The US needs to massively expand its ability to generate electricity. A possible solution? Mixed-oxide nuclear fuel. We’re talking repurposed weapons-grade plutonium mixed with uranium. This is complex, expensive, and time intensive. And perhaps more to the point, there’s a proliferation concern. No surprise that Russia is the only country that has done this so far…

Transcript

Hello. Peter Zeihan here. Coming to you from Colorado. Today we’re going to talk about an old technology that the Trump administration is dusting off and seeing if it’s applicable for the current environment. The reason is that the United States has just massive electricity shortages right now, and a number of states are on the verge of having, rolling brownouts.

And we’re not talking here about California. We’re talking about everybody. Trump administration says that it wants to massively expand manufacturing output. We can debate whether the policy that is in place is going to enact that. But I would argue that we need to expand, the industrial plant by at least double in order to prepare for a globalized world.

Most of the products that we’re used to importing, we’re gonna have to make ourselves one way or the other. Plenty of debate to happen about the specifics of Washington’s policy. But if any version of this is going to happen, we need more electricity. We probably need to expand the grid by about 50%.

And at the moment, pretty much all electricity expansions in the country are on hold. The Trump administration’s tariff policies have massively driven up the cost of doing everything that is related to the grid. For example, copper and aluminum, the two biggest inputs. And those now have a surplus tariff of 50%. And the government has actually canceled a number of power plants that it doesn’t like.

