WE’RE LESS THAN A WEEK AWAY FROM THE WEBINAR!

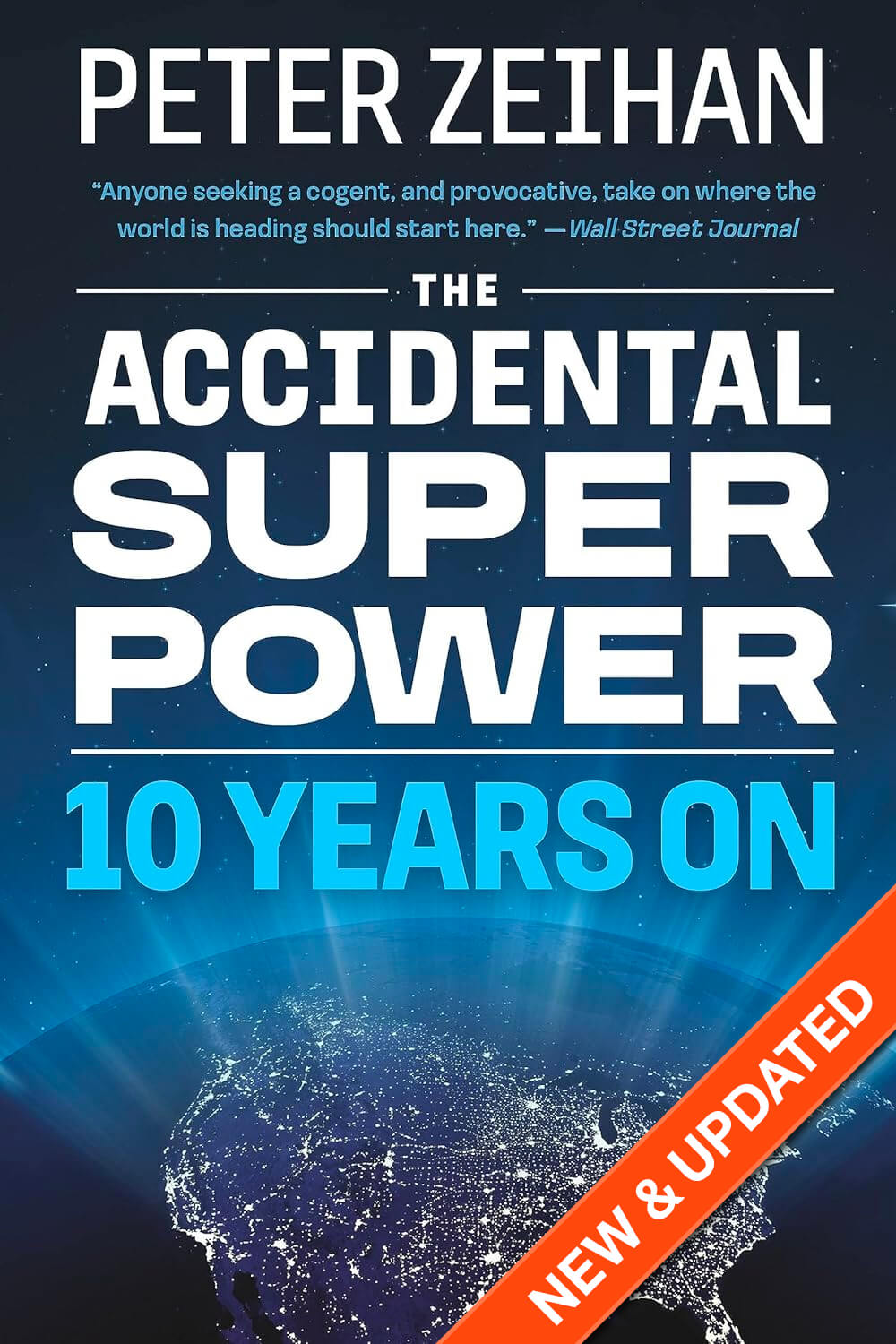

Peter Zeihan’s Risk List: What Keeps a Geopolitical Strategist Up at Night

Please join Peter Zeihan for a webinar on June 5th at 12:00 PM EST on a topic that is near and dear to the hearts of the Zeihan on Geopolitics team: geopolitical risk. This webinar will feature Peter’s reasonable-fear list, focused on issues that in his opinion have the most potential to impact market outcomes.

Well, we’ve all heard the news at this point. Trump is a FELON, after being convicted on 34 counts of financial fraud related to hiding his affair. So, can Trump spin this “publicity” in a positive light or will it bite him in the ass come November?

The case was fairly straightforward, given the clear evidence and testimonials, but we’ll have to wait until July 11 for Trump’s sentencing. I wouldn’t expect him to see any jail time; however, the potential for probation and a (likely) dragged out appeals process could have significant impacts on his campaign schedule.

