Read the other installments in this series:

Life after Trump, Part I: Living in the Lightning

Life after Trump, Part II: Searching for Truth in a Flood of Freedom

Life After Trump, Part III: The End of the Republican Alliance

Life After Trump, Part IV: Building a Better Democrat…Maybe

Life After Trump, Part V: The Opening Roster

Life After Trump, Part VI: The Crisis List—Russia

Life After Trump, Part VII: The Crisis List—The Middle East

Life After Trump, Part VIII: The Crisis List—China

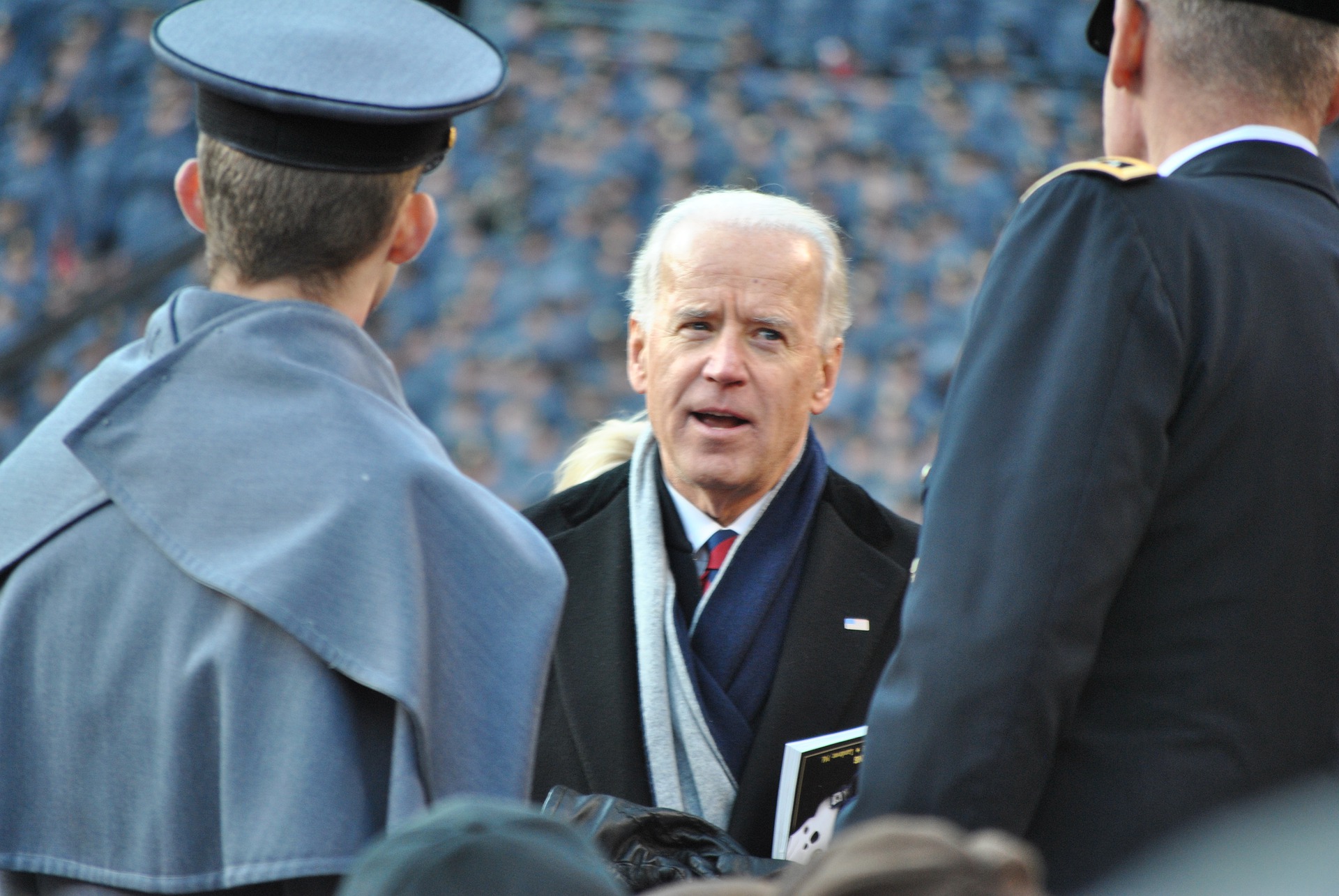

My original plan (such as it was) for this series was to use Part V to break down the foreign crises the Biden administration will face in his freshman year. We’ll still get to that (stay tuned for Part VI), but after going down Biden’s looooong list of political appointees I figured it’d be best to set the stage with the sorts of folks who will be laboring within the new administration.

I think the best way launch into my thoughts about the players is to echo a recent statement by Senator Marco Rubio (R, Fl) who blithely quipped they “will be polite & orderly caretakers of America’s decline.”

A bit rude? Sure. Pithy? Certainly. But that doesn’t make Rubio completely off base.

Biden’s picks are deliberately banal. I can see why. Biden is attempting to hold together the ungainly, dissatisfied coalition that brought him to power. Biden knows the only thing today’s Democrats agree on is that Trump is bad. As Biden saw up close during the Obama administration, if your entire raison-d’etre is merely to continue campaigning against your predecessor, you’ll never get much done. Biden needs his coalition to hold together if he is to take any action on domestic affairs, and that means he needs his foreign policy team to stay out of the spotlight. The best way to do that? Make sure they’re boring.

Even if Biden felt secure enough to spice things up, there’s little to draw upon. In recent decades the Democrats have experienced an utter collapse in foreign policy expertise. The Democrats were in opposition under W and Trump. Clinton was famously disinterested in the world, while Obama did nothing for eight years (going so far as to leave talented folks like John Kerry out to dry when they attempted to take strong stances). There is no one in the Democratic Party’s apparatus who has any meaningful experience doing anything outside of the United States.

