Our next Live Q&A on Patreon is here! On April 9, Peter will join the Analyst members on Patreon for question time! In order to get in on the fun, join the ‘Analyst tier’ on Patreon before April 9.

You can join the Patreon page by clicking here

As the Trump administration shifts US foreign policy, several countries are taking notice of the rising global instability. It looks like the nuclear question is getting thrown around by quite a few of those countries.

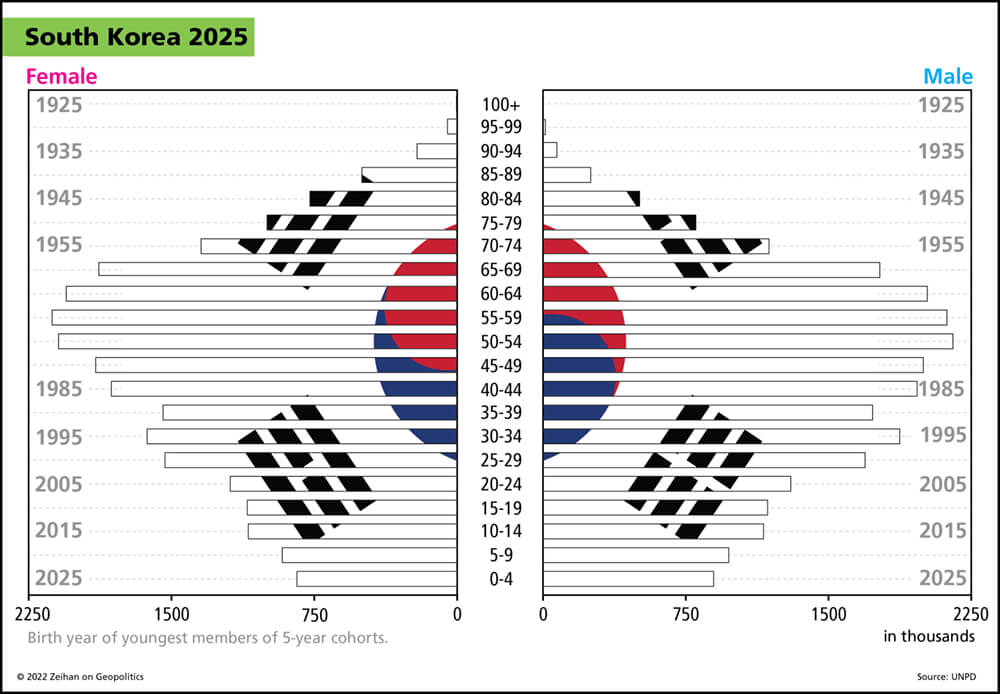

The US cancelled defense talks with South Korea following the (Korean) president’s impeachment. As a result, the South Koreans are now revisiting policies that would allow them to develop nuclear weapons, quickly. However, Seoul isn’t the only place these discussions are happening.

Feeling the US can no longer be relied upon for protection, places like Ukraine, Poland, Germany, Sweden, Finland, Romania, Japan, and Taiwan are all considering nuclear armament in varying degrees. This strays from the long-standing policy where the US would provide security in exchange for control over global defense policies.

With large scale nuclear proliferation now on the table, the risk of conflict (and use of these weapons) will grow. And more shiny, red buttons isn’t quite what the world needs right now.

Here at Zeihan on Geopolitics, our chosen charity partner is MedShare. They provide emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it, so we can be sure that every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence.

For those who would like to donate directly to MedShare or to learn more about their efforts, you can click this link.

Transcript

Hey everybody. Peter Zeihan here coming to you from the Home Office. Apologize for being inside, but there’s 70 mile an hour winds outside, and recording is just not possible. Today is the 17th of March, and the news is that American Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth just canceled defense talks with the South Koreans. He had a really good reason for doing it.

The South Koreans functionally don’t have a government right now. The former president was impeached, currently out on bail, which just feels weird linking those words together. And they haven’t had new elections yet, so there really is no one of authority to speak to about really deep strategic issues. And there is a very deep strategic issue that needs to be discussed.

The South Koreans have been looking at what the Trump administration has been doing with Ukraine and the European allies and even badmouthing, the Japanese of late. And they are coming to the unfortunate conclusion that they are going to have to go it alone on their defense policy. Now, South Korean military forces have basically been under this American umbrella, not just in terms of actual security protection, but actually leadership since the Cold War.

