Well, that didn’t go the way I expected. Here’s what happened…

Here at Zeihan on Geopolitics, our chosen charity partner is MedShare. They provide emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it, so we can be sure that every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence.

For those who would like to donate directly to MedShare or to learn more about their efforts, you can click this link.

Transcript

Hey everybody. Peter Zeihan here, coming to you from a hotel room. I forgot my microphone today. I was planning on doing this from the beach, but there’s a hurricane out there anyway, so it wouldn’t have worked. So, the federal elections did not go the way I was anticipating, so I thought it was worth doing a postmortem. I’m going to remind you how I got to my conclusion, and then we can pick apart what changed.

In the last 30 years, most elections, especially at the presidential level, have been decided by a group of Americans who self-identify as independents. It’s a much smaller set than the people who self-identify, though roughly 30% of the American population self-identifies as Democrats, roughly 30% as Republicans, and the 40% in the middle call themselves independents.

But over three-quarters of that group will vote for one party or the other almost all the time, more than 90% of the time. So it’s really only a thin little sliver of 5 to 10% that has been the balance of power within the American political system for decades. They put in Obama twice, they put in Trump twice, they put in Biden, and they kicked Trump out.

When I looked at what was happening with the American political system, I thought, okay, this is the nut. This is what matters. Watch that group. Focus your predictions on that group.

When we got to the 2022 midterms, Donald Trump had spent the last two years telling independents that their votes didn’t matter and that everything should be decided at the primary level rather than the general election level. The collective response of America’s true independents was, “Hold my beer.” All but one of the races that Donald Trump put his finger on, the Democrats won. What was supposed to be a red wave in the midterms turned into, at best, a red fizzle.

My thinking was: independents are fickle. They tend to switch sides every two or three elections. They get buyer’s remorse, and it took Donald Trump really pissing them off to their core to show up twice and vote the same way twice in a row. Since he didn’t change his rhetoric, my anticipation was that the independents would do what they had done in 2020 and 2022 again in 2024.

