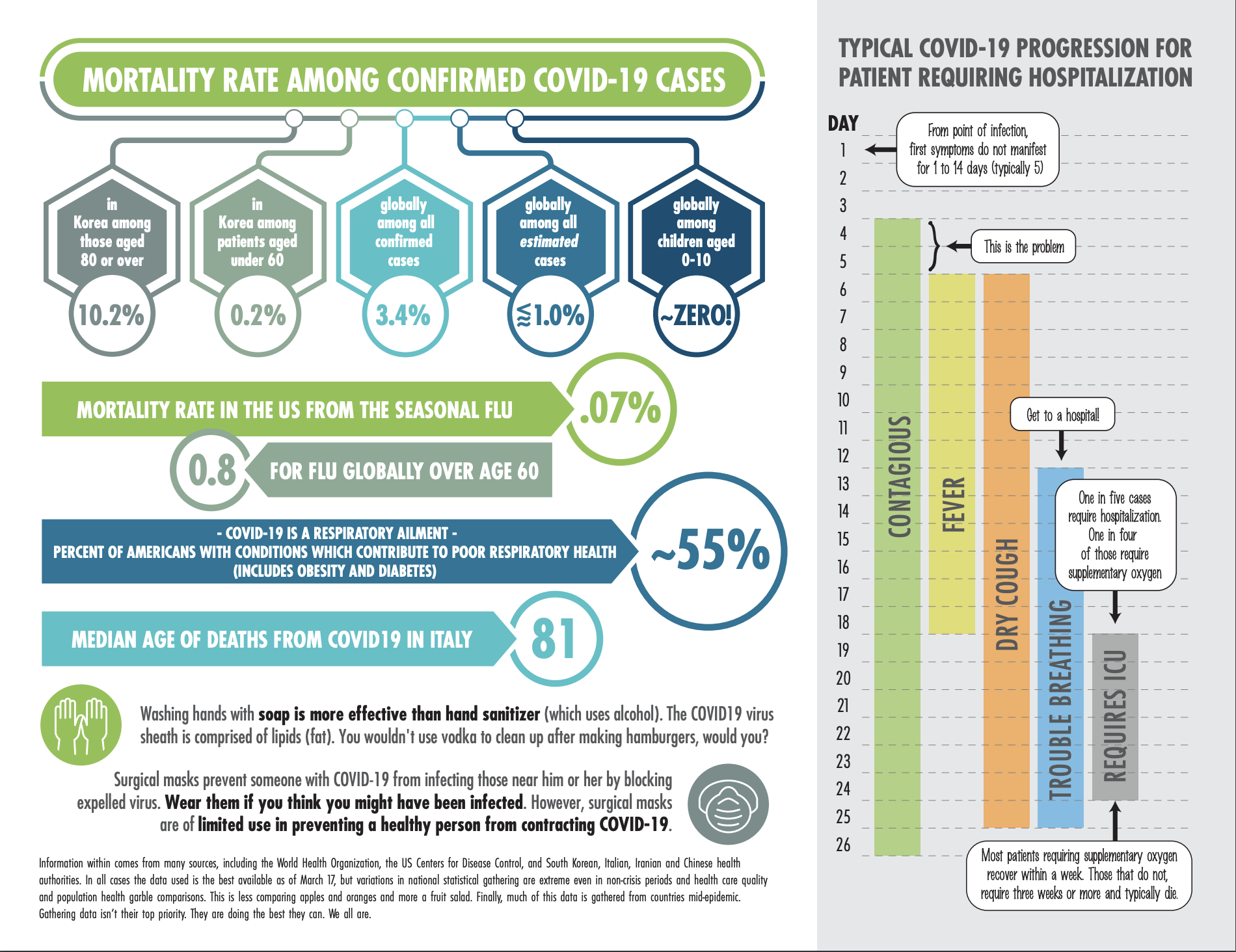

- While COVID-attributed deaths are falling, the number of confirmed cases is higher than ever. This could mean deaths are about to pick up again (which would be bad). Or, it could mean we are detecting more cases even though the actual number of cases has already peaked (which would be great). Or, this might simply be yet another trough-peak disconnect as we have seen before (which would be…frustrating). We really don’t know, and the only way to know is to do more testing. A lot more testing.