If a War were to break out, and the North Koreans were to invade South Korea, technically the entire South Korean military is under American command, even though there’s only about 30, 35,000 American troops on the peninsula, compared to, you know, ten times that for South Koreans. In addition, the South Koreans are one of the few countries that by Donald Trump standards have actually met their defense procurement goals over the course of this last several decades, typically spending more than 3 to 3.5% on defense the entire time, which is kind of the range that Donald Trump until recently said we were supposed to be in.

And at the moment, the Trump administration hasn’t really bad mouth the South Koreans in any way, like they have the Germans or the Italians or the Brits or the French or the Ukrainians or the, you know, it’s a long list give you the point. Anyway, the South Koreans see the reading, writing on the wall because they realize they are not what you would call a major ally.

The South Koreans are not capable of deploying forces really outside of their theater. And so they are definitely in the category of defense consumer. Regardless of how much of the week they try to shoulder themselves. And their concern is if the Trump administration just turns his eyes to them. But it’s just a matter of time before the United States moves on.

And so they are dusting off the policies from the 60s, 70s and 80s that would allow them to do a sprint to a nuclear weapon. In a matter of weeks, if not decades. And this has earned them the labor by the United States of sensitive energy country, meaning that they are no longer a complete non concern when it comes to nuclear proliferation.

But now something where it’s on the radar and that’s exactly where they should be, and having a discussion at the very top level between the Americans and the South Koreans on what can and would and should happen under all these scenarios is exactly what needs to happen.

But there’s no one to have that conversation takes up at the moment. So delay, South Korea is hardly the only country that is going to be in this bucket. We have a number of other countries who are concerned about what the United States is doing, and realize that they need to, or coming to the conclusion that they need to come up with their own defense plans.

And one of the things you have to consider if you haven’t had a sufficiently strong conventional force for a while, you know, like South Korea has, building up this conventional forces takes years, if not decades. So can they be American general staff situation is 50 years in the making. Aircraft carriers, from the point that you decide that you want to do it, you go through the design, you go to the current, you go through manufacturing, and then finally field testing.

You know, you have the 20 to 25 year process. Considering the speed at which things are unraveling in Europe, most countries just don’t have that sort of time. And so countries who want to actually look out for themselves, they can’t really rely on conventional forces in the short or medium term, which raises the question of nuclear weapons. The country that is, of course, under the greatest pressure is Ukraine.

And we’re supposed to have a conversation very soon between Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin of Russia, which will give some indication just how much Ukrainian territory, the Americans are willing to sacrifice in order to achieve a peace deal. But keep in mind that there are multiple nuclear power reactors in Ukraine. And Ukraine used to be where all the brains of the Soviet military industrial complex used to be on nuke issues, on aircraft issues, and on missile issues.

So the idea that the Ukrainians, when under pressure can’t go nuclear is silly. Next slide of countries in that are already publicly discussing who, where and how to get the nukes. Poland’s at the top of that list. They’ve actively asked the United States to deploy nuclear weapons to their soil, and that has gotten broadly rebuffed. And so now they’re discussing what they need to do to get their own, the road for Poland will be a little bit longer.

They don’t have a native nuclear industry, but their manufacturing capacity is robust. All they have to do is get the nuclear material and they’d be off to the races. It would probably take them 3 to 9 months in order to get a functional weapon, not an explosive device. They could probably do that in the weeks, but the actual deliverable weapon, probably within 3 to 9 months, the next country up is the one that I am, of course, most worried about.

That’s Germany. They’re having the discussion. Not should we get nukes? But how should we get nukes? Option one is to partner up with the French and pay money to the French, so that the French nuclear deterrent, which has existed since the 50s, also covers Germany. But at the end of the day, the French are the ones who would control that arsenal and whether or not it should be used or not.

And so the other option is for the Germans to get as close to the threshold as they possibly can get experience in doing the milling in order to make the warheads enriching uranium with the plutonium. And again, they have a nuclear industry so they can do this themselves, and the idea that the Germans could not put into the device into a deliverable weapon system.

The Germans have been arms manufacturers for a very long time. That would not be a challenge. In between, look to Sweden and Finland. Here are two countries that, like Ukraine, already have an indigenous nuclear civilian fleet. And the Swedes, like the Germans, already have an indigenous, robust military system, for contracting and manufacture. Both of them are openly discussing these options.

