If you’ve read my book The Absent Superpower, then today’s video shouldn’t come as a surprise to you (yes, I wrote it nearly ten years ago!). If you’ve been stuck under a rock and haven’t gotten the chance to read it -OR- you want a refresher, you can purchase a copy below.

You can even purchase an autographed copy as well here

Given the recent conflict in the Middle East, I’m worried that an oil crisis could be brewing. The main players that might kick off the (next) Gulf War are Iran, Israel and Saudi Arabia.

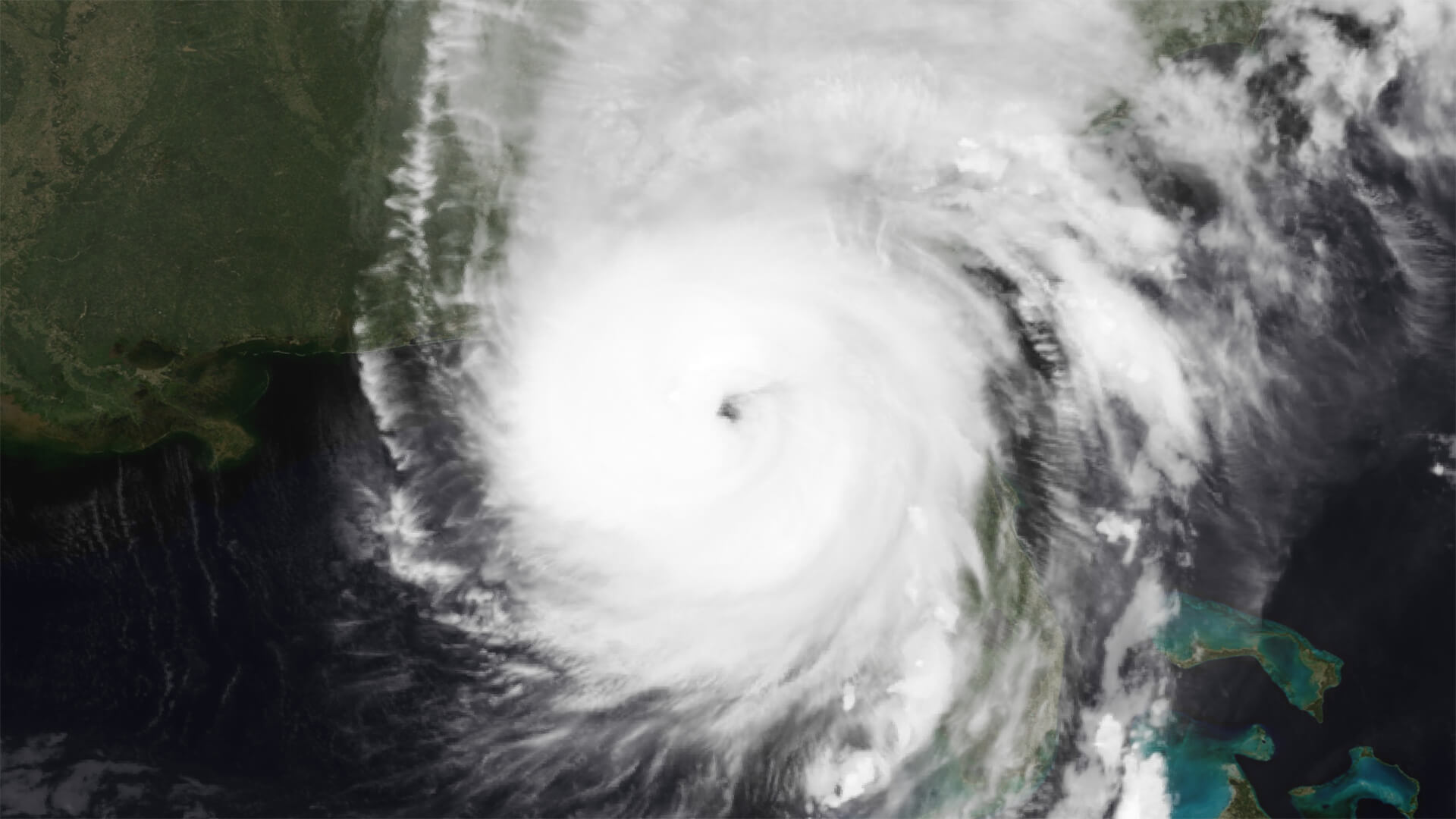

Israel was recently attacked by Iran and their retaliation could be devastating for Iran. Should they choose to target critical Iranian oil infrastructure – most of which is conveniently located near Kharg Island – Iran’s exports would plummet. Should that happen, an Iranian attack on Saudi oil fields wouldn’t be out of the question, and then we could be talking about 20 million barrels per day being under threat.

That means a global oil price of $300 per barrel is in the cards…but not for everyone. The US has the domestic supply to maintain a price closer to $60 per barrel (outside of California, because they still rely heavily on Persian Gulf imports). China would get the snot knocked out of ’em if it does play out like this. The UAE and Saudi Arabia would keep some exports alive thanks to pipelines that bypass the Strait.

Before you go buy a few drums of oil to throw in the basement, let’s wait for Israel to decide what their retaliation plan looks like.

Here at Zeihan on Geopolitics, our chosen charity partner is MedShare. They provide emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it, so we can be sure that every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence.

If you sign up for our Patreon page in the month of October, the proceeds from your subscription for the remainder of 2024 will be donated directly to MedShare. So, you can get our all of the perks of joining the Patreon AND support a good cause while you’re doing it.

We encourage you to sign up for the Patreon page at the link below.

Transcript

Hey, everybody. Peter Zeihan here, coming to you from the gloomy California coast. Got a nice little inversion layer going on out there. Anyway, today we’re going to talk about something that I haven’t really talked about in my professional career because I never thought it was going to happen until we had a change in circumstance. Well, we’ve had a change in circumstance, and now it’s time to talk about it.