Most of those who matter have only had professional lives of advising Biden either in the Senate or while he was VP. They’ve never advised someone who actually had decision-making capacity. So while they may know a lot and are generally sane and reasonable, they’ve never done very much.

There are exceptions of course. I’d like to call attention to the four who matter.

The first is the most straightforward: William Burns, a career diplomat with extensive bipartisan experience including lengthy and disturbing eventful stints in the Middle East and Russia. He’s a diplomats’ diplomat. Polite, yet firm, and known for speaking truth to power without being a jerk about it. He particularly excels at backchannel diplomacy with countries that loathe the United States. Considering the general mess of the world in the aftermath of Trump and Obama, America should count itself lucky that someone like Burns is even interested in government service.

I’m especially excited that Burns is not going to be part of the diplomatic core at the State Department, but instead will be leading the freakin’ Central Intelligence Agency. The CIA is responsible for the spooky stuff, and Russia is very active in the world of spookiness; I literally cannot think of an American alive who is more qualified to operate Club Cloak & Dagger at this moment in history.

Burns’s personal style also suggests he’ll be able to rebuild that most exotic and fretful of relationships: the one between the Agency and the White House. Clinton (in)famously sidelined the Agency (remember that idiot who tried to land a plane on the White House lawn? The Agency director at the time quipped it was just him trying to get a meeting with his boss). W Bush turned the Agency into a tactical support system for military operations in Iraq, gutting its ability to focus on the long game. Obama…well Obama just hermetically sealed himself in the West Wing and pretended the entire world outside of his personal ideology didn’t exist, government included. Trump screamed at any analyst who dared to refuse manufacturing evidence to support his latest tweet. After 28 years of strained Agency-presidential relations, someone with Burns’ record of bipartisanship, well of patience, topical depth, and easy-going approach is sorely needed.

