We’re looking at some global economic growth patterns today. Unfortunately, we’re entering an era with a lot of unknowns. Between collapsing demographics and industrial challenges, there seems to be more countries in the red than the green.

China is probably the worst off. After rapid growth brought on by urbanization, a large working-age population, and heavy subsidies, their growth has stagnated, and its population is getting more and more top heavy. Without a reversal of these trends, China’s economy is buying a one-way ticket on the struggle bus.

Even advanced economies like those in Europe are feeling the heat. As countries like Germany and Italy face their own demographic issues, new economic models will need to be created to keep their heads above water. Developing nations are a bit behind the curve in terms of aging demographics and industrial buildout, but they’ll need to shift towards higher value industries to ward off economic stagnation. Places like Brazil will also have to deal with China’s predatory industrial policies which have hindered economic progress.

So, it’s not looking great overall. Aging populations and an inability to evolve economically will stall growth in many regions. If these countries cannot navigate industrial transitions, global economic stability is going to look pretty bleak.

Here at Zeihan on Geopolitics, our chosen charity partner is MedShare. They provide emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it, so we can be sure that every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence.

For those who would like to donate directly to MedShare or to learn more about their efforts, you can click this link.

Transcript

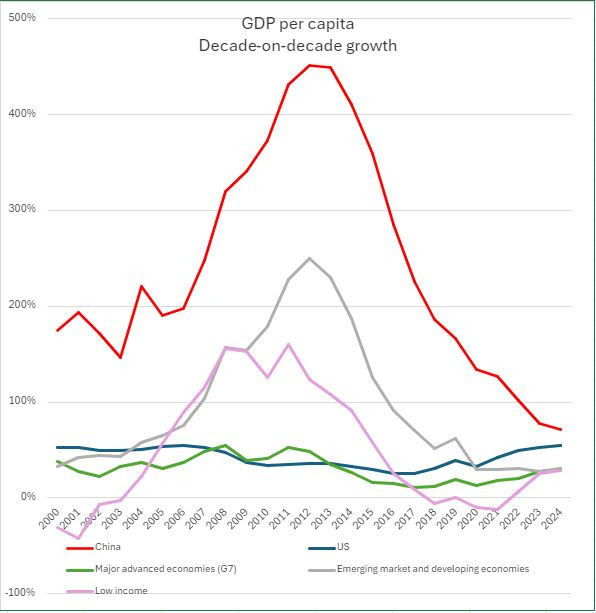

Hey, everybody. Peter Zeihan here. Coming to you from a chilly, foggy Colorado morning. Today we’re going to talk about growth patterns and what it holds for economic growth, for the world, for the future. Take a look at this chart here. Now this is annual change in GDP from a decade earlier. So you’re getting all the long term trends in one graphic.

The first country, of course, have to deal with is China because it’s such an outlier. China has two stories going on. Three stories, number one, they lie about a lot of their data. So, it’s probably not as good as it sounds. It’s probably at least a third. Less. Maybe half. Anyway, it’s still the fastest growth over the last 50 years in the world.

And that requires some explanation.

Two things going on besides the the line. Number one, the one child policy and rapid urbanization, landed, China with a much, much lower birth rate. In fact, it’s been higher in the United States since the early 90s. Now, in the long term, I have no secret that I think this is going to be the end of not just the Chinese state, but the Chinese nation.

The actual hunt of necessity is going to vanish from the world by the end of this century. But in the meantime, when you have a lot of people in their 20s and 30s and early 40s, but no kids and not a lot of retirees, every bit of energy can be focused on a combination of industrial production and consumption, which are the two primary methods for growing GDP.

And if you have that at the same time that you are also subsidizing the hell out of your industry, so you have a lot of investment led production. Yes, you do get growth and yes, it is robust. And yes, it’s such records, but it also sets the stage for the second problem, which is why that chart has just collapsed on the right side and that is that one.

Those people in their 20s, in their 30s and the early 40s become in their 40s, their 50s and their early 60s. Then that growth story is over, and you no longer have the workforce that is necessary to keep the activity going. And then all that’s left is exports and investment and that’s where the Chinese were about ten, 15 years ago.

