The past few weeks have been…eventful. I make my living anticipating and explaining and projecting change, with an unfortunate emphasis on destabilizing and disintegrative change. Pre-coronavirus the world was already hurtling through its most rapid breakdown in living memory; Coronavirus has accelerated…everything.

Times of extreme change are often painful, but for many they provide opportunity. Leaders often shine during times of extreme change. History tends to remember people who help their people and institutions navigate periods of disruption. Reagan’s speech at the Berlin Wall ended the Cold War. Yeltsin standing on a tank, defying the military put a bullet in the Soviet brain. Meir launching a worldwide assassination program made tiny Israel a global power. Churchill pledging to never surrender set the stage for the Nazi defeat. Ataturk defying Europe’s post-WWI carve-up plans ensured that, eventually, the Turks would return as a major power. In moments like these, a few countries pull away from the pack and reinvent themselves.

I haven’t seen any of that so far in the coronavirus crisis. Anywhere. Honestly, it is a little disappointing that no world leaders are rising to the challenge. While some leaders have dealt with the crisis competently, I haven’t seen any effort by any leader to harness the crisis to put their country on a more solid footing or to prepare for the post-COVID future. The lack of global leadership effort is simply mindboggling.

Let’s run through the list:

Emmanuel Macron has hitched his star to the idea that EU countries with solid budgets (that is, the countries less spendthrift than France) should shell out more money to help the poorer countries (that is, countries like France) get by. That certainly generates him some gravitas in Rome and Lisbon, but personifying the concept of asking for a hand-out isn’t what leadership looks like.

Germany’s Angela Merkel was supposed to be retired by now. Her chosen successor stepped back in early February, just before we all became obsessed with coronavirus. With her retirement plan in tatters, the Indispensable European is now once more unto the breach, dealing with intractable issues in her quiet, competent way. Unfortunately, she is constrained by her country’s savings-obsessed culture. No one in Germany wants to bail out Europe’s weaker members, particularly since Germany’s forward-looking, keep-your-powder-dry medical and financial approach has (so far) proven successful while Southern Europe’s spend-it-even-if-you-haven’t-got-it mindset has not. Honestly, Merkel looks like she’s just tired of it all. I feel exhausted just reading about her. (And frankly, she should be tired. She’s been shoveling Europe’s shit for over a decade.)

Even if everyone loved Brexit and how Prime Minister Boris Johnson has handled it, Johnson just now emerged from some quality time in a freaking COVID ward (just in time to bring his new baby home). The UK in general – and Johnson in particular – is in no shape to lead much of anything.

The orders to tamp down any discussion of coronavirus in Japan in order to maximize the chance of the 2020 Summer Olympics being derailed undoubtedly came from the top, making Prime Minister Shinzo Abe directly culpable in a spreading epidemic in the world’s oldest national demographic. Needless to say, few are looking to Tokyo for a how-to guide.

Canada’s Justin Trudeau has the look of a man who has been completely overtaken by events…because he has been. That’s less a judgment of his leadership or his team’s management skills, and more the crystallizing realization in Canada that there is no future for Canada unless it does everything of substance hand-in-glove with the United States. That includes trade policy and energy policy and China policy and…anti-COVID efforts. Trudeau has been (repeatedly) blindsided by whatever fresh spasms of oddity have erupted from the White House, and he simply has no option but to make the best of it. Pragmatic? Yes. Necessary? Certainly. But the liberal flame has most certainly gutted out.

Russia’s Vladimir Putin proudly proclaimed Russia had COVID “under control” just ten days before the Moscow mayor launched a lock down. There’s been broad spectrum public criticism by health care workers of the Russian government’s (mis)management of the epidemic, that has progressed to several doctors committing suicide by jumping out of buildings (a favorite technique of the Russian security services for disposing of troublesome personalities). This would be bad enough at any time, but Russia’s educational system collapse in the 1990s means Russia doesn’t have a particularly deep bench of health care staffers. COVID combined with the government’s response to the bad PR coming out of the health care sector is gutting what’s left of an already woefully inadequate health care infrastructure. Needless to say, while many countries want to manage the message, no one else is liquidating their precious health care workers to do so. (And incidentally, the Russian bot farms are hard at work spreading bat-shit crazy COVID-related conspiracy theories so please quit getting your COVID news from Facebook.)

Not to be left out, most of the world’s secondary powers have slightly wacky nationalist leaders who are proving…wackier with every passing day.

India’s Modi is working diligently to disenfranchise a large portion of his own population, and seems genuinely surprised when there is (violent) push back.

Turkey’s Erdogan is gayly skipping his way down a neofascist path, setting the stage for (another) harsh, ethnic-based, wipe-out of a conflict with the Arabs to the south, the Europeans to the northwest, and the Russians to the northeast.