There are only two things about the Burns appointment that bother me. First, Burns wasn’t Biden’s first choice, but instead his third, suggesting Biden’s talent-detector is in need of a tune-up. Second, Burns’ mustache is hideous and I’m hoping for a freak fireplace accident

Next we have Janet Yellen – former Federal Reserve Chairwoman and now Treasury Secretary.

Like Burns, Yellen may well be just what the doctor ordered. Let’s start by noting that as former Fed Chair she has loads of foreign policy experience. Yellen helped put the pieces of the world back together in the aftermath of the 2007-2009 financial crisis, and in doing so developed not only experience in diplomacy, but also considerable expertise in thinking outside of the box.

Many on the fiscal conservative side not-so-affectionately refer to Yellen in a variety of odious forms, thinking her to be no less than a demonic force seeking to end the modern financial system as we know it. In her term as Fed Chair she greatly expanded a process known as quantitative easing, which is the technical term for expanding the money supply (printing currency) and using that extra cash to buy up government and corporate debt to stabilize bond markets and keep borrowing costs as low as possible. The primary reason for fiscal conservatives’ vitriol is a concern for long-term economic damage, particularly in the form of inflation and warping of the rates of return within bond markets.

I don’t find such criticism entirely fair. For one, it wasn’t Yellen who initiated QE, but instead her predecessor; and it was her successor who massively expanded it. No one is calling them the Devil’s henchpersons.

For two, our collective understanding of economic norms is evolving. Shifts in global trade patterns, demographic collapses, and a mix of compounding technological improvements are challenging everything we think we know about economic theory. While we won’t know the full effects of QE for years to come, what we do know now is after a decade of ever-increasing volumes of monetization, inflation is lower than ever and America’s debt financing costs have gone down. Yellen was…right. For the moment at least.

So let me quote the lady herself: “With interest rates at historic lows, the smartest thing we can do is act big.” She’s probably right about that too. Biden’s out-of-the-gate economic plan is for a $1.9 trillion stimulus program. By far the biggest in US history. The fiscal conservative in me throws up in my mouth a little bit whenever I think about it, but fiscal conservative orthodoxy at the moment is clearly not what the doctor ordered. I’m glad a creative thinker who can still do math like Yellen is on the job.

The third appointee of note is to head the office of the U.S. Trade Representative, the bureau responsible for enforcing and negotiating all trade deals: Katherine Tai.

Tai is definitely not qualified to be a negotiator. Until mere days ago she was “just” a Congressional staffer. She’s certainly versed in all the relevant trade issues, but she’s never managed a big staff or participated in, much less led, a meaningful negotiation. Normally, I’d say that she – a politically-unwired technocrat – is a horrible choice.

You may have noticed, things aren’t normal these days.

One of the things Biden has made abundantly clear is he has no plans to even think about free trade negotiations until such time as the coronavirus crisis is firmly in the rear-view mirror. That won’t be until the fourth quarter of 2021.

Luckily for Tai, her predecessor – Robert Lighthizer (the same guy who renegotiated NAFTA) – has already done a lot of the heavy lifting for the singular negotiation Tai will be called upon to carry to the finish line: a trade deal with the United Kingdom. Considering the UK’s options for trade with anyone but the United States are so minimal as to be practically nonexistent, Tai shouldn’t face many problems. (Although she will undoubtedly be vilified in the British press for taking the British economy to the cleaners.)

But only having one trade deal on her plate does not mean Tai won’t be extremely busy. She might not have trade talks experience, but she is a trade lawyer. Biden picked her not because he wants a raft of new trade deals, but because he wants his USTR to sue the pants off of anyone who might not be adhering to the spirit and letter of US trade law. That’s pretty much everyone. Tai might be the wrong person for the title, but she is absolutely the right person for the job the new president wants tackled.

Finally, we come to the new National Security Advisor, Jake Sullivan.

Sullivan is a super-smart foreign policy generalist who understands the interlinkages of trade and populations and security that bind the world together and threaten to spin it apart. He has also apparently achieved the unthinkable: he is so painfully affable that everyone in DC likes him. He reminds me a lot of…me.