And that is the possibility of a severe oil crisis because of a conflict in the Middle East. Now, back at my old job at Stratfor, they were always beating this drum. The idea that Iran was about to close the Strait of Hormuz and oil prices go to $500 and blah, blah, blah. And I was always the dissident voice because unless and until Iran feels it has no other choice, that doesn’t work because all of Iran’s crude goes out through the Strait of Hormuz.

Now, when I left, I went on my own. My second book, written about ten years—ten years ago, how did that happen?—mentions the three wars of the globalization period, conflicts that will boil up because the U.S. has stepped back, and whether the countries feel they have an opportunity or because they’re desperate, they take matters into their own hands.

Now, one of these I called the Twilight War, which is now in the opening act with the Ukraine conflict as the Russians try to reshape their neighborhood. But the second one, I called the Next Gulf War. And it’s about a conflict in which Iran and Saudi Arabia fight each other at each other’s throats because they can’t reliably get energy out.

So they try to take out each other. In that scenario, you basically have potentially 10 to 12 million barrels of crude that is at risk. Now, I haven’t brought this conflict up very much since I wrote the book because the circumstances haven’t warranted it. Especially in the last three years, it’s all been about Ukraine and Russia in their Twilight War.

But in recent days, I am reassessing. And specifically, the concern is after Iran launched a couple hundred missiles at Israel a couple weeks back, the Israelis have made it very clear that they intend to retaliate in the time and place of their own choosing. And they’ve specifically shortlisted Iran’s oil sector as potential targets. There is a very obvious target point.

It’s called Kharg Island. There is subsea infrastructure that links via pipe the mainland to the island. And then all, all, all of Iran’s offshore loading platforms are just off the island. This is the only meaningful export point for Iranian crude. And as the Israelis have proven, back in April when we had the previous Iranian assault on Israel, they can take out any air defense system in the country.

If you remember back then in Isfahan, which is where the Iranians have the nuclear program headquartered, the Israelis took out the air defense around the nuclear program specifically to prove that they could if they wanted to. So any sort of air defense and Kharg is almost a rounding error in the Israeli calculus. And there’s no bridge here. It was not built by the Iranians.

