It’s important to reflect from time to time, not only on where we have been right but where we have been wrong. With that, here is a repost from a newsletter originally published on December 29, 2021.

All anyone can talk about in Europe these days is Russia. Russia is constricting natural gas flows to Europe in order to drive energy prices higher and extract geopolitical concessions. Russia is using irregular state tools — think cyber — to manipulate European politics and exacerbate the COVID epidemic by planting misinformation about vaccines. Russia is threatening war in Ukraine, up to moving over one hundred thousand troops to the Ukrainian border region, and tapping the global mercenary community to recruit thousands of fighters to throw at Kiev. Russia is demanding the right to fundamentally rewrite the security policies of not only Ukraine, but Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Romania, Bulgaria, Slovenia, Croatia, Albania, Turkey and Germany in exchange for a de-escalation in Ukraine.

I’m down on paper and video saying that Russia’s impending doom (more on that in a minute) will force it to take a more aggressive security posture, specifically on Ukraine. Today much of Russia’s border regions are indefensible. There are few geographic barriers to block potential invasion, forcing the Russians with their dwindling numbers to attempt to defend massive stretches of territory. What barriers the Russians do have — Crimea and the Caucasus come to mind — are only because of the sort of strategic adventurism that Putin is now threatening to Ukraine as a whole. There is a method to the madness. To paraphrase Catherine the Great, Russia can expand, or Russia can die.

But a few things have changed since I laid out my position in The Accidental Superpower back in 2014 and sketched out the general outlines of the hypothetical Twilight War in The Absent Superpower in 2017.

First big change: Ukrainian politics and identity.

Back in the 2000s, Ukraine could be very charitably called “messy.” It was an oligarch playground, sharply divided into three competing regions. The biggest region in the east was populated by either Ukrainians who spoke Russian as their first language, or actual Russians who due to the quirks of history happened to live on the Ukrainian side of the dotted line on the map. Ukraine has always been home to the greatest concentration and number of ethnic Russians outside of Russia’s borders. And these groups — both the ethnic Russians and the Russian-speaking Ukrainians — were unapologetically pro-Moscow.

It was the mix of this pro-Russian sentiment with the Kremlin’s view that large-scale political violence is often useful, that set us onto the path to where we are today. In early 2014 then-Ukrainian president Victor Yanukovych — one of those pro-Russian Ukrainians — dealt with pro-Western “Euromaidan” protesters by using Ukrainian special forces to shoot up a couple thousand people. He was driven out of office and ultimately out of country and now he is living in exile in, you guessed it, Russia.

Yanukovych’s actions against his own people — actions publicly supported by none other than Vladimir Putin — started Ukraine down the road to something I had once dismissed out of hand: political consolidation and the formation of a strong Ukrainian identity. Putin didn’t — hasn’t — figured that out. Later Russian actions — starving the Ukrainians of fuel, annexing Crimea, invading the southeastern Ukrainian provinces of Donetsk and Luhansk in the Donbas War — only deepened the Ukrainian political consolidation that Yanukovych inadvertently started.

Far from capitalizing on strong and legitimate pro-Russian sentiment, Russia’s policies towards Ukraine these past seven years have turned even the most pro-Moscow Russian citizens of Ukraine into Ukrainian nationalists.

In 2010, Ukraine was not a country. It was simply a buffer territory between Russia and the European Union with no real identity, and it would have been ridiculous to admit such a non-entity into either the EU or NATO. Today Ukraine is a country, and the idea of EU or NATO membership isn’t nearly so crazy. And that evolution is all because of Putin’s ongoing miscalculations.

Second big point: military reality.

Back in 2014 when the Russians launched the Donbas War, Putin boasted that should he choose, Russian forces could easily invade Ukraine. He noted Russian troops could be in Kiev in under a month.

It may have been a brag, but it most definitely was neither a bluff nor an exaggeration. The Russian military may be a pale shadow of its Soviet forebearer, but it is far better than the war machine which ground to humiliation in Chechnya in the 1990s. Ukraine’s military in comparison? Phbbbbt. Wracked by corruption, enervated by a lack of motivation, armed with nothing more than the pre-1992 equipment that the Russians chose to leave behind when the Soviet Union fell? There’s a reason Yanukovych used the special forces to suppress the Euromaidan protestors. The military wasn’t even up to that job. Fighting a hundred thousand or so Russian troops? That’s funny.