Brazil’s Bolsonaro seems committed to ensuring the epidemic hits his country as hard as possible, in part by personally leading press-the-flesh rallies against COVID-containment and mitigation efforts.

Mexico’s Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador is nearly as obtuse on the topic of the virus as Bolsonaro. Moreover, he has decided against providing much of any support to Mexican firms during the crisis, ensuring that Mexico’s recession will be longer and more difficult than it needed to be.

The number of leaders who have risen to the occasion is vanishingly small. Korea’s Moon Jae-in and Taiwan’s Tsai Ing-wen have done a phenomenal job of managing the COVID epidemic, but much of the credit must go to those countries’ intelligence and diplomatic corps who are arguably the most attuned to regional disruptions. After all, for them threat detection/assessment is a matter of day-to-day survival, and their hawklike watching of China is what provided their countries’ health services with the advance warning the situation necessitated.

Honestly, the only leader who has truly outperformed is Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern of New Zealand. But while Ms Ardern continues to impress, her country’s geographic isolation grants the Kiwis virus containment/limitation options denied the rest of humanity. There are a few lessons there for others, but only a few. Yet even with these three bright spots, no one outside of their respective countries is looking to Moon or Tsai or Ardern for leadership.

That holds true pretty much everywhere. With the possible exception of Angela Merkel, not many people have looked to any of these leaders to be authorities on regional issues, much less global ones…ever. Part and parcel of true global leadership is that there can really only be one. Since the Americans for the past 70 years have provided the security architecture and economic capacity for a global system to exist, it has fallen to the man in the White House to design the response, set the course, provide the resources and, to be blunt, lead. That’s triply true in the case of the meaningful international institutions which provide the sinew of global cooperation.

Those days are over.

