The Boomers are the largest generation the world has ever seen. And they’re getting ready to enter retirement en masse. This is going to have incredible impacts on global labor, capital and development. If you enjoy this video, I cover the topic of demographics and the future of, well, everything in depth in my new book The End of the World is Just the Beginning, available everywhere–including your local bookstore.

First things first: labor. As the largest–and longest lasting–component of the American and global labor force in history, the Boomers have had an outsized impact on everything. On wages. On hiring. On how subsequent generations–Gen X and the Millennials–fit into the labor market. Or don’t.

And now they’re retiring. While this leaves members of Gen X as the most skilled labor cadre in the United States, our numbers can’t replace the Boomers. And the Millennials lack the decades of skill to replace Boomer workers.

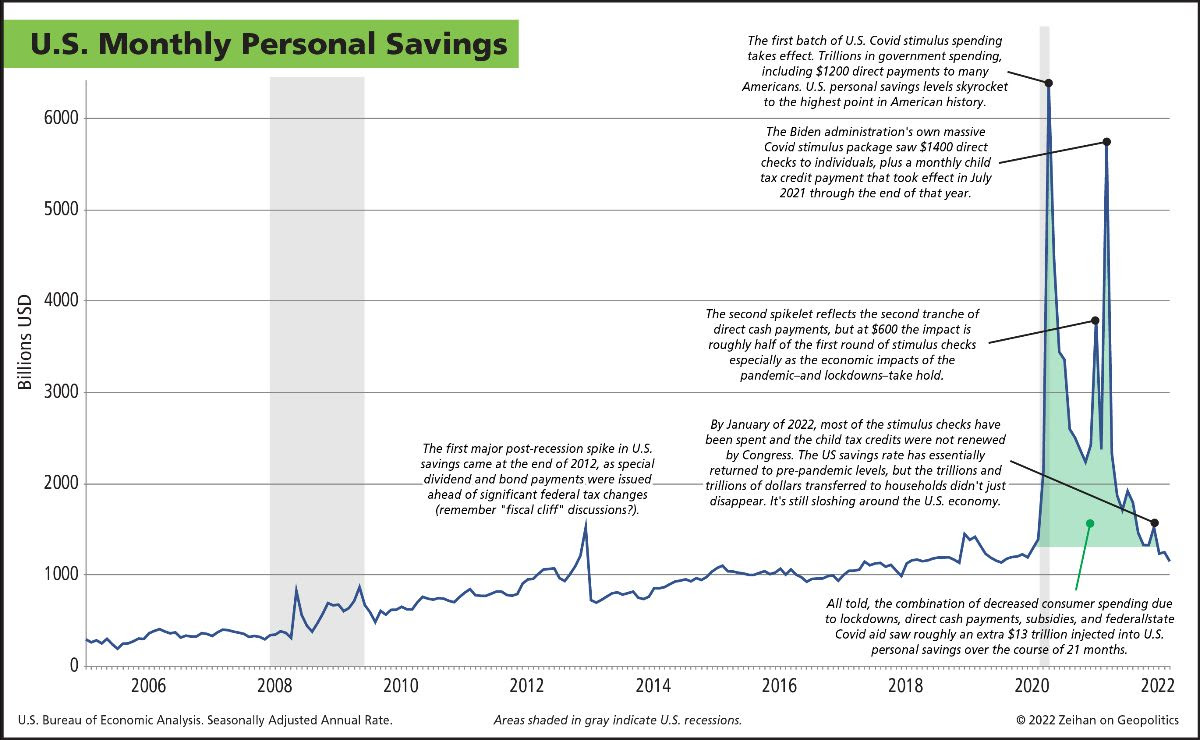

There’s also the stark reality of capital. Boomers have been earning and investing those earnings for decades. Boomer savings and their general high apetite for risk have seen a flood of capital spread into industries and environments across the world as the price of capital plummeted and its availability increased.

Not anymore. Boomers, like all retirees, favor safe, stable, long-term investments. As they switch from adding to their savings and investment accounts and instead transition to drawing from them in retirement, the Boomers are going to cause as big of a splash leaving the labor market as they did when they jumped in in the 80s..

Here at Zeihan On Geopolitics we select a single charity to sponsor. We have two criteria:

First, we look across the world and use our skill sets to identify where the needs are most acute. Second, we look for an institution with preexisting networks for both materials gathering and aid distribution. That way we know every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence. Then we give what we can.

Today, our chosen charity is a group called Medshare, which provides emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it. Until future notice, every cent we earn from every book we sell in every format through every retailer is going to Medshare’s Ukraine fund.

And then there’s you.

Our newsletters and videologues are not only free, they will always be free. We also will never share your contact information with anyone. All we ask is that if you find one of our releases in any way useful, that you make a donation to Medshare. Over one third of Ukraine’s pre-war population has either been forced from their homes, kidnapped and shipped to Russia, or is trying to survive in occupied lands. This is our way to help who we can. Please, join us.