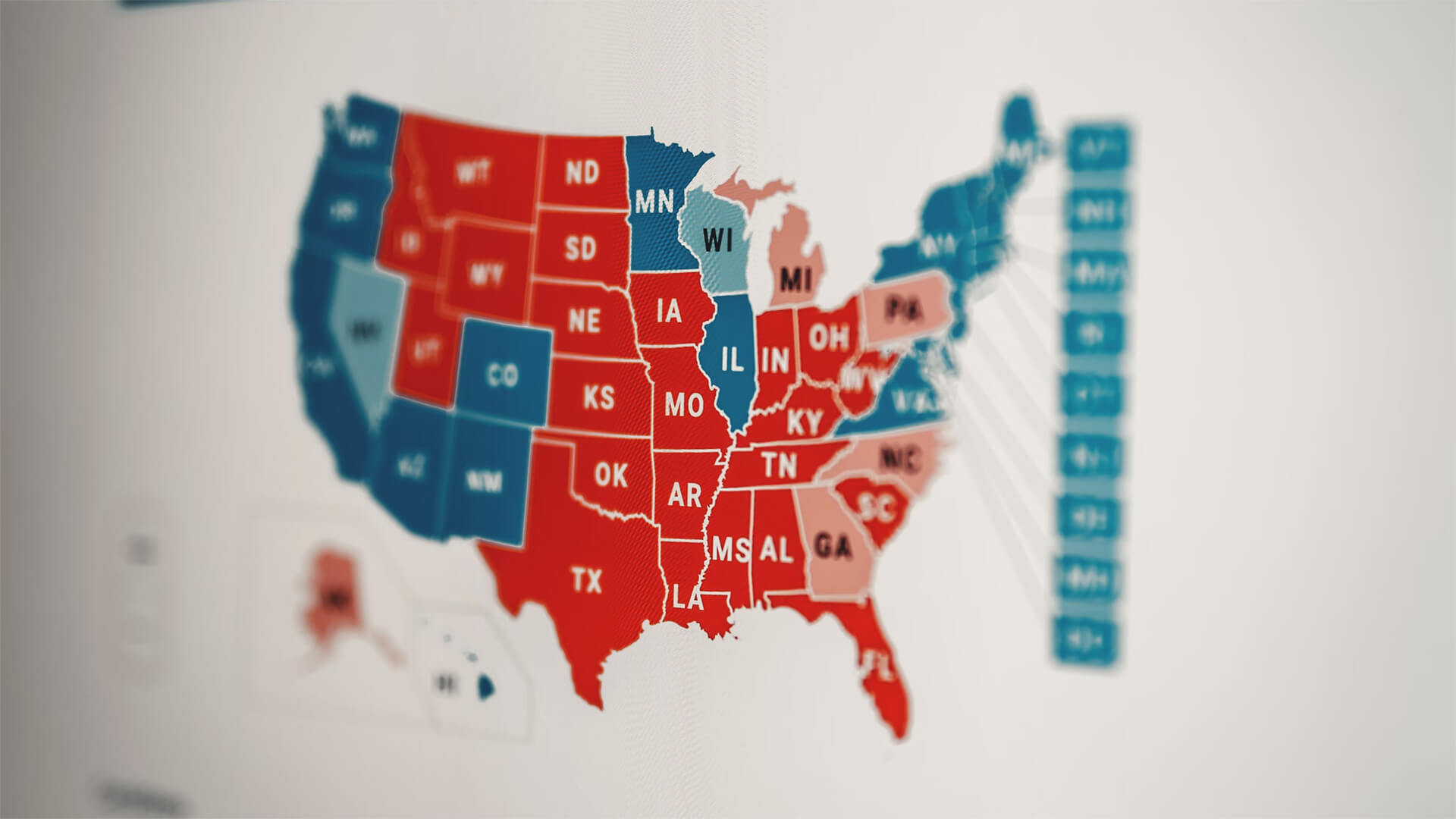

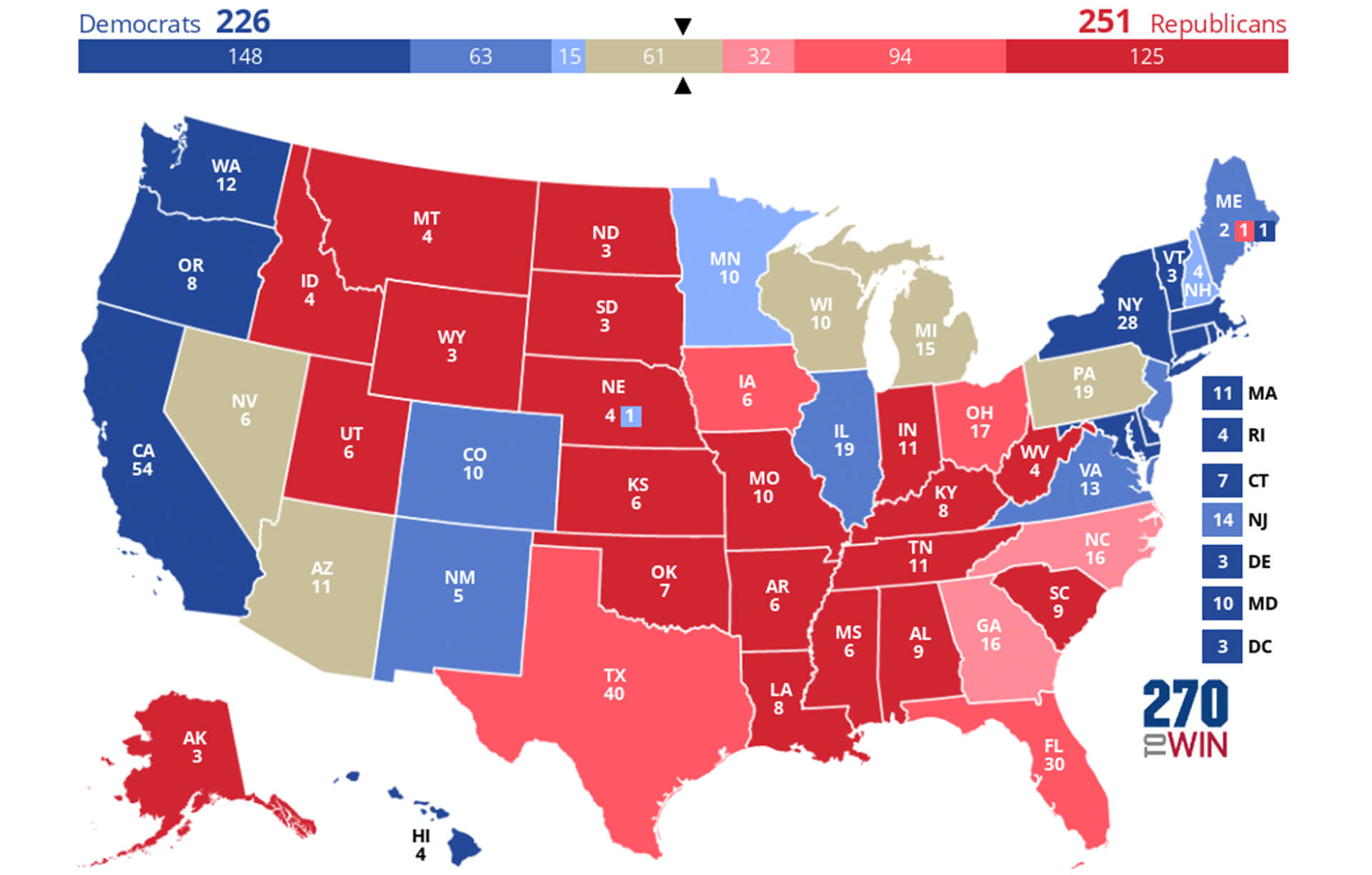