Which is why I’m pretty certain he will fail.

Somewhat contrary to the title, America’s National Security Advisor does a lot more than merely advise the president on foreign policy. He (or she) also has to ride herd on the government’s sprawling foreign policy apparatus. It is ultimately a bureaucratic job akin to riding an angry, rabid octopus.

The quintessential NSA in recent years was John Bolton. Bolton had decades of experience taking charge of this or that aspect of the foreign policy establishment and forcing them to do things his way to achieve his president’s goals. Most of Washington despised him, not because of a lack of competence, but instead because of his I-hate-everyone-because-everyone-is-a-moron personality. Bolton was (in)famous for intimidating and outmaneuvering his way through the entire bureaucracy. In contrast, Sullivan is a congenial brainiac. The very knowledge base that leads Biden to rely upon Sullivan’s thinking is guaranteed to piss off career civil servants convinced that they know more about topics x, y or z. Bottom line? People like Sullivan (and myself) – deep-thinking, purposefully-rounded generalists – tend to do very badly in government.

And even if Sullivan proves me wrong and is indeed the right person for the job, his first task has an Augean Stables stench about it. He’ll need to re-create America’s foreign policy establishment.

Under W, Obama, and Trump the foreign policy apparatus has been badly mismanaged, irresponsibly re-tasked, malignly ignored, intentionally belittled and intellectually castrated. The past 20 years have convinced smart, ambitious, principled people that government work isn’t for them. Sullivan doesn’t have much to draw upon except the clock-punching hangers-on who are holding out for a pension. He’ll need to rebuild many bureaus from scratch and it isn’t clear he has the expertise, mindset or rolodex to even begin. The State Department in particular needs a demo crew more than a superwonk. Sullivan is going to engage in such holistic institutional reconstruction while serving as America’s foreign policy guru? I think not.

I’d be thrilled if Sullivan proves me wrong and instead shines. I’d be thrilled if people like myself could actually be part of the solution. But I’d also be shocked.

Now let’s set the stage for the Biden administration’s opening environment at home.