- Speaking of which, the US is still nowhere near where it needs to be for testing levels if the goal is to avoid secondary epidemics. We really need at least one million daily tests, with those tests generating results within an hour or two. Without such testing in place contact tracing is impossible, which means the only means of combatting additional epidemics would be additional shutdowns.

- There is nothing within the data at present that is what we could call “clean”. There is no single set of data gathering guidelines among the states, or even within individual states. This is pretty typical of the United States in general; most data is collected not at the national level, but by the states. And it is especially true during an emergency when the emphasis is on saving lives as opposed to making sure spreadsheets line up.

- Just because national death figures have stabilized and are falling doesn’t mean such is occurring everywhere. Different cities and states were exposed to COVID at different times, and different demographic patterns shape the epidemic in different ways. Densely populated New York may well be through the worst *fingers crossed*, but my far more rural home state of Iowa is clearly nowhere near its own peak.

Take the example of my hometown of Marshalltown. The local hospital (which lacks ICU capacity) fears it is about to be Italy-style overwhelmed. The hospital takes cases from throughout central Iowa – a region which includes the now-closed meatpacking plant in nearby Tama, as well as Marshalltown’s own (which remains open). In beef and pork meatpacking, social distancing at work is more or less impossible. Such facilities rank right up there with cruise ships and jails for COVID intensity. Cases linked to Marshalltown’s meatpacking facility are responsible for most of the fear at the hospital. I have yet to hear anyone use the word “triage” but I worry it is coming.

But even here the case data reflects not only differences in statistical management, but in the nature of anti-coronavirus policies at the state and local levels.

Compare Iowa’s experience to that of our arch-nemesis, Minnesota.

Minnesota has about half-again the population of Iowa, and as one might expect, total testing in Minnesota is about half-again the total testing level of Iowa. But that is where the similarity between the hardworking, morally upstanding people of Iowa and the turgid pile of frigid confusion that is Minnesota ends.

Despite its smaller population, Iowa has half-again more COVID-19 cases than Minnesota. I’ve little doubt that this is due to Iowa still having no stay-at-home orders from the governor as well as the fact that Iowa hosts the country’s densest cluster of meatpacking facilities.

