Americans are currently struggling with inflation and certain categories, like fuel prices, get an outsized amount of attention. It makes sense. There are few products people buy as frequently that have as volatile a pricing scheme. It’s also universal. In a car-driven society, the pain at the pump is a metric most people are aware of.

But inflation certainly doesn’t stop there. Everything gets more expensive. But for many items, like cars and kitchen cabinets, purchases are typically few and far between. In terms of social and political stability globally, food prices are something that I find much more concerning.

The United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization does amazing work tracking global food prices and agricultural trends. They do work on par with the USDA, and I consider both to be preeminent sources of information in their field on the topic of American/global agriculture. And they publish their information for free.

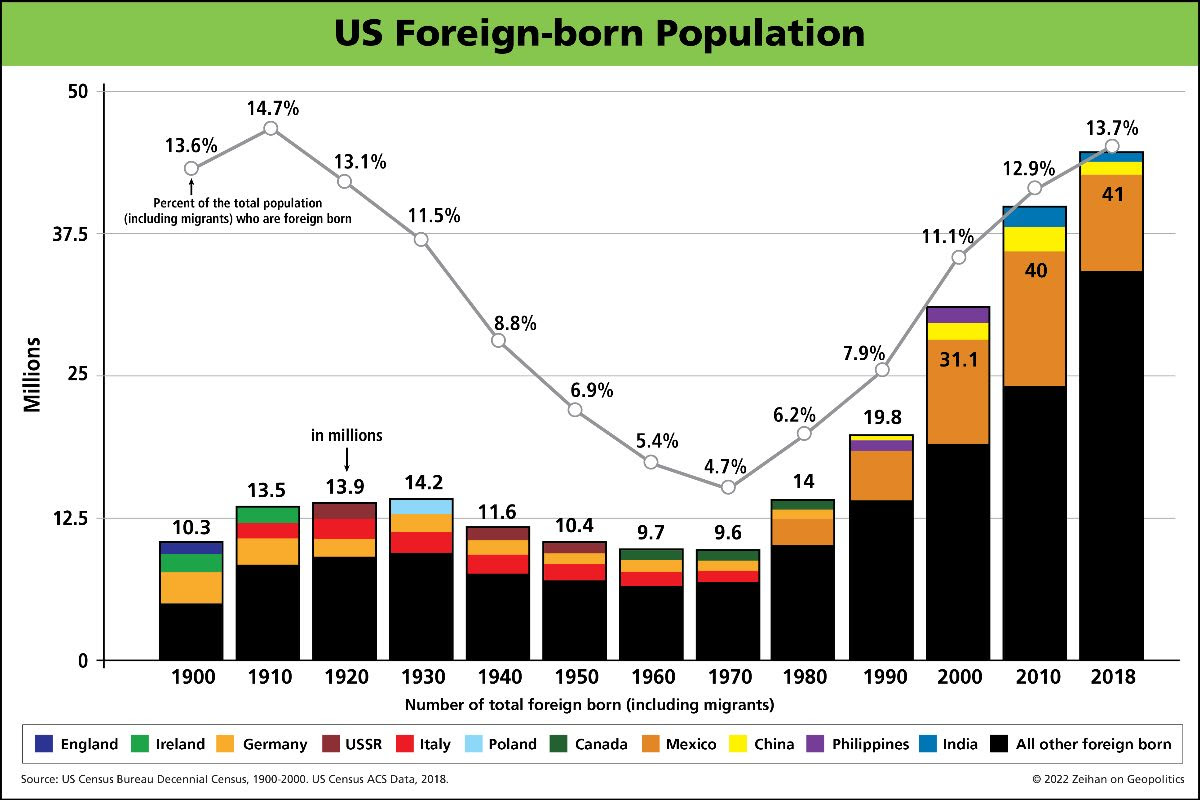

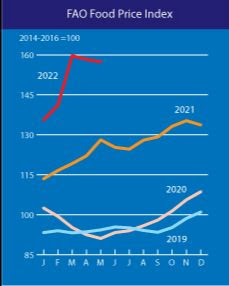

The FAO publishes monthly updates to global food prices. The picture is…not good. We’ve seen global food inflation drop a couple ticks in April and May of 2022 due to some softening in global oilseed markets (Indonesia has relaxed their palm oil export ban a bit, and we’ve seen some declining demand for oil seeds due to price) but the overall picture is still one of a stark increase in food costs. It’s a product of both an overall global inflationary environment, and a series of shortages due to conflict and poor weather (like the challenges facing Ukraine’s grain exports).

Let’s look at a couple of charts pulled from the latest FAO report (seen here):

2021, shown as the orange line, saw a pretty steady and straightforward increase in food prices between January and December, well over 2020 (in pink). 2022 is the aggressive, near-vertical line in red. The flattening out we see is again in large part due to some relaxation in food oil prices, but the news is certainly not good for global consumers. (And all of us in that bucket!)