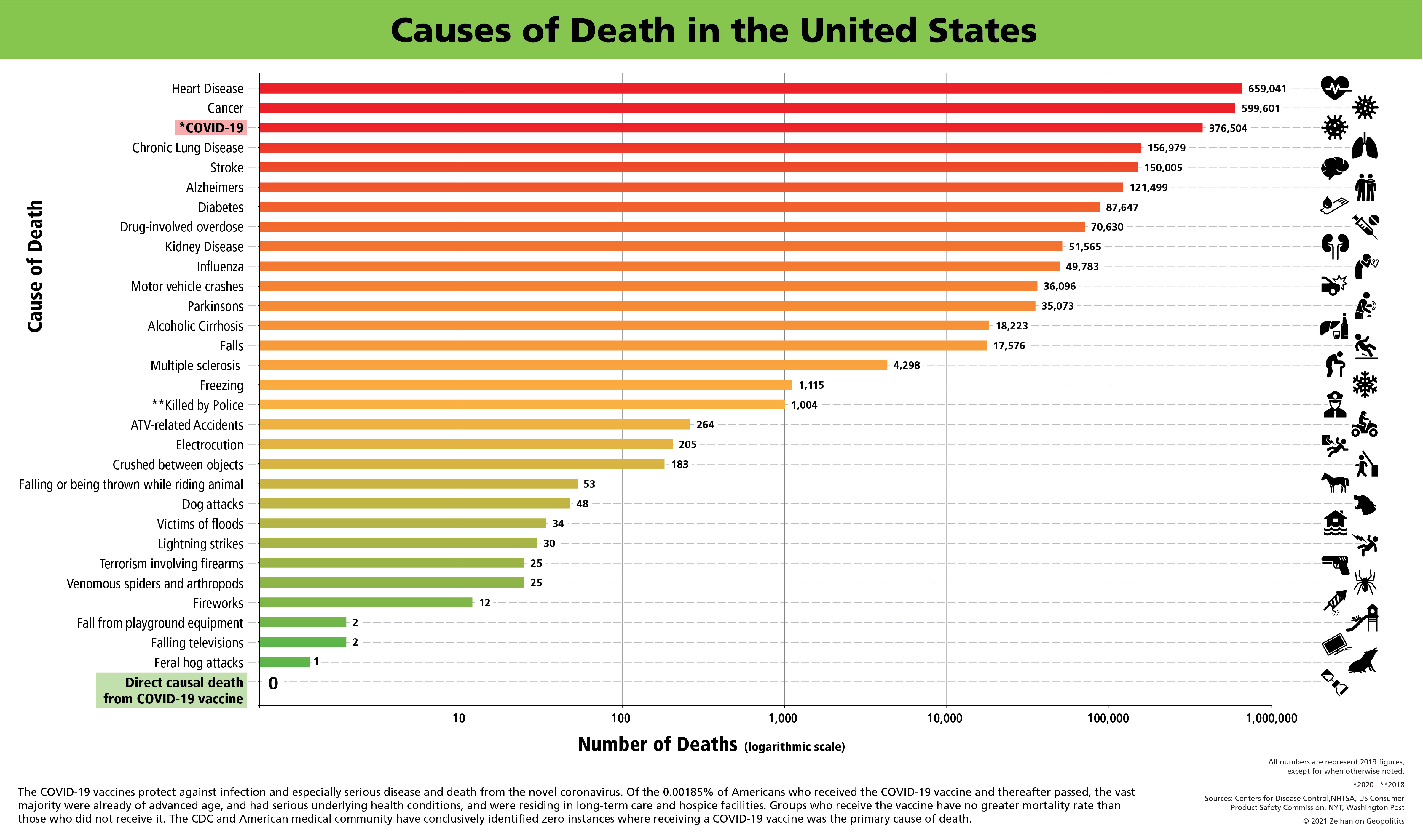

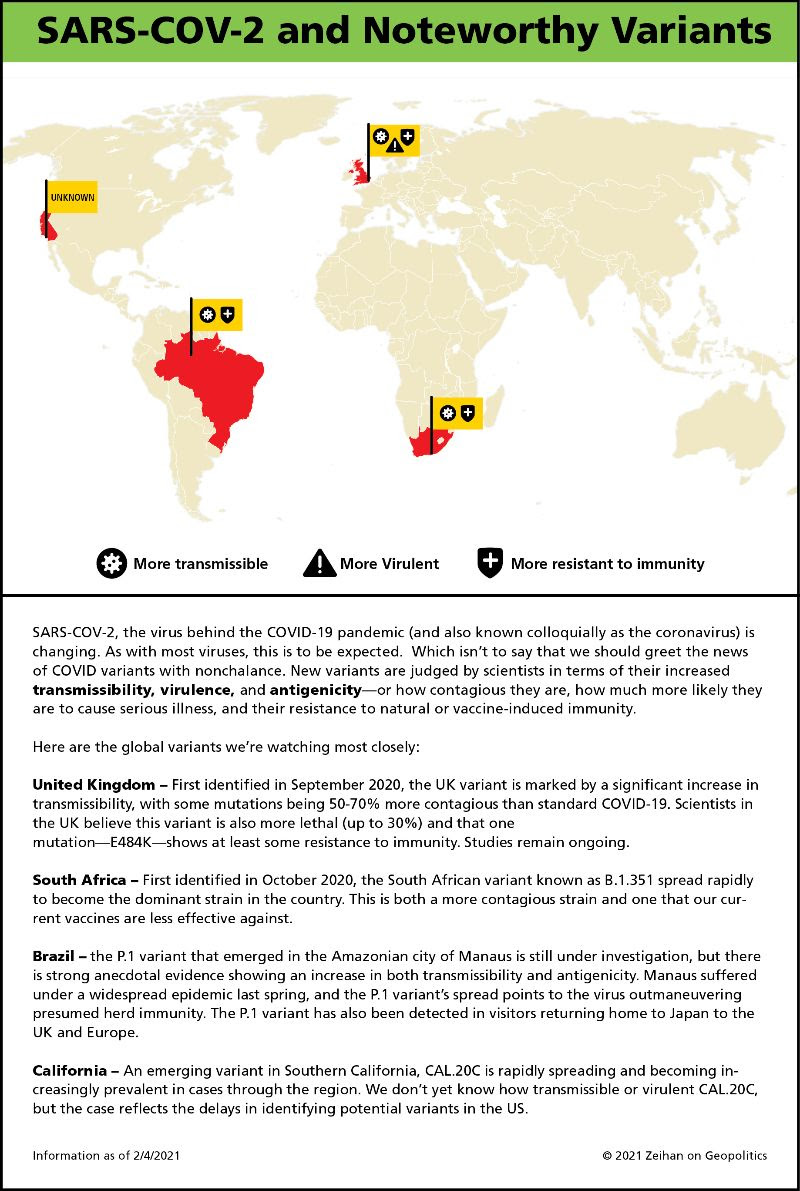

The coronavirus crisis is epically raging. Daily deaths have exceeded the number of Americans’ killed on September 11, 2001 for a few weeks straight. Total deaths have now exceeded total American deaths in the four years of America’s most deadly war, World War II.

But the numbers are turning. The post-Christmas surge has peaked and new hospitalizations are ebbing. Add in some Biden-related actions such as mask mandates on federal properties, and we should see a very rapid drop off in infections in the month to come. The US already has two vaccines on the market, with another two likely to join them around mid-February, one of which – the Johnson & Johnson formula – can be stored in a normal refrigerator and only requires a single shot. Even better, J&J expects to have 100 million doses distributed by April 1.

Epidemiologically speaking, that puts us in a race between people relaxing their guard as the post-Christmas surge fades, and vaccines getting into arms. If the vaccines win the race, roughly 100,000 fewer people will die and it will appear to the general public that all defeating the vaccine required was Biden in the White House. Before you root for that not to happen, keep in mind the alternate interpretation of Biden failure requires at least another 100,000 deaths.

My point here is not simply that Biden enjoys fortuitous timing, but that coronavirus in general has presented the new president with a very favorable starting conditions. While everyone has different opinions on the specifics, everyone knows we need a new stimulus package to battle the virus and its economic effects. Biden’s singular known skill is that he’s a Senate negotiator. This battle plays directly to his strengths, and he’ll reap the political gains for getting it done.