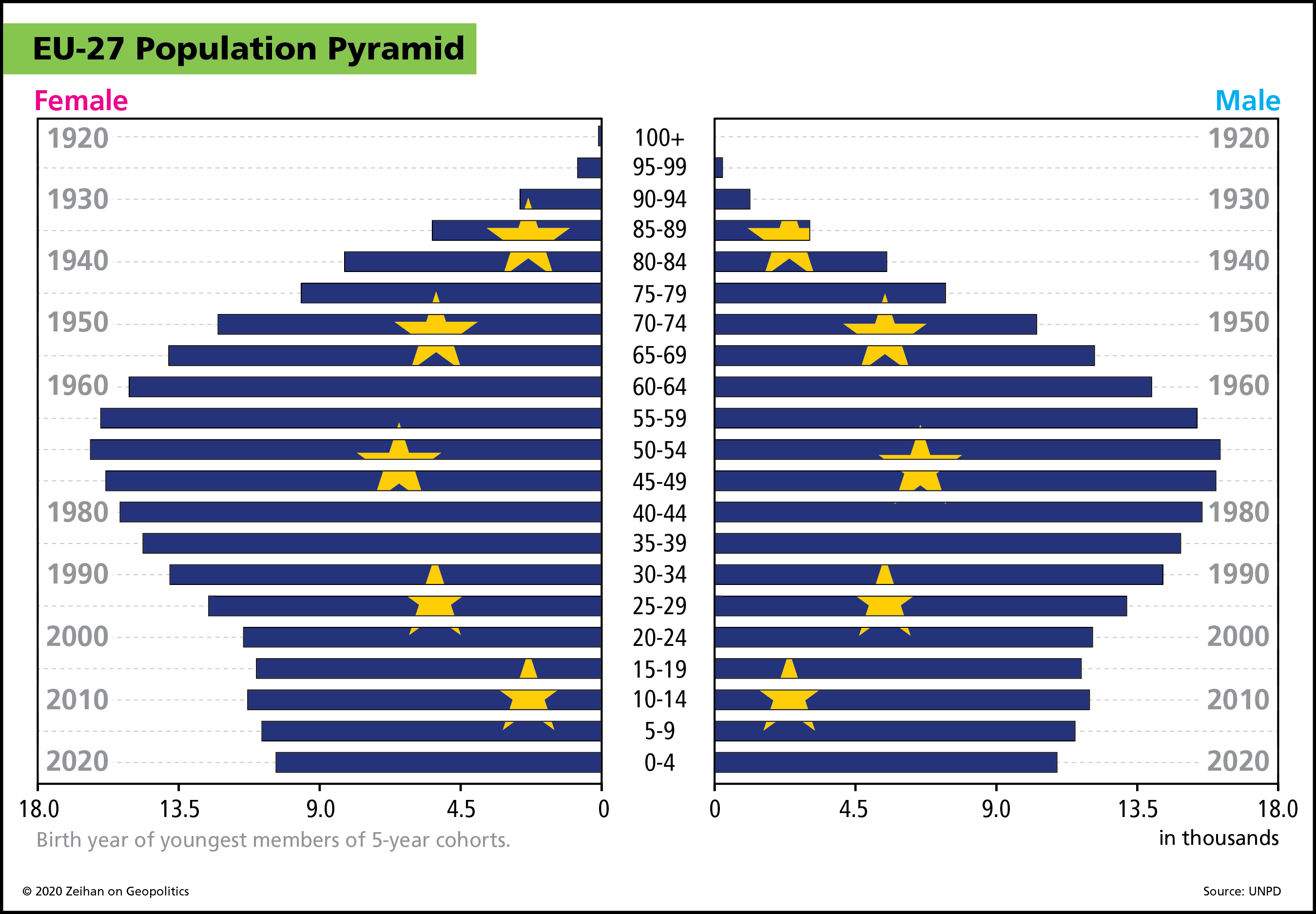

But despite Iowa’s much larger overall caseload, the state has also suffered fewer than half the deaths from COVID as Minnesota. Over ¾ of Iowa’s positive cases are in people aged 65 and younger, an age group that is highly likely to survive the virus. Minnesota’s cases are skewed into older age groups, making death more likely.

Bottom line? For a country of the size and diversity and complexity of the United States, there is no single road forward to reopening. Nor to secondary epidemics. Nor to aftereffects. We cannot project New York’s experience onto anyone. And we certainly don’t want to project Minnesota’s.

A Note From Peter

If you enjoy our newsletters, please consider showing your appreciation through a donation to Feeding America if you are able to do so. One of the biggest problems the country faces at present is food dislocation: pre-COVID, nearly 40% of all foods were not consumed at home. Instead they were destined for places like restaurants and college dorms. Shifting the supply chain to grocery stores takes time and money, but people need food now. Some 23 million students used to be on school lunches, for example. That servicing has evaporated. Feeding America helps bridge the gap between America’s food supply (which remains robust) and its demand (which coronavirus has shifted faster than the supply chains can keep up).

A little goes a very long way. For a single dollar, FA can feed one person for three days.

Join Peter Zeihan and Melissa Taylor April 30th for an in-depth discussion and presentation on the impact of COVID-19 on global agricultural production and the stability of the world’s food supply.

Future planned invents include:

- Transport and Supply Chains

- Manufacturing

- Industrial Commodities