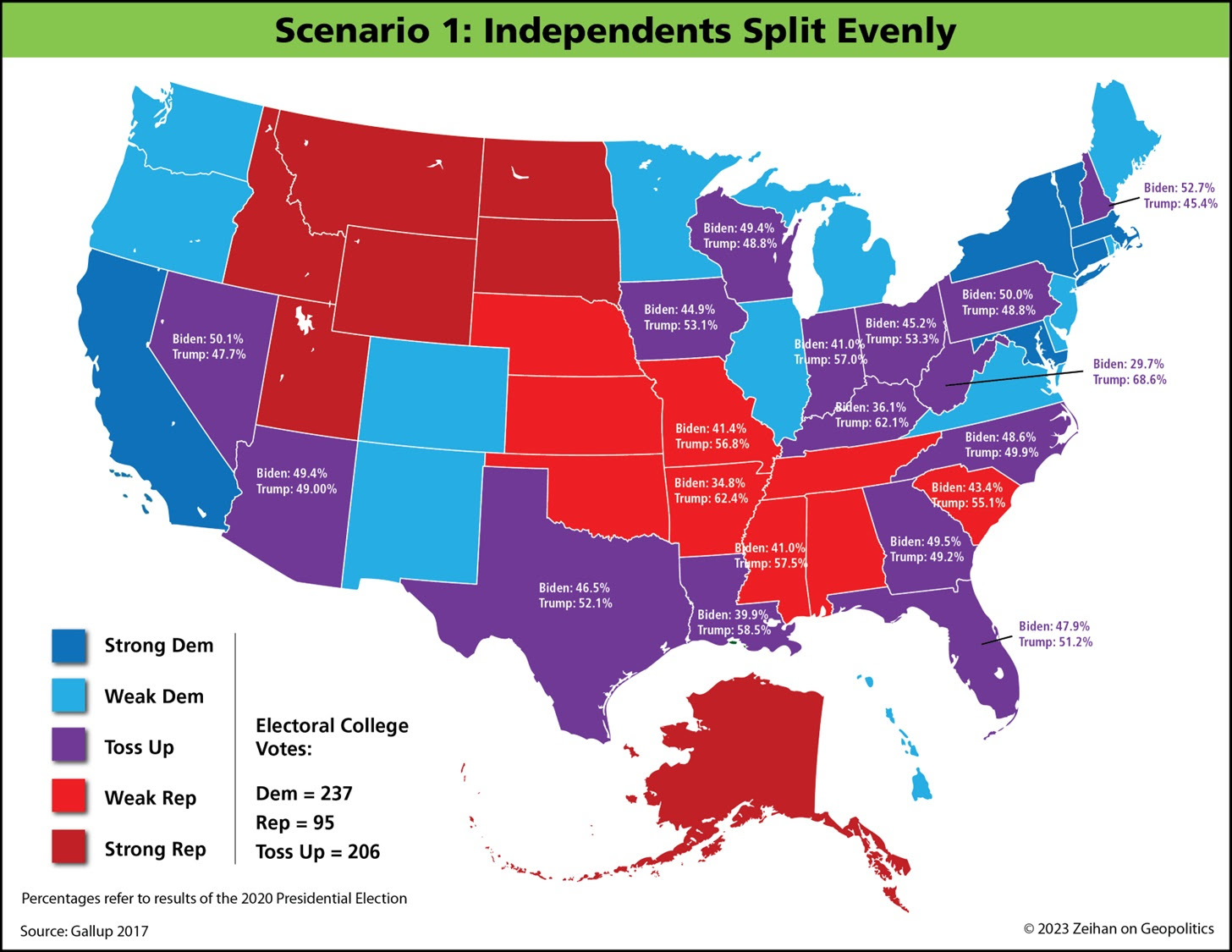