It was built by Westerners in the days before the Shah fell. So if Israel decides to move, it’ll just take a couple of sorties. They’ll be done in an hour. And Iran’s entire oil export capacity would be devastated. And in that scenario, suddenly Iran doesn’t have much to lose and, out of desperation, would probably make a push to take out Saudi Arabia.

The scenario specifically outlined in the book involves a military invasion that crosses into Iraq and Kuwait, heads south, making a beeline for the oil fields. Keep in mind that the southern half of Iraq is Shia-populated and has generally had a very pro-Iranian slant ever since the war against Saddam Hussein back in the 2000s. Whether or not it would be an easy invasion is open for debate based on how or whether other countries, such as the United States, get involved.

But even if that is not an option, all of those missiles that the Iranians launched recently against Israel, they have more than enough to take out oil export and processing facilities on the western side of the Persian Gulf, notably Saudi Arabia. Most of Saudi Arabia’s crude comes from the Ghawar region, which is hard up against the coast, and all of the loading platforms are also on the Gulf Coast.

Well, most of them. So you’re talking between the two of them, a significant reduction in what is globally available. If it was just Iran, not a big deal. You’re talking about a million barrels a day. They’ve been under sanction for a while. They’ve mismanaged their own system. But if you bring in Gulf states, most notably Saudi Arabia, all of a sudden that 1 million turns to 10 million or more, and that doesn’t count what comes out of, say, Iraq or the UAE or Kuwait, all of which would be in the way of a potential conflict.

So now you’re talking potentially 20 million barrels a day. You want oil prices above $300? That’s how you get there. Now, not everything is equal for all players. Yes, currently we have a single global oil price. But in that scenario, that system would shatter because in the United States we have a populist president, and the people running for president are populist.

And back in 2015, U.S. Congress granted the American presidency the authority to summarily end all American crude oil exports, which have been several million barrels a day for a while now. The shale revolution really is rocking and rolling. And so if we have oil prices shoot up, you would have the president, whoever it happened to be, end exports. That would create a super-saturated market within the United States while denying the rest of the world another few million barrels per day, sending prices up even higher.

So you’d have a functional ceiling in the United States of $60 to $70 a barrel, and you’d have a functional floor in the rest of the world, probably around $200 to $300 a barrel. So you get a global depression. At the same time, the United States just kind of skates right on. Second, the country that would suffer the most by far would be China.

It is the largest consumer of crude from Saudi Arabia, from the UAE, from Kuwait, from Iran. And all of those sources would be in danger in some way, if not going completely. Third, on the producer side, not everyone in the Persian Gulf would suffer equally because the Saudis and the Emiratis have seen some version of this problem coming.

And so both of them have built bypass pipelines that avoid the Strait of Hormuz completely. So roughly 5 million barrels a day, maybe as much as six and a half, could still get out. That’s enough to take a lot of the sting out from a budgetary point of view. And if you’re Saudi Arabia and oil prices triple but your exports halve, you’re actually in a net financial superior position.

Assuming the Iranians don’t conquer you. And then finally, in the United States, there is one state that would be in a different situation, and that would be here in California. California doesn’t have any pipes that connect it to the oil fields of Ohio or North Dakota or Texas. And it is the one oil producer in the country that has not benefited from the shale revolution because of regulation out of Sacramento, which means that in this scenario, they’d be kind of hosed because they actually import most of their crude from the same place the Chinese do—the Persian Gulf.

So in the rest of the country, you’ve got a ceiling on energy prices. But out here on the West Coast, you’re looking at $10 a gallon for gasoline, triggering a significant schism in the economic outcomes, even within one country. So this has gone from something that was just kind of out there in the future, if and when de-globalization really gets going, to all of a sudden it’s a meteor.

And now the chances it’s going to happen? Well, I mean, really that’s up to Israel. And then, of course, the Iranian reaction. But I would say it’s somewhere between 1 in 4 and 1 in 3 to happen over the course of the next few months. And considering the depth of this disruption, I hope everyone sleeps well.