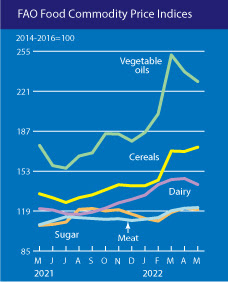

If you want to break costs down into primary commodity groups, the FAO has you covered there as well. Peek at the second chart. Vegetable oils, the top line in green, is showing the greatest year-on-year increase. But prices have risen steadily across all globally traded commodity groups like cereals (including wheat) and dairy. We’ll have to see how the sugar harvest plays out in Brazil this year, but meat prices are also slowly but steadily inching upwards–as much a product of rising feed import costs as it is growing demand for poultry and fears over a widening avian flu epidemic.

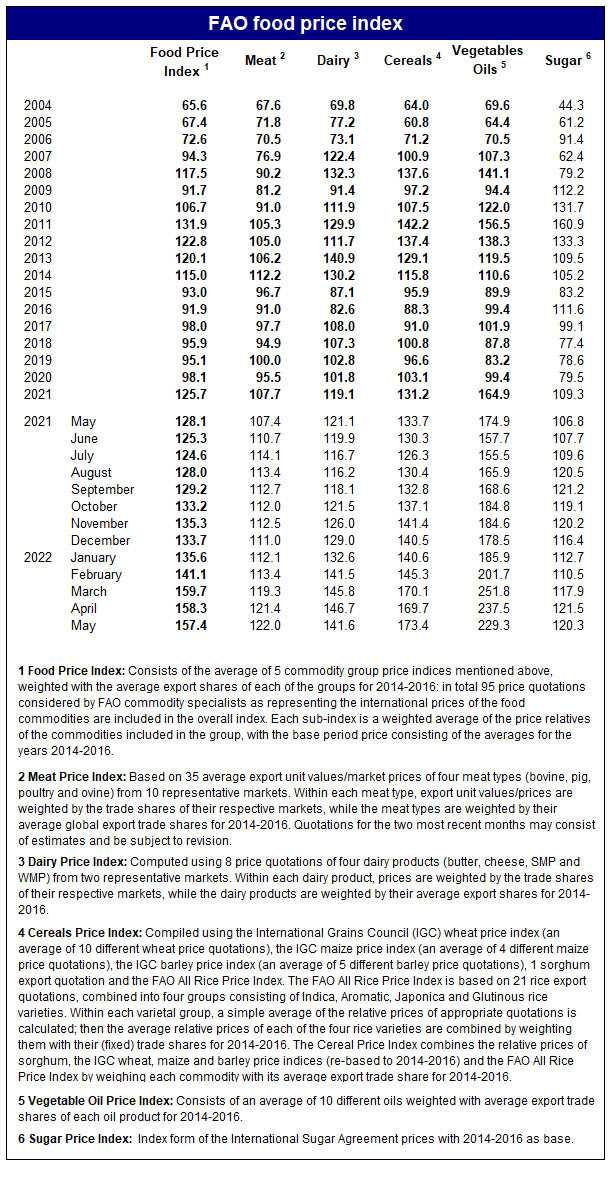

If you prefer numbers, we can see that we’re already at or near historic high prices for almost all major commodity groups going back close to 20 years:

All of which represent a more expensive global food price environment. Large importers of food like Egypt are already scrambling and, according to some, purchasing Russian cargoes of stolen Ukrainian wheat. This is an issue that the US is starting to take seriously. And for countries dependent on food aid, like Syria and Yemen? Challenges abound, to say the least. While this is only one part of the global inflation story, it is one that most people globally will feel most acutely.

We invite those of you who are interested to join us today, June 8th, for our webinar, Inflation: Navigating the New Normal. More information at the sign up link below. Unable to attend the webinar live? No problem. All paid registrants and attendees will be able to access a recording of the presentation as well as a PDF of presentation materials.

Can’t register for the live event? Not to worry. We’ll be sharing how you can still buy access to the recording and presentation materials in the future.

Here at Zeihan On Geopolitics we select a single charity to sponsor. We have two criteria:

First, we look across the world and use our skill sets to identify where the needs are most acute. Second, we look for an institution with preexisting networks for both materials gathering and aid distribution. That way we know every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence. Then we give what we can.

Today, our chosen charity is a group called Medshare, which provides emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it. Until future notice, every cent we earn from every book we sell in every format through every retailer is going to Medshare’s Ukraine fund.

And then there’s you.

Our newsletters and videologues are not only free, they will always be free. We also will never share your contact information with anyone. All we ask is that if you find one of our releases in any way useful, that you make a donation to Medshare. Over one third of Ukraine’s pre-war population has either been forced from their homes, kidnapped and shipped to Russia, or is trying to survive in occupied lands. This is our way to help who we can. Please, join us.

CLICK HERE TO SUPPORT MEDSHARE’S UKRAINE FUND

CLICK HERE TO SUPPORT MEDSHARE’S EFFORTS GLOBALLY