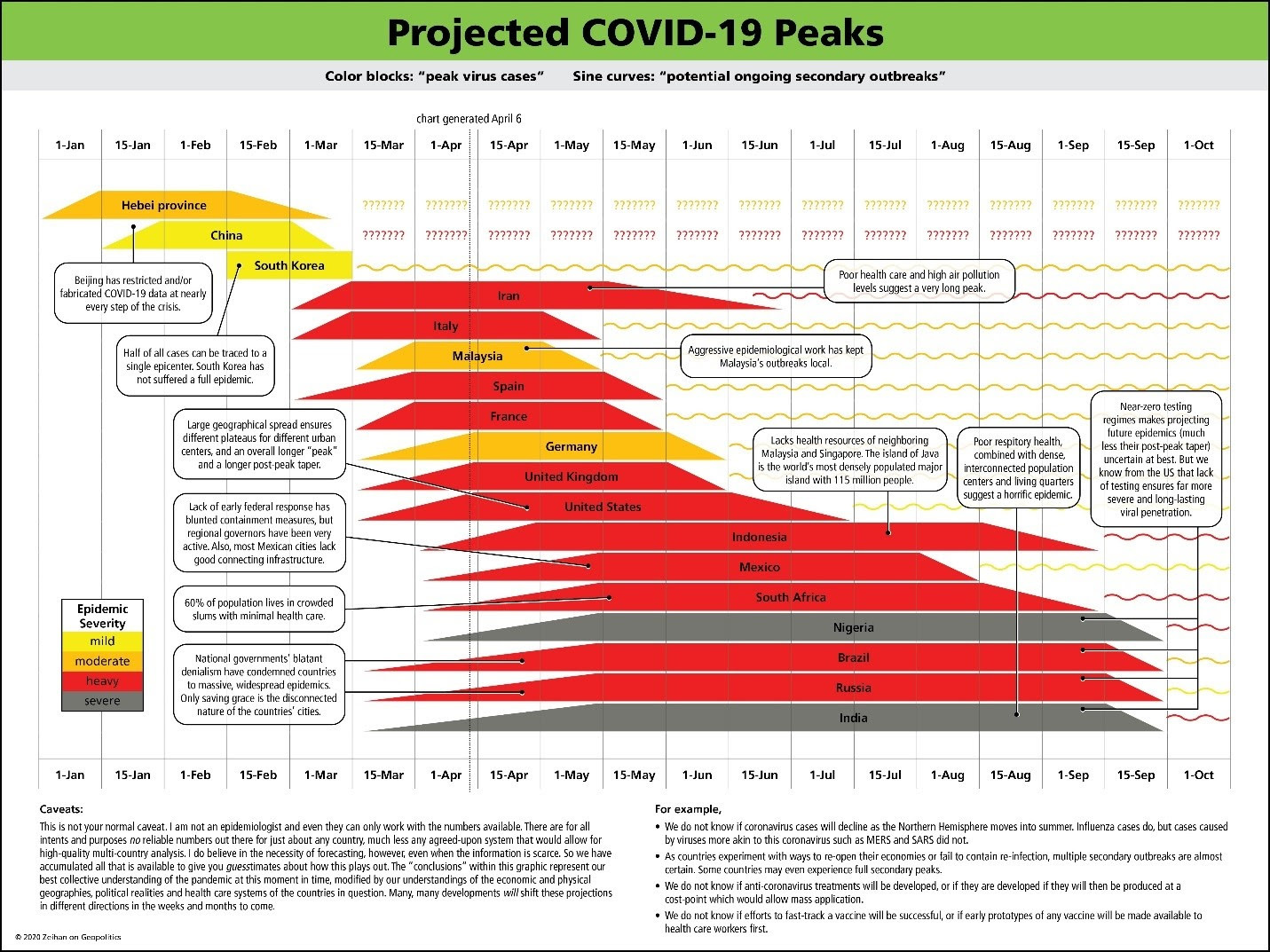

Folks, coronavirus is going to be with us for awhile, and it isn’t going to hit every country the same.

While all eyes are on New York City right now, it is only at the leading edge of the epidemic in the United States. Each metro region is going to experience its own peak and plateau in COVID-19 cases. NYC’s “peak” will hopefully be this week (but it may be a month from now) along with New Orleans and Detroit. Then other cities. The slapdash and erratic nature of the American lockdown, combined with a woefully insufficient testing system and America’s huge geographic spread, ensures that America’s coronavirus peaks and plateaus will not line up, and as such, occur over a much longer period of time.

The damage in the developing world is certain to be far worse. More densely populated cities defined by more cramped living conditions make social distancing difficult to impossible. Even worse, most of the developing world’s workers do not have jobs that enable telecommuting nor do the developing world’s governments have the raw fiscal power of the United States to simply send everyone home for a few weeks. People have to work, and they likely have to work in economic sectors where they most directly interact with one another in specific places. All that encourages both coronavirus’ spread and its ability to treat the poorest parts of the developing world as reservoirs.

Don’t see cases in the developed world yet? That’s no surprise. The virus started spreading there after most of the developed world so the epidemics are still early. Most of the developed world lacks high levels of air travel or between-city mass transit, slowing the virus’ spread. In addition, the very weakness of health systems in the developing world that will make the epidemic more painful also means there is hardly any testing.

Combine a longer American economic shut-off with pending deeper epidemics in the developing world than what we have seen thus far, and the end result will be a global economic system that both splinters and faces a very long period of subdued activity.

This hits every economic sector in some way, but arguably the industry which will suffer the most rapid and catastrophic change will be energy. Before 2020, the greatest global oil demand drop was only 10%, at the height of the 1998 Asian Financial Crisis. As a result, oil prices plunged by three-quarters. So far in the coronavirus crisis, global oil demand is down between 15% and 35%. Unlike in 1998 when low energy prices stimulated energy demand and so prompted its own recovery, this time we have months of large sections of the world simply remaining offline.

Not every producer is going to survive this. In fact, the global nature of the energy sector isn’t likely to survive this.

Join Peter Zeihan for a videoconference April 10 to explore which countries will fall out of the market, which will make the cut, and how the changed map of production will remake consumption patterns in the post-COVID era.

Future planned invents include:

- The Shattering of Global Oil (April 10)

- Agriculture

- Transport and Supply Chains

- Manufacturing

- Industrial Commodities