Between the vaccine rollout, the COVID mitigation package, and some very basic anti-virus measures (that honestly Trump should have done last March), Biden has the opportunity to shine. He has the opportunity to build domestic unity. He has the opportunity to look competent. He has the opportunity to look powerful. And he has the opportunity to look gracious.

These are all very easy carries that will reap mounds of political capital he can use on other projects. But if Biden cannot manage this we will know that he really is incapable, and that the next four years will be just as disconnected as the previous four.

Best of luck to him, because there are already some hefty issues clamoring for presidential attention.

Coming soon:

Life After Trump, Part VI: The Crisis List

If you enjoy our free newsletters, the team at Zeihan on Geopolitics asks you to consider donating to Feeding America.

The economic lockdowns in the wake of COVID-19 left many without jobs and additional tens of millions of people, including children, without reliable food. Feeding America works with food manufacturers and suppliers to provide meals for those in need and provides direct support to America’s food banks.

Food pantries are facing declining donations from grocery stores with stretched supply chains. At the same time, they are doing what they can to quickly scale their operations to meet demand. But they need donations – they need cash – to do so now.

Feeding America is a great way to help in difficult times.

The team at Zeihan on Geopolitics thanks you and hopes you continue to enjoy our work.

DONATE TO FEEDING AMERICA