Since 2014, some things have gotten better. Western assistance has helped professionalize the forces. The Russian invasion has charged Ukrainian commanders some high tuition at the school of Real-Life War. Strengthening national identity has improved force cohesion. But the biggest shift is in weaponry.

Arming a country the size of Ukraine with sufficient military equipment to fight the Russians solider-to-solider would be a Heraclean effort. So that’s not what the United States has done. The Americans have provided the Ukrainians with Javelin anti-tank missiles. Javelins are man-portable and shoulder-launched, weighing in at under 50 pounds. They shoot high and plunge down, striking tanks on the top where armor is weakest. And above all, they are sooooo eeeasy to operate. If you can make it to level 3 on Candy Crush, you can use a Javelin.

Considering any drive to Kiev will be a tank operation, giving Javelins to the Ukrainians is like giving water to firefighters. It’s the perfect tool for the job. The Javelins made their wartime debut on the front lines in Donbas only in November 2021…about when the Kremlin started getting all screechy and demanding wholesale changes to European security alignments. Coincidence? I think not.

Now don’t get carried away. I’ve little doubt that Javelins would be enough should the Russians get truly serious. Any Russian invasion force would massively outnumber and outgun the defenders. But that’s not the point. Unlike in the 2000s or in the Donbas War, the Ukrainians can now slip a knife through the chinks in the Russians’ armor and make them bleed. A lot. And unlike in the 2000s, the Ukrainians now have a national identity to rally around and fight for. The Ukrainians now have the means and motive. It’s up to the Russians to decide if they’d like to provide the opportunity.

If war comes, the Russians could still reach Kiev. But it would likely take three months instead of one. The Russians could still conquer all of Ukraine. But it would likely take over year rather than less than three months. The toll on the invaders would be high and most of all the war would only be the beginning. After “victory” the Russians would have to occupy a country of 45 million people.

Which brings us to the final bit of this story: demographics.