The real question is how does this effect Trumps shot at the presidency? It was already going to be a long shot for Trump, so this conviction and the fallout it carries might be the kiss of death. All Biden has to do now is just keep breathing.

Here at Zeihan On Geopolitics we select a single charity to sponsor. We have two criteria:

First, we look across the world and use our skill sets to identify where the needs are most acute. Second, we look for an institution with preexisting networks for both materials gathering and aid distribution. That way we know every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence. Then we give what we can.

Today, our chosen charity is a group called Medshare, which provides emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it. Until future notice, every cent we earn from every book we sell in every format through every retailer is going to Medshare’s Ukraine fund.

And then there’s you.

Our newsletters and videologues are not only free, they will always be free. We also will never share your contact information with anyone. All we ask is that if you find one of our releases in any way useful, that you make a donation to Medshare. Over one third of Ukraine’s pre-war population has either been forced from their homes, kidnapped and shipped to Russia, or is trying to survive in occupied lands. This is our way to help who we can. Please, join us.

Transcript

Hey everyone Peter Zeihan here. I am, on my way to Milan to fly home, and you guys just couldn’t wait for me to get home and get sucked me back into politics. Okay, so when I woke up this morning about the. Donald Trump has been convicted in New York for eight of 34 counts of laundry and financial fraud.

for hiding a, a theater, attempting to hide an affair that he had with the porn star Stormy Daniels. the way it works is …., 34 felonies, felony. Because if you engage in fraud and attempt to hide a crime, it automatically elevated class and felony. so let’s do a quick Q&A. what are the state things here?

And then talk about where this leads. does this mean that Donald Trump no longer run for president? no, it does not. there’s nothing in the Constitution that says but, there are who can run for president. although, funny thing, you can’t vote. but you can still run for president. number two, what’s next?

on July 11th, we get our sentencing hearing, and it is unlikely that Trump will go to jail. This was a nonviolent crime, and he’s a first time felon. Feels weird to say that. so we’re looking at probably some form of probation. Now, probation comes with restrictions. And as we’ve seen in the trial, with all of the charges of contempt of court and, gag order, is the chances of Trump following those restrictions are going to be interesting, especially in terms of campaign setting.

number three, what about appeals? Appeals will happen. Absolutely. But it’s unlikely that we will see the appeals process completed. But before we have the presidential election, the big difference this time we’re worried about his scheduling, because when he hasn’t been convicted of anything yet, the court was believed to create in the degree of deference when it came to scheduling, now that he’s been convicted of 34 felonies.

So there’s going to be very different. So, you know, things like the debates, things like rallies, those could actually be impacted pretty severely by whatever the appeals schedule is. A Trump will, of course, have a vested interest in dragging that to other possible. But even if he didn’t do that, certainly, I could be resolved before we get to the first week of November and have the general election.

And then finally, there’s the question of whether or not this is a fair ruling or not. okay, so I’m in Italy right now, and a lot of these conversations have come up. And, you know, the Italians have some experience with politicians who dabble in corruption, politicians who dabble in ideals, and politicians who combine the two. And the general ditch here, which was really funny, is like, if you’re going to do things like this, you have to have an accountant to hide everything well and a fixer to make sure that the news doesn’t get out.

In the case of Donald Trump, those two things were the same person. So like, oh, that’s not very smart. And then second, they’re like, and you get to keep these two people as close to you as possible because they’re the ones who know where the bodies are. They’re the people who have the receipts. And the reason why this court case was sewed up so quickly, and why did the jury only need a couple of days to debate?

34 different counts, and why they came back with a unanimous verdict so quickly? Is that the fixer in the accountant and all of their documentation flipped and were testifying for the prosecution. So the only other outstanding bit of information to make this an easy case was the court star herself, who also could show for the play. Yeah, the that’s into her bank account matched with the debits from Trump’s account.

So it really was from the accounting point of view, a very open and shut case, of the hospital you can think about for this matter. It’s big impact will have on the election. And, this is just amusing from my point of view, because as soon as the verdict came in in Trump campaign headquarters, cheers erupted. I feel like we can totally fundraise off of this.

And then Biden election headquarters cheers erupted. Totally fund both of us. everyone seems to have forgotten the abuse of the 10% of the electorate, were independents, were just kind of nauseated by the whole thing. And the independents have decided every presidential election since the early 1960s. And they are not going to vote for somebody who now has 34 felonies under his belt.

So as far as I’m concerned, this verdict has decided the election or other reasons to think that Trump was already in trouble. But this is really makes it impossible for him to win.

assuming, of course, that Biden doesn’t die, I’d have never.