And if they do decide to pull the trigger, both of them would have a deliverable weapon in under a month. Rounding out the list in Europe, look to Romania. Like the Ukrainians, they have a nuclear industry. However, the weapon systems are subpar and pretty much all important. So they could get a device, use it as a failsafe.

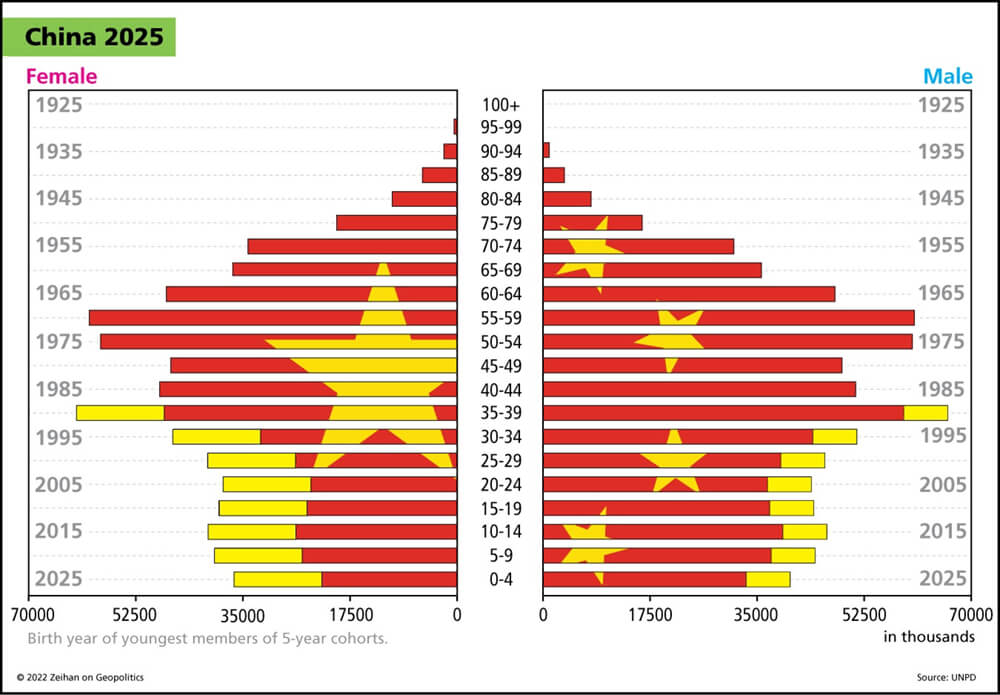

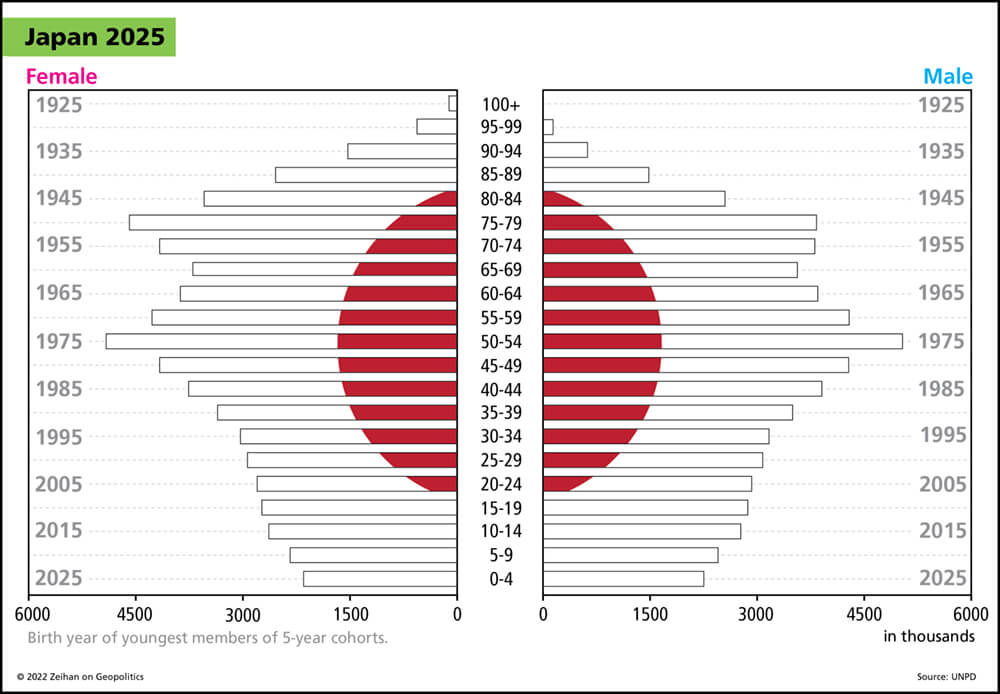

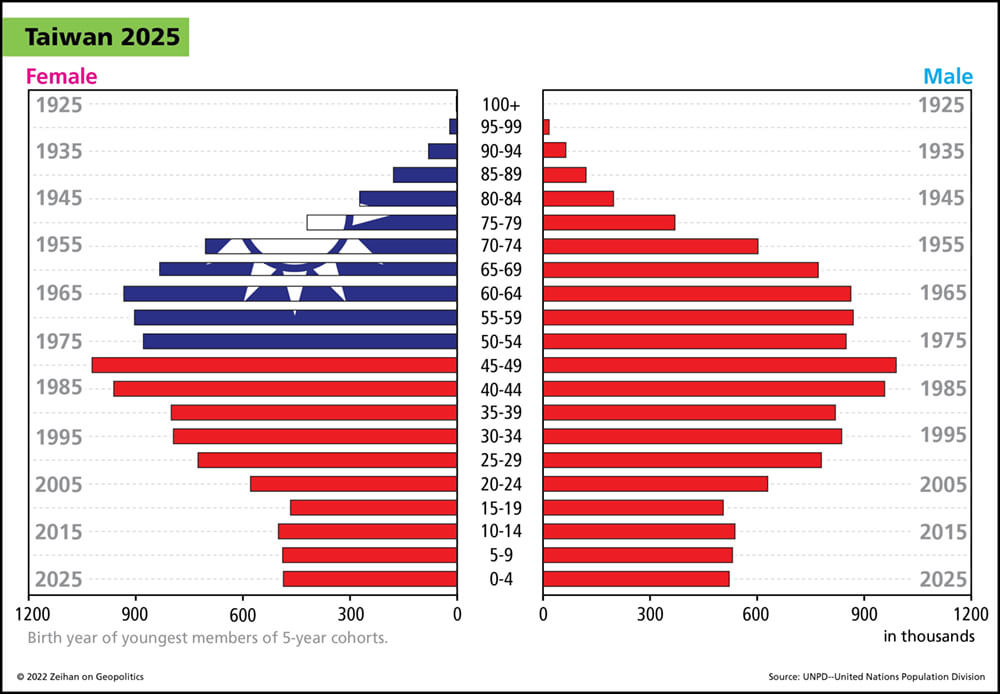

But getting the deliverable system would be, probably a bridge too far. And anything less than a 12 month timeframe. But it’s a lot faster than doubling the size of your army. Over in East Asia, in addition to the Koreans, the two countries to watch, obviously, are Japan and Taiwan. Both have a arms industry. Both have the materials.

Both have plenty of scientists and engineers who have experience with both. You just have to marry the two together. It’s just a question of how many funds they decide to put behind it. And in the case of Taiwan, if they really did feel that the Americans were leaving, well, they really don’t have any option but to get nukes.

And while the Japanese Navy may be much more powerful in terms of reach in the Chinese Navy, the home islands are within range of a lot of Chinese weapons systems. And so if there was a war, I don’t doubt who would win in the end because the Japanese could choke off the Chinese mainland. But the damage could be extreme.

About the only way to mitigate the risk there is deterrence. And that means nukes. So they’re we’re talking about eight countries that are likely to pick up nukes in the not too distant future, based on how American policy unfolds in the next several weeks to months. Something the Trump administration is learning is something that every administration before it has learned it, including the first Trump administration, is that if you want to write everyone’s security policies, you have to give them something.

And during the Cold War, and until very recently, it was a guns for butter trade, the US would protect global sea lanes so that anyone could trade with anyone at any time. And in exchange, the allies allowed Washington to write their security policies. What the Trump administration is doing is not just breaking that deal, but saying that we’re not going to protect your trade.

You are on your own, but you’re also on your own for defense. And that forces all of these countries to take matters into their own hands. And if they do that, the United States loses the ability to say what can and cannot happen with weapons systems. And that leads to a world with a lot more nukes. And it a much, much, much higher likelihood of actually having a weapons exchange.