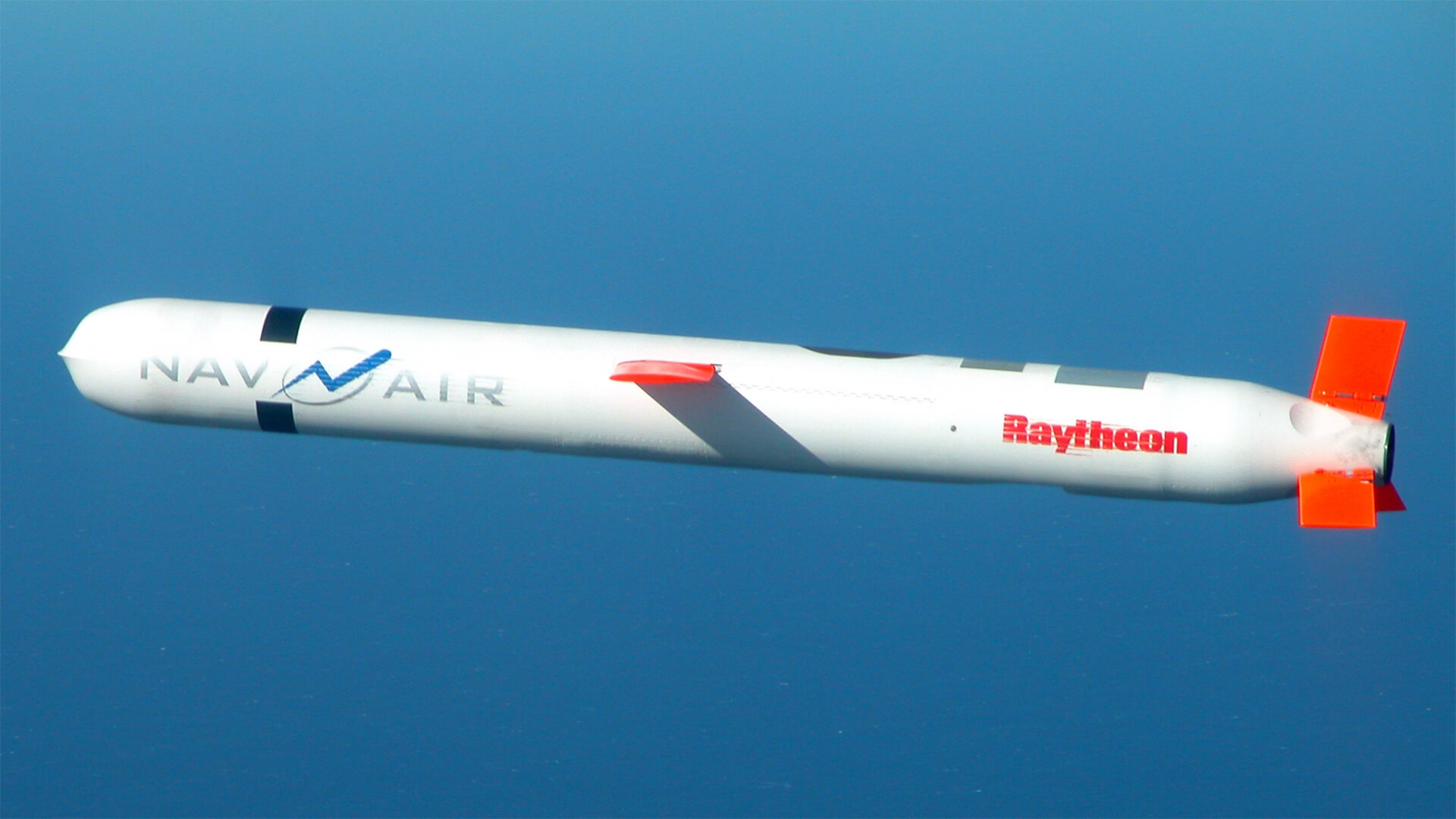

Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, the US has been trying to figure out the appropriate level of involvement. Tomahawk Missiles would be quite the game-changer for this cyclical conversation.