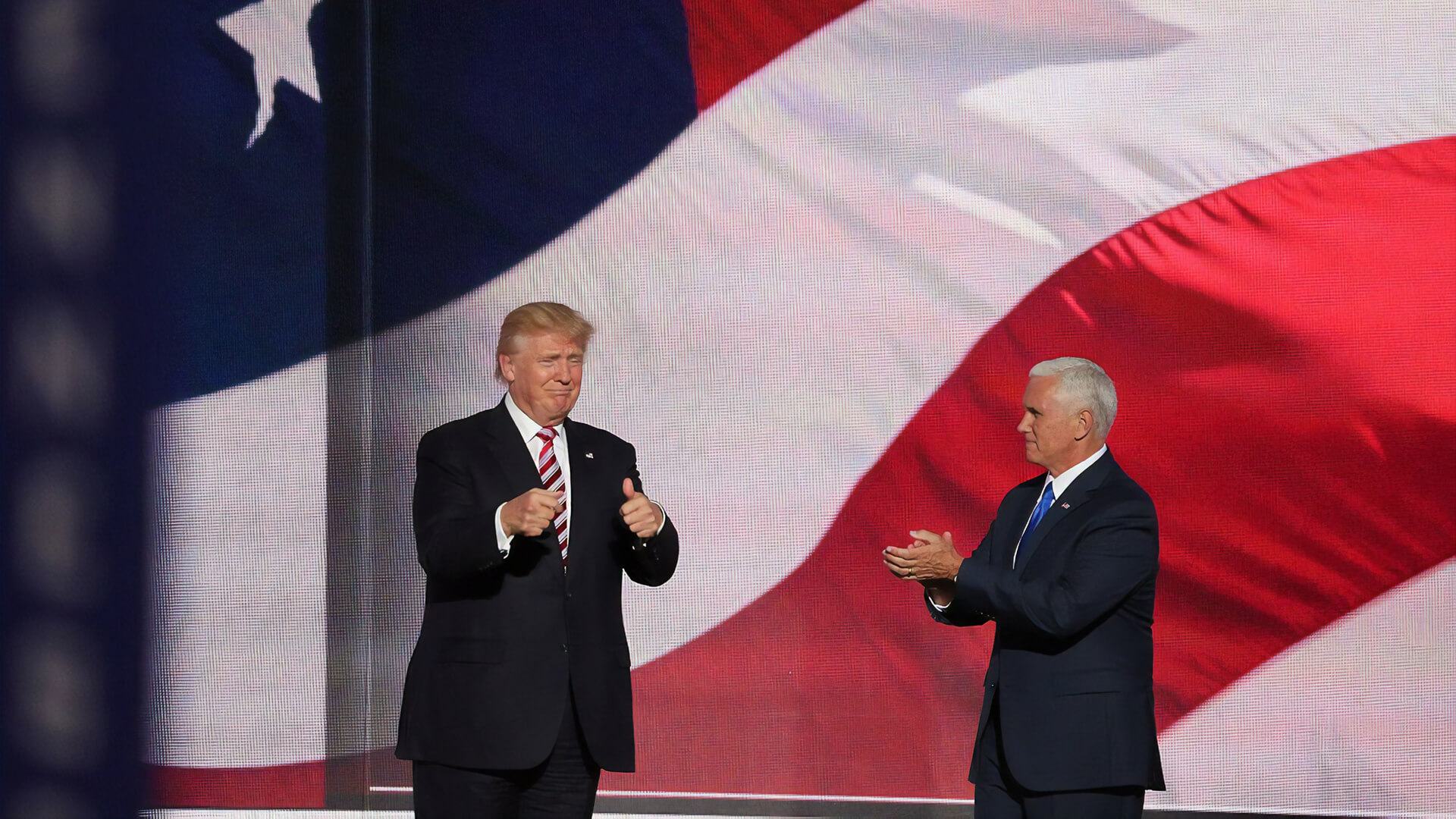

Since his election, Donald Trump has functionally ended NATO, eliminating the single greatest security alliance in human history. Last year the Trump administration functionally destroyed the World Trade Organization, the only institution capable of empowering the multilateral trading system. Last month the Trump administration ended American funding for the World Health Organization. A flawed institution? Sure. But to abandon it during a pandemic was, in a word, questionable. The American alliance with South Korea – long one of America’s three most loyal allies – is likely to end this year at Trump’s behest. TeamTrump is even drawing up plans to pull intelligence assets out of the United Kingdom, America’s oldest, closest, and most capable ally, in protest over the Kingdom’s Huawei-linked telecoms policy.

It doesn’t really matter whether you think Trump’s actions are warranted or otherwise. The point is that the United States de facto controlled these institutions and alliances. By leaving or killing them while simultaneously failing to establish domestically-run alternatives, Trump has vastly reduced the ability of the United States to manipulate the world. That isn’t leadership. That is abdication.

Nor is it purely an international question. Domestically, Trump is a standout in that the longer he is in the White House, the less competent he appears to be at using the tools of domestic power.

I’m not talking here about Trump’s politics, policies, or even personality, but about his gob-smacking lack of managerial skills. Nearly three and a half years into his term, there are still hundreds of positions throughout the federal bureaucracy which remain unfilled, a disturbing number of which deal with issues of health. Headless bureaucracies are broadly useless except to carry out the last orders that they were given. It is with more than a touch of irony that I must note that despite all sound and fury to the contrary, Trump’s pathological unwillingness to engage with the federal bureaucracies has actually entrenched Obama’s regulatory disfunction rather than excised it.

Nor has much of what Trump has done trimmed those bureaucracies down to size. After all, reducing staff and mandates and budgetary outlays takes active leadership, and Trump is one singularly disinterested and disengaged leader. Since Trump hasn’t disbanded the agencies or programs, America has been landed with all the expenses of a sprawling bureaucracy, but few of the benefits.

Add in daily COVID briefings in which Trump seems pathologically committed to showcasing his furiously deliberate lack of knowledge, and Trump’s levels of respect at home and abroad are at the lowest of his presidency – and trending very firmly down. Imagine how weak he will look in a few months (weeks?) when the United States experiences its second coronavirus wave.

Absent from this list of not-necessarily-failed-but-certainly-not-successful leaders is, of course, China’s Chairman Xi Jinping. Understanding just how disastrously Xi has mismanaged the coronavirus crisis and just how much permanent, irrevocable damage his “leadership” is causing China requires an entirely independent newsletter.

Stay tuned for Part II…

With the world under COVID-related lockdowns, I’m pretty much as home-bound as everyone else. That’s nudged me to launch video conferences for interested parties on topics ranging from food safety to energy markets to the nature of the epidemic in the developing world. While most of these events are for a set fee, my next video conference will be free of charge. Space, however, will be limited.

Join me May 19 for a once around the world of where we stand in the current crisis. Which countries are suffering most critically? Which are pulling ahead? What the shape of the pandemic will be in the weeks and months to come? What will the world look like once coronavirus is in our collective rear-view mirror? As with all the video conferences, attendees will have the opportunity to submit questions during the event.

Newsletters from Zeihan on Geopolitics have always been and always will be free of charge. However, if you enjoy them or find them useful, please consider showing your appreciation via a donation to Feeding America. One of the biggest problems the United States faces at present is food dislocation: pre-COVID, nearly 40% of all foods were not consumed at home. Instead they were destined for places like restaurants and college dorms. Shifting the supply chain to grocery stores takes time and money, but people need food now. Some 23 million students used to be on school lunches, for example. That servicing has evaporated. Feeding America helps bridge the gap between America’s food supply (which remains robust) and its demand (which coronavirus has shifted faster than the supply chains can keep up).

A little goes a very long way. For a single dollar, FA can feed one person for three days.