Well, now in the late 2020s and moving into the 2030s, the people who are in their 40s, 50s and early 60s move on to their late 50s, 60s and early 70s. And then it’s just over. We’re already in a situation where the Chinese have about the same amount of population, and people over age 50 is under age 50.

This is already a terminal demographic. You just can’t get people in their 60s to kick out kids. But it does also mean that unless, unless, unless, unless the Chinese can wildly automate and retain access to every remaining consumer market in the world, that they are almost done. And we’re seeing that in the data. Now, the second story is what’s going on in the advanced world, most notably, Europe.

And that’s a demographic story, kind of like China. Now the Europeans have a much longer trajectory of history and economic policy than China. Really, China didn’t get started until the opening in 1980. Whereas the Europeans have been part of the industrial process for a century and a half. And so you had more well rounded growth. But the demographic story after World War Two was the same people urbanize, and they industrialize and they had fewer kids.

And you play that for 2 or 3 generations and there just isn’t a replacement generation. So just as with China, the Germans and the Italians have a lot more people over age 50 than they do under 50. In fact, they’ve been there for a decade already. And this is the decade where they start having more people over 60 than under 60.

And that is a very different economic model that we have yet to invent. And it’s difficult to see how it will have any growth at all. So as modern economies, a lot of the advanced world is simply fading away and, fading with ever increasing rapidity. That leaves the developing world minus China, which is a different story. When you apply industrial technologies like asphalt and concrete and steel and rebar and electricity, you get a huge amount of growth because you’re basically introducing a fundamentally new economic model on top of whatever your pre-industrial system was.

And in the building of that structure and the growth that you get from those structures, obviously your GDP rises quite a bit. But then the question is whether or not you can adapt to a new era. So what happened here in the United States is we did this much more slowly, but as we applied these technologies, we didn’t simply increase our production of raw and processed materials.

We also got into higher value added manufacturing and ultimately services. In most of the developing world, they have not been able, or at least not yet, to successfully make that transition. They’re still, for the most part, raw commodity economies. And so even when you industrialize but don’t change your underlying economic fabric, you get a really good burst of growth for 20, 30 years.

And then it just stops. And with the exception of, say, the Northeast Asian tigers like, Taiwan and Korea that have made that transition, whether you are in Brazil or Nigeria or even increasingly, South Africa, the jump was never made.

The 80s, the 90s and especially the 2000 were great growth decade.

But by the time you get to the 20 tens, it kind of started to fall apart. And now in the 2020s, it’s gone and they just haven’t made the jump. Now they did kind of have the deck stacked against them. They paid for a lot of this industrialization with borrowed money from the advanced economies. And they all have had some sort of debt crisis, which definitely held them back.

But the bigger issue was China. China used predatory industrial policies to basically gobble up the industrial, capacity of all of these developing countries and moved all that industrial plant to China. The country that has suffered by far the most from that policy is, Brazil, where in the 2000s the Chinese went into Brazil, establish joint ventures with all of these companies were actually solid, maybe even world leading in their sectors.

The Chinese stole the technologies, took them back to China, build up an industrial plant that was subsidized to compete with the Brazilians on the global stage, and not only destroy the ability of the Brazilians to export to the global market. Ultimately flooded Brazil with Chinese product and destroyed those companies at home as well. Anyway, once that is done, you know, the Brazilians today would have to start over.

But they have to start over with the demographic that has changed as well, just as the Chinese and everyone else has aged. That has happened in the developing world as well, just starting from a later point. Now we’re nowhere near the point that the Chinese or the Germans, that this is not the last decade for countries like Turkey or Indonesia, Brazil, but they are aging at nearly the same rate as the Europeans almost as fast as the Chinese.

And if they can’t find a way to change that underlying economic model in the next 20 years, then they’re going to be facing exactly the same sort of demographic pressures that the Europeans and the Chinese are facing today. So it’s not all the same for everybody, but all the trends are they’re just wrapped up in a slightly different picture.

And it does mean that for the remainder of the first half of this century, we’re looking at most of the growth patterns that were established that were very, very fast at the beginning of the century, simply falling apart because there’s no demographic wherewithal to carry them forward, or the countries haven’t been able to modernize and diversify their economic structures enough to get out of the commodity rut.

And that is a pretty dark picture for a lot of countries. There just aren’t enough that have made the transition in order to carry us all along.