Ukraine’s current long-range drones are built for carrying out pinpoint strikes on smaller targets. So, a ~1,000-lb warhead with ~1,600-mile range wouldn’t just be a small step up, it would be a leap. But we’re not just talking about handing over the Tomahawks and waving good-bye, the US would have to give prototype US launch systems that would be used in directly targeting Russia.

Transcript

Hey all, Peter Zeihan here. Comedy from Colorado. Today we are taking a question from the Patreon page. Specifically, do I think that the Trump administration is going to send a Tomahawk missiles to Ukraine? And if so, what sort of damage would they cause? Let’s start with the damage. Then we’ll go to the decision. Ukrainians would love to get their hands on tomahawks.

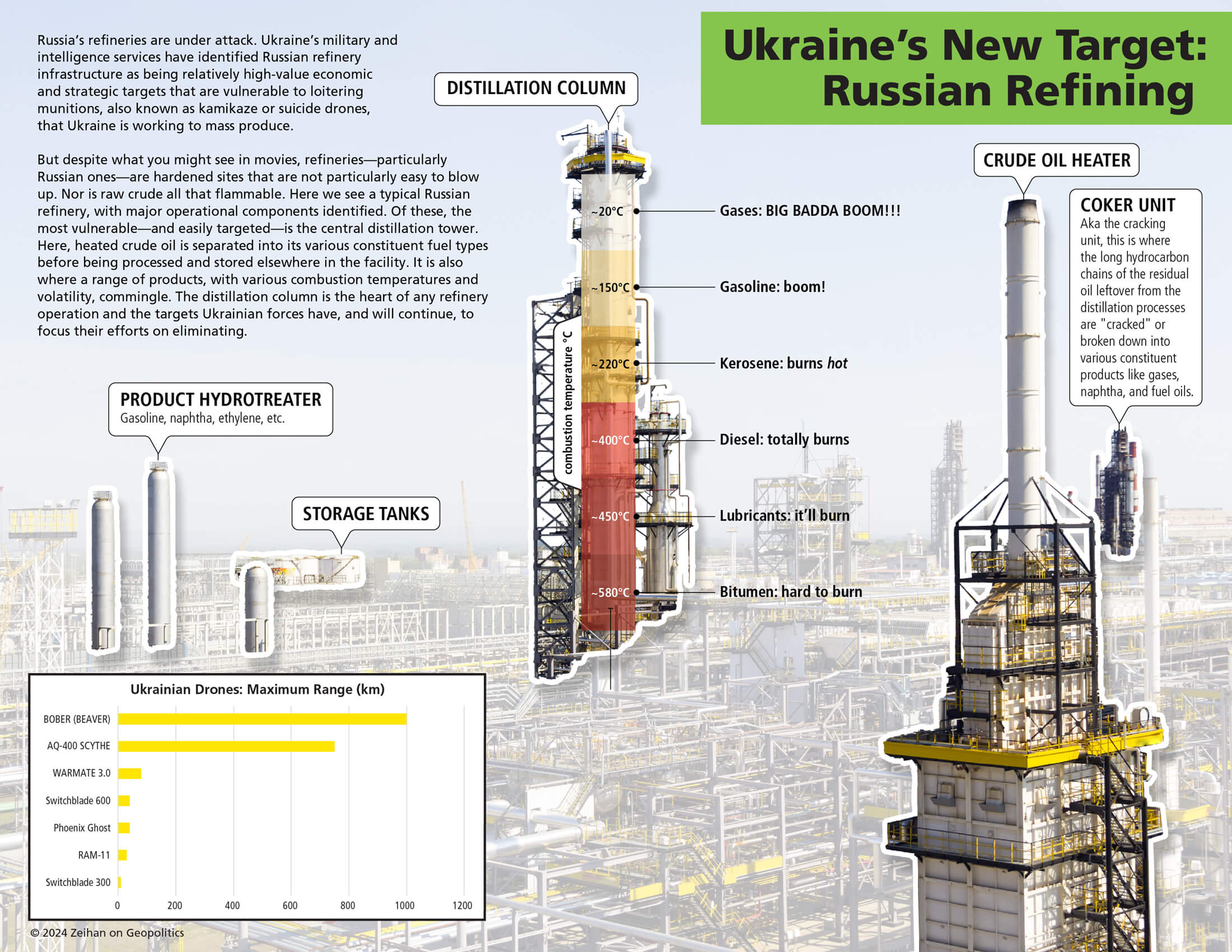

Now, the Ukrainians have, shown no shortage of creativity and ingenuity when it comes to developing their own drone program. They now have drones that can regularly go several hundred miles. And they even have rocket drones that can go almost a thousand miles, and have used these things to attack pinpoint targets. But that’s the problem.

Pinpoint targets, these sort of drones just can’t carry big warheads. So the good for targeting specific pieces of infrastructure? But they’re not good for mass damage. So if you want to say target the distillation column on a refinery grate, you want to take out the entire refinery? No, because those complexes, even in Russia, where the refineries are smaller, are like a quarter of a square mile, and you’re not going to take that out with 100 pound warhead.

So they send fleets. But even then, you’re not going to attack, a really big building. It’s just not going to do appreciable damage. The Tomahawks, however different, a Tomcat carries a 1,000 pound warhead and can carry submarine mission. So you’ve put 2 or 3 of these into, like a four acre building, and you can basically take out the whole thing.

They also have a range of about 1600 miles, which is almost double what any Ukrainian drone can do. So the idea is you would use these things, launch them from western or central Ukraine, nowhere near where the Russians could do anything to interfere with the operation. They fly low. They can’t be intercepted and they take out facilities deep, deep, deep into Russia.