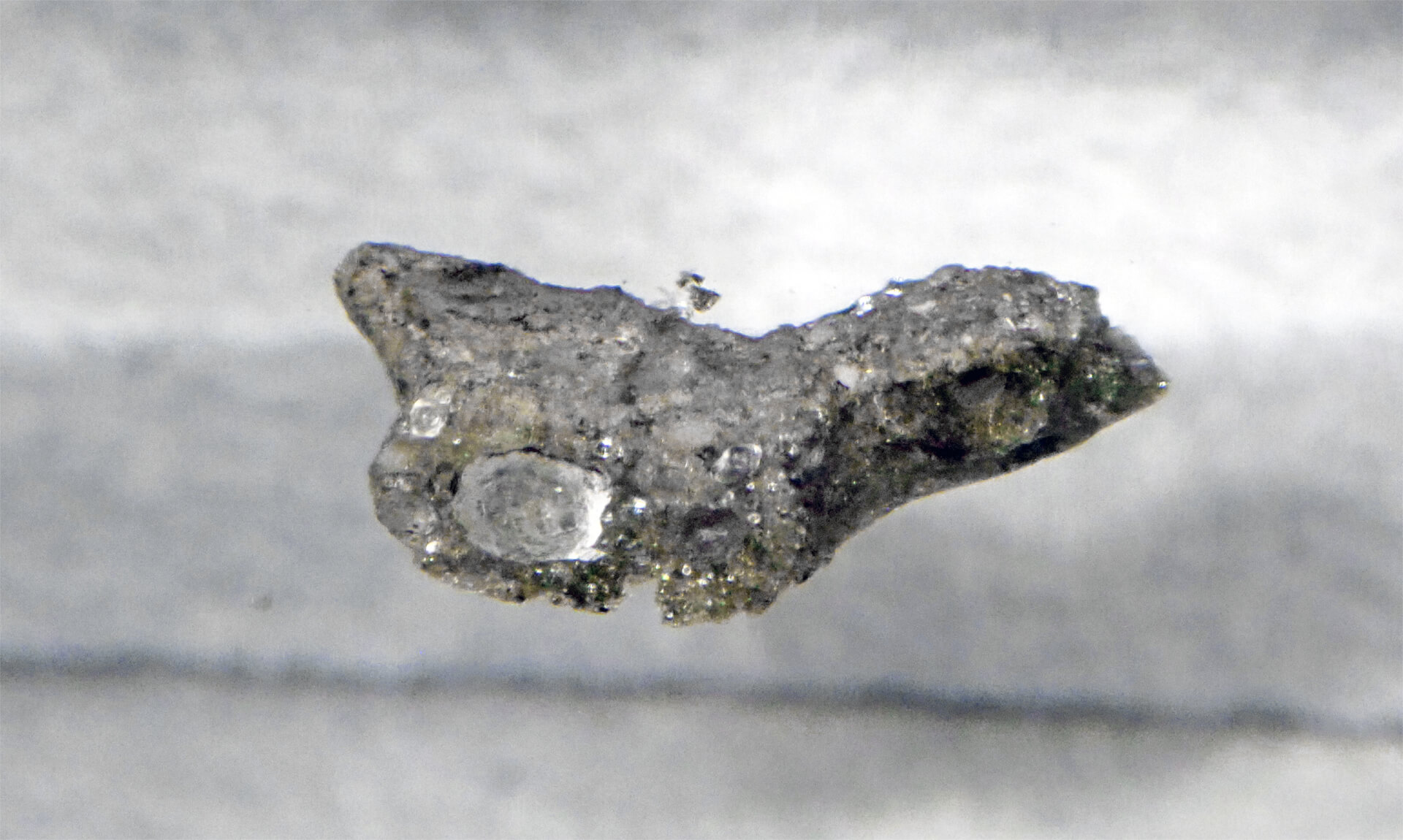

Because Donald Trump doesn’t like windmills. So the government, as a partner in the process of expanding the grid, has basically become a burden rather than a bolster. So this new technology, old technology, is something that maybe the government can actually step in, in a constructive way. And it’s called mixed oxide fuel. In essence, you modify a nuclear power reactor.

So instead of running on a down blended uranium, where, say, 3 to 5% of the uranium is a fissile component, in a broader block of power fuel, you instead use MOX, which is a mix of uranium and plutonium. Whether one technology is better or worse than the other from an economic point of view is very much in debate.

The only country that uses Mox at the moment for their civilian power systems is Russia. And Russia does it because it had 30,000 nuclear warheads, mostly plutonium driven, as part of its arsenal. When the Cold War ended. And they basically when they decommissioned them as part of arms control agreements, they took all of those warheads and spun them into the fuel.

So from their point of view, it’s a big savings. As a rule, once you factor in the cost of expanding or modifying your nuclear power system in order to use the MOX, it’s probably a wash for an economic point of view, because the up cost investment is so high. And if you’re going to use it just to use spent military, surplus equipment, eventually you’re going to run out of that.

You don’t have to have a plutonium supply chain. So a number of countries have played with this technology, most notably Britain, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Japan, also India. But no one has actually instituted as a civilian program. The problem is very simple. Not a lot of countries have nuclear weapons. Not a lot of countries had tens of thousands of them to decommission to serve as an input fuel source.

Really just the United States and Russia in that regard. Which means that if you want this to work, you have to build a civilian plutonium production system. Now, plutonium does not occur naturally in the world. It’s pretty much only generated as a byproduct of a, you guessed it, uranium power plant. One of the waste products that comes out of spent uranium based nuclear fuel is plutonium.

So if you want to have a MOX industry, first you have to have a uranium power plant industry, and then you have to have a system that takes the spent nuclear fuel and separates out the plutonium and purifies it. So basically, to have this sort of power sector, you have to have a civilian system that creates large volumes of weapons grade plutonium as part of their supply chains, which explains why most countries have not embraced it.

The Trump plan would do basically an echo of the Russian plan and take some plutonium cores from weapons that we have decommissioned and convert them to MOX. The problem they’re going to come across in addition to the proliferation question, is the same problem of everyone else who has decided to play this game. It’s a processing issue. You have to take the plutonium cores from the old decommissioned weapons, spin them into a different form in a different geometry.

it’s a manufacturing issue. It’s a fabrication. And above all, it’s a processing issue. And one of the problems the United States has at every level right now is we don’t have enough materials processing. We need to be able to turn bauxite into aluminum. We need to be able to turn iron ore into steel. We need to be able to turn copper ore into copper wire.

And if this program was going to work, would need to be able to turn surplus plutonium cores from decommissioned weapons into fuel. So it’s an interesting idea, but there’s a lot of upfront investment that has to be done before you can seriously try it.

They are hoping, hoping, hoping, hoping to have a little pilot program going by the end of calendar year 2026 to see if it’s even viable. I don’t know if it’s going to be viable, but as part of this process, you also then have to prepare a fuel cycle that puts weapons grade plutonium civilian hands on a regular basis.

And to this point, the only country in the world that have decided that that’s a good idea is Russia. And Russia, of course, is one of the world’s great proliferator.