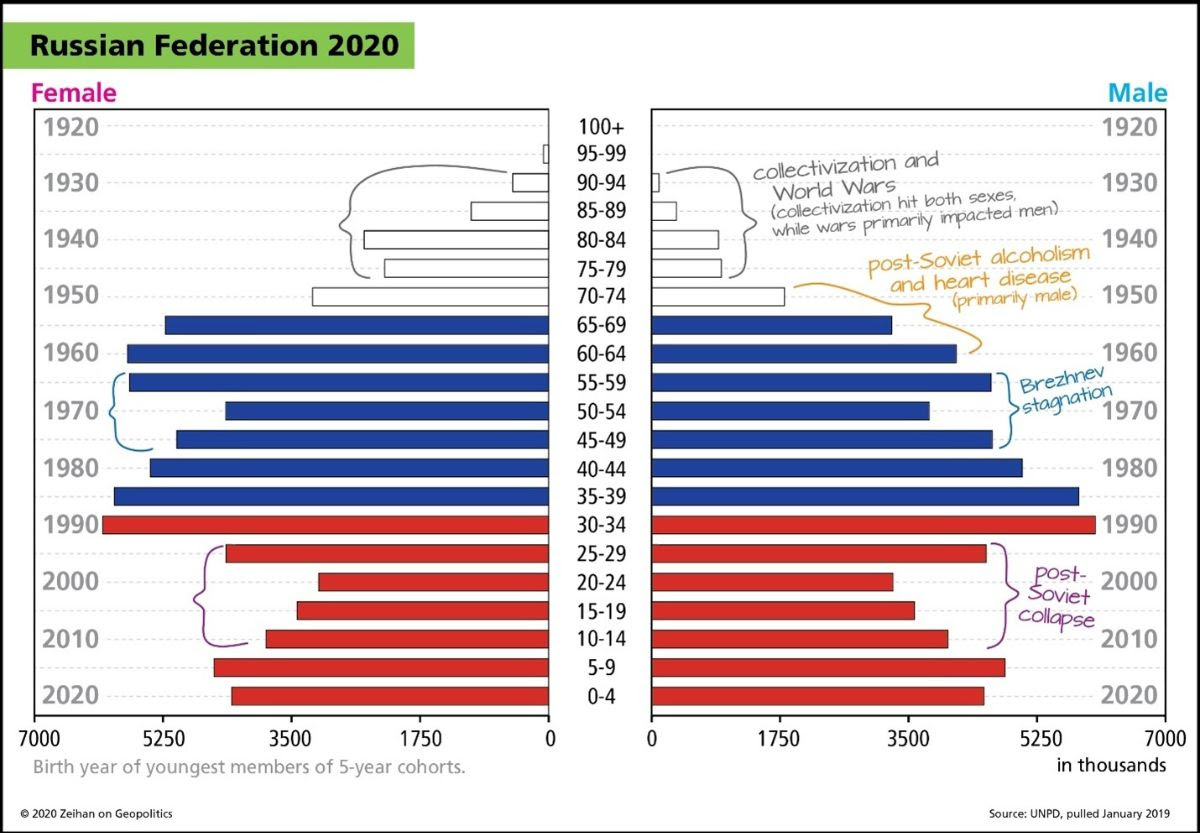

Russia’s had a rough time of…everything. The purges of Lenin and Stalin. The World Wars. The post-Soviet collapse. Horrific mismanagement under Khrushchev and Brezhnev and Yeltsin. Sometimes in endless waves, sometimes in searing moments, the Russian birthrate has taken hit after hit after hit to the point that the Russian ethnicity itself is no longer in danger of dying out, it is dying out. And for this particular moment in time, there just aren’t many teens today to fill out the ranks of the Russian military tomorrow.

The implications of that fact are legion.

Least importantly, if somewhat amusingly, is the Russians are now flat-out falsifying their demographic data so the situation does not look so…doomed. Check out the bottom two age categories in the above graphic; the section for children 10 and under. A few years ago the Russians started inflating this data. Best guess is there are probably one-quarter to one-third fewer children in Russian than this data suggests. That’s roughly a four million child exaggeration.

Most importantly are the implications for a potential Russian-Ukrainian War. Any Russian solider lost anywhere cannot be replaced. If Putin commits to an invasion of Ukraine, Russia will win. But the cost will not be minor. The war and occupation will be expensive and bloody and most importantly for the world writ large, it will expend what’s left of the Russian youth.

Will Putin order an attack? Dunno. There was a demographic and strategic moment a few years ago when the Russians could have conquered Ukraine easily. That moment is gone and will not return. But the strategic argument that a Russia that cannot consolidate its borders is one that dies faster remains.

Perhaps the biggest change in recent years is this: the United States now has an interest in a Russian assault because it would be Russia’s last war.

Demographics have told us for 30 years that the United States will not only outlive Russia, but do so easily. The question has always been how to manage Russia’s decline with an eye towards avoiding gross destruction. A Russian-Ukrainian war would keep the bulk of the Russian army bottled up in an occupation that would be equal parts desperate and narcissistic and protracted until such time that Russia’s terminal demography transforms that army into a powerless husk. And all that would transpire on a patch of territory in which the United States has minimal strategic interests.

That’s rough for the Ukrainians, but from the American point of view, it is difficult to imagine a better, more thorough, and above all safer way for Russia to commit suicide.

Here at Zeihan On Geopolitics we select a single charity to sponsor. We have two criteria:

First, we look across the world and use our skill sets to identify where the needs are most acute. Second, we look for an institution with preexisting networks for both materials gathering and aid distribution. That way we know every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence. Then we give what we can.

Today, our chosen charity is a group called Medshare, which provides emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it. Until future notice, every cent we earn from every book we sell in every format through every retailer is going to Medshare’s Ukraine fund.

And then there’s you.

Our newsletters and videologues are not only free, they will always be free. We also will never share your contact information with anyone. All we ask is that if you find one of our releases in any way useful, that you make a donation to Medshare. Over one third of Ukraine’s pre-war population has either been forced from their homes, kidnapped and shipped to Russia, or is trying to survive in occupied lands. This is our way to help who we can. Please, join us.