The three facilities that the Ukrainians would probably use these against are all drone production facilities. There’s one near Moscow. There’s one in the yellow book, which is in Tajikistan, which is at kind of the far edge of where the Ukrainians get it with the drones right now and and the third one is further east, getting into proper Siberia. He’s up to, maybe about 1300 kilometers away. Anyway, these are where things like the Shaheed are being mass produced, where the Russians own systems are being mass produced, where Chinese parts are coming in and being assembled. And if those three facilities could be taken out, it would really change the face of the war in a very big way.

Now, that doesn’t mean it’s going to happen. And the problem isn’t so much political, because we know that Donald Trump has really no problem with political niceties. The problem is technical. The tomahawk was designed for the Navy. It’s fired from submarines and destroyers, neither of which the Ukrainians have. And even if they did, can’t exactly quickly retrofit something to take a 20ft long missile, that was designed by a different country.

So these things would have to be put on trucks. Now, the Americans are at the prototype stage of putting Tomahawks onto trucks. The idea was you hand them over to the Marines and they take them out to islands in the Pacific theater. And if a war spins up with the Chinese and you basically have these mobile launch platforms that can basically sink half the Chinese navy before the Chinese Navy even knows that war has been declared.

Great little program. Problem is, it’s not ready. It’s only a prototype stage. So if the Trump administration was to do this, they would be sending the Ukrainians prototype weapons that haven’t been through the full testing regime in, in order to attack Moscow. Hopefully it is obvious that if that decision was made that we are in a fundamentally new position, not just with this administration’s risk tolerance, but with the war overall.

So I would argue that this is not something that is going to happen. If it does happen, well, then we are in a fundamentally new chapter, and the Americans have decided to use the Russians as a testing ground. And that is a very different sort of political commitment. Now, the rhetoric out of the Trump administration has changed radically in the last six weeks.

So I am expecting a significant change. I am expecting more blam stuff from the Americans to go to the Ukrainians. But remember this weapon system in the form that it could be used does not yet exist. So if we do get there, we’re in a new world and we’re using Moscow for target practice.