Hong Kong has been one of the most important economic locations on the planet for over a century.

China has always had problems holding together, but it has also always been a land of opportunity for outsiders who held a logistical and technological edge. Few powers in history have held a sharper edge than the British Empire. Hong Kong sits at the mouth of the Pearl River Delta, and in dominating HK the Brits were able to exploit the cheap labor of the lower basin, while also controlling any exports from the broader Pearl. It was a strategy the Brits had used to great success in locations as diverse as Suez, Calais, the Gambia, Durban, Charleston, and New York City.

As Mao’s de facto alliance with the Americans took form in the 1970s, British Hong Kong became internationalized. The Hong Kongers would use foreign tech and capital – repeating a pattern that stretched back literally a millennium – to create products for export.

In the late 1980s then-British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher negotiated the transfer of Hong Kong to the Chinese mainland and a new chapter began. Hong Kong shifted from being a manufacturing base to being a financial and logistical hub. The same foreign tech and cash came in, but HK used its already-sophisticated managerial skills to funnel it into the lower Pearl.

That’s the economics. Here’s the politics:

It is not an oversimplification to say the Chinese Communist Party is obsessed with national unity. The “country” of China has historically not held together well, and Hong Kong was no exception. For most of Chinese history, the southern coastal cities from Shanghai south to Hong Kong were integrated more with the wider world than with their own countrymen. But with the Order’s advance in the late 1940s, the imperial age ended and Maoist China was able to establish control over the entire coast… aside from Hong Kong. The handover from London to Beijing in the 1990s brought Hong Kong into the fold as well.

But there was a poison pill.

The British ran Hong Kong like the imperial territory it was. While the Americans forced the Brits to divest nearly all their empire, the Americans made an exception when it came to Hong Kong. It would have been ludicrous to squander the intelligence opportunities of having British control of such a rich and strategically located bit of allied territory. But when it became obvious to Thatcher that handover was inevitable, the Brits started democratizing Hong Kong. In the aftermath of the June 1989 Tiananmen massacre, the effort intensified. When the handover finally occurred in July 1997, Hong Kong was a full-fledged democracy (albeit one who obviously had no say as to which country it would be associated with).

Thatcher hardwired into the handover treaty a looooong political transition period. While Hong Kong would immediately and officially become “Chinese” territory in 1997, its political system would remain largely self-governing for another half-century. An island of democracy in a sea of authoritarianism. The Chinese call it One Nation, Two Systems.

Say what you will about Thatcher, she was very good at monkeywrenches.

So long as the Chinese economy performed well, Two Systems was an annoyance Beijing was willing to tolerate. But things have changed:

First, the Chinese export-led system has peaked. Global demographics have turned negative and global consumption can no longer absorb exports on the scale China can churn out.

Second, the Chinese financial system is in dire straits. Lending in China isn’t like lending in most places where you… well… have to pay back the loan. In China the government banks funnel cheap credit to firms who guarantee high employment, and to hell with profitability. The goal is to keep everyone in a job so they don’t protest. A side effect of this policy generates scads of subpar quality products that no one needs. China then dumps those products on the international market. Not only can the global market no longer absorb all the Chinese stuff, the financial model has pushed to the point that there are so many debt bombs on the foundations of so many sub-sectors that it would make the bad actors of the US financial crisis blush.

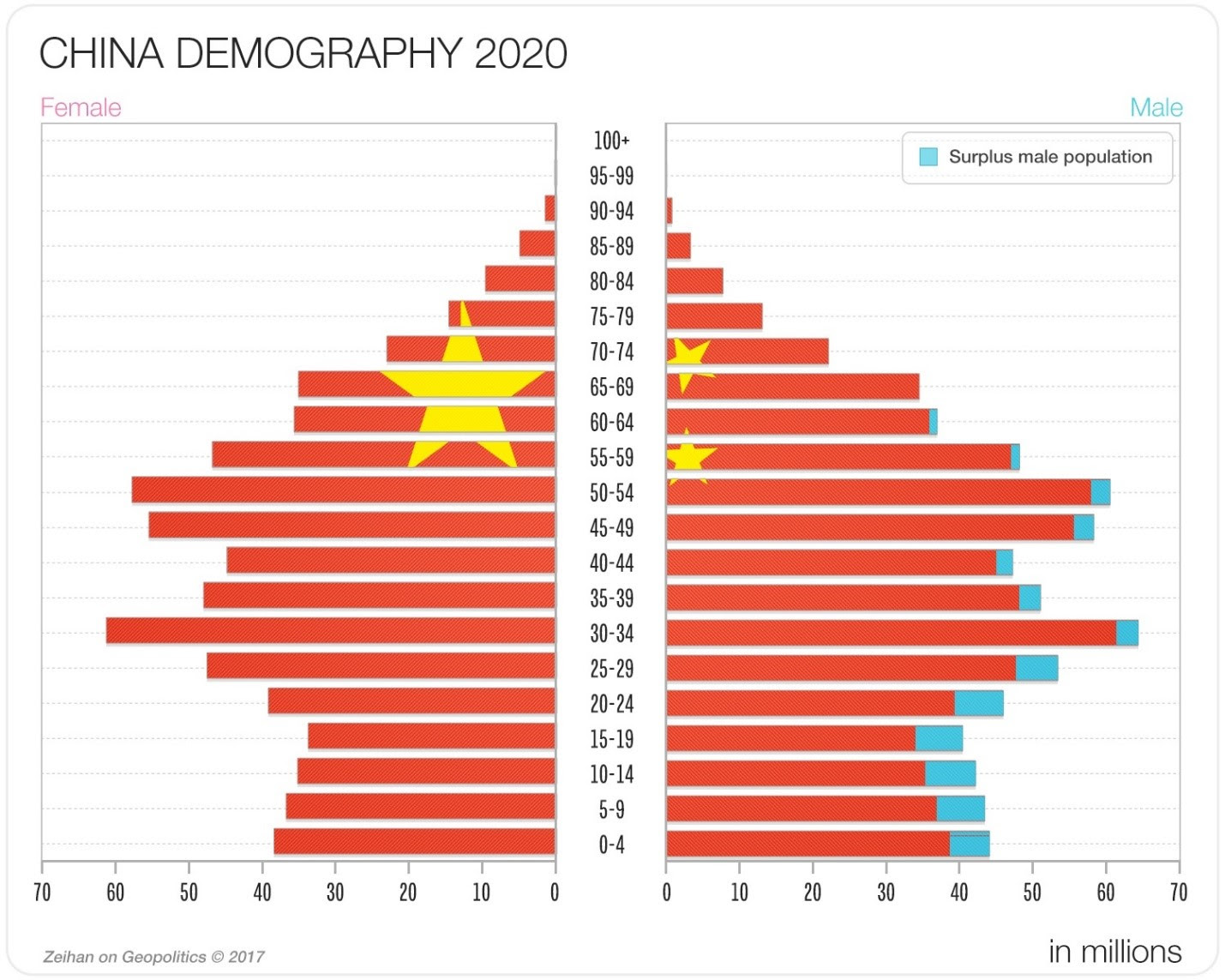

Third, Chinese demographics have peaked. Replacing global demand with Chinese demand was never really an option, and in 2019 it became obvious that Chinese demand was plateauing. Automotive sales – typically the purest indicator of customer demand – have dropped more than most countries do during heavy recessions. Blame the One Child policy – China is running out of twentysomethings. That’s driving labor costs up at the same time it is driving consumption down.

Fourth, the friendly geopolitical environment that China has thrived under – that all-important American-led Order – is in its final days. Much of what has brought China rapid economic development – foreign technology and capital, bottomless global markets, endless raw material imports – is ending. With local markets insufficient to replace global markets, the Chinese hold an economy designed for the 1990s that has no place in today’s world.

Fifth, the Americans are formally and directly targeting Chinese industrial and trade policy. U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer has already dusted off plans to triple the total American tariff load on China as soon as he gets the go-ahead from his boss. There may be a bit of an American-Chinese trade truce in place, but I doubt it will last much longer than the last two (which each lasted about 75 days).

Sixth, an oil crisis is brewing in the Persian Gulf. Should the Americans do anything to impinge upon Persian Gulf oil flows – and “anything” includes leaving – China faces an energy crisis far worse than what the Americans struggled through in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Some two-thirds of China’s oil is imported, with over half of that coming from the Gulf. China’s navy is utterly incapable of convoying what it needs should convoys become necessary.

The Chinese leadership is fully aware of all these concerns and is fully aware that the Chinese ship of state can no longer sail in its current direction. President Xi Jinping – rightly – fears for the future of the unified Chinese state. To that end Xi spent the bulk of his six years in office to date eliminating anyone in the Communist Party who was willing to defy him under the guise of an anti-corruption purge. The effort was done with more than a bit of side-eye to smashing any sort of regional autonomy. Now’s he’s working on new tech-heavy programs designed to purge dissent throughout wider society. The jury is still out on how successful that will be, but it points to the it’s-not-paranoia-if-they’re-really-out-to-get-you feel of the Party at the moment.

Enter the Hong Kong protests of recent weeks.

Part and parcel to Xi’s efforts to preserve national unity is to lock down Hong Kong. In partial violation of the Two Systems policy, Xi pushed an “extradition law” on the Hong Kong government which would enable any mainland Chinese judicial entity – all of which are arms of the Chinese Communist Party – to issue arrest warrants for any Hong Kong citizen. China’s security services already kidnap Hong Kongers and smuggle them back to the mainland as they need to, but with the new law any local magistrate could force the abduction of anyone in broad daylight. (Such legal authority already exists within mainland China for everyone else.)

The Hong Kongers, realizing the extradition law’s adoption would mean the end of their special status some three decades early, have resisted. And protested.

The timing is far from coincidental. Beijing is ratcheting down on Hong Kong because it fears for the unity of the Chinese state as a whole. Hong Kong is resisting because it doesn’t want to be part of the Chinese state. The primary rationale for Xi’s new law is to keep the country together. The Hong Kongers’ rebellion is largely because of the new law. And now the phrase “Hong Kong is not China” keeps popping up in the protests.

Something’s gotta give, and it isn’t going to be Beijing.

The question, as it seems to be with everything, is timing. Much of the Chinese government’s actions these days – as regards Trump and trade talks, or Japan and territorial disputes, or Iran and oil – seems to be about buying time, but that time may be running out. On July 1, a group of Hong Kong protestors stormed the local legislative assembly with a degree of intensity that was new for the protests. This was less families-with-children-in-strollers and more clubs-and-pipes-of-the-Antifa-type. In the aftermath some of the graffiti caught my attention: “It was you who told me peaceful marches did not work.”

I don’t have the insight to know who spawned this particular action of vandalism.

Was it the leaders of what have so far been a hyper-organized protest movement? Are they testing the waters for a new push?

Was it some imported anarchists who just love a good riot?

Was it a false flag operation launched from the mainland to justify a crackdown?

Was Beijing aware the storming was imminent, and yet did nothing so that the radicals would provide a justification for their own destruction?

I don’t know. And unfortunately, it doesn’t really matter. Whoever thought that ransacking the assembly building was a good idea has crossed the Rubicon. Whether you view the true power in China as President Xi, the government in Beijing, or the Chinese Communist Party, it cannot tolerate this sort of action in Hong Kong – especially at this time. No matter what your view of Chinese history is, no matter what your view on Xi’s personal vindictiveness might be, the Hong Kong protests have become a threat to national unity. A new crackdown is imminent.

The scale of what’s about to happen is difficult to grasp:

At their peak, the Tiananmen protests involved 300,000 people, mostly students. The Chinese government sent in nearly as many troops to crush the movement. Fatality reports varied wildly from zero (the number Beijing proffered) to 10,000 (the estimate of the British embassy).

In Hong Kong, the protestors have regularly managed to get a million people out in the streets, a figure that has swelled to two million on several occasions. They aren’t just young people. They are families. Retirees. Bankers. Lots of people who normally never protest. I’ve not seen anything like this since the broad-spectrum Iranian protests that dislodged the Shah back in 1979. It is a huge proportion of Hong Kong’s total population (less than 7.5 million).

Ending the protests means nothing less than a full military invasion and occupation of the island. And unlike the Tiananmen massacre where reports of the military operation made it out piecemeal, in today’s social media age Hong Kong’s fall will be broadcast live for the world to see. It will be like Japan’s 2001 Sendai earthquake, but with a wall of tanks instead of a wall of water.

This all feels… momentous but I can’t quite put my finger on the implications. I’m a context guy and for this I just don’t have any. I cannot think of a military crackdown in a first-world economy in modern times. In the United States the last one was the Kent State shooting in 1970, but that was only a few hundred students and 67 bullets. Paris in 1968 got pretty messy, but the violence there was…what, threeorders of magnitude less than what’s imminent in Hong Kong. I’ve got to go back to the riots in Europe in the 1930s at the height of the Depression. The norms of our age are breaking apart and we’ve not yet developed the frames of reference to process what’s coming.

For the immediate future, the bottom line is that while Hong Kong lacks the size and reach and means to export its protest movement to the mainland, the CCP certainly has the size and reach and means to export its forces to Hong Kong. China’s information control systems are sufficient – and the grip of the CCP strong enough – to prevent meaningful contamination of the mainland political system. The protests will not only fail, they signal the end of Hong Kong.

Hong Kong is about to become an absolutely horrible place to be. The degree of Chinese… reconstruction of the island will be on par with the cultural genocide already being imposed upon the Uyghurs of China’s western Xinjiang region. It won’t last a week or a month or a year. We’re looking at something that will last at least a decade.

That will have deep implications for anyone doing business in the country.

At a minimum every ongoing reservation about operating in China is about to get a hard underline. Foreign business magnates like Tim Cook have so far been able to ignore the ethical implications of their firms’ China dependency. It is difficult to see that continuing in light of what’s about to occur.

And it isn’t simply about ethics. Many of the financiers that make Hong Kong work are Chinese citizens. Whether Bank of America or whoever is willing to stay in a place where their workers disappear is… questionable. But it doesn’t end there. It’s not just Chinese citizens; the extradition law also applies to foreigners. These companies are used to working in China, so it’s not that the Chinese system is so scary that they can’t stomach the country. It’s that none of these companies have tried to operate in China during an active crackdown.

The coming violence and occupation will utterly remove Hong Kong from the global network of logistical and financial hubs. Hong Kong has been China’s primary entry point, China’s primary export point, and most capable financial center. Its end takes the gem out of the Chinese crown, as it were. For the past thirty years, China has provided foreign investors with scale, cheap labor, security and local expertise. The ending of Hong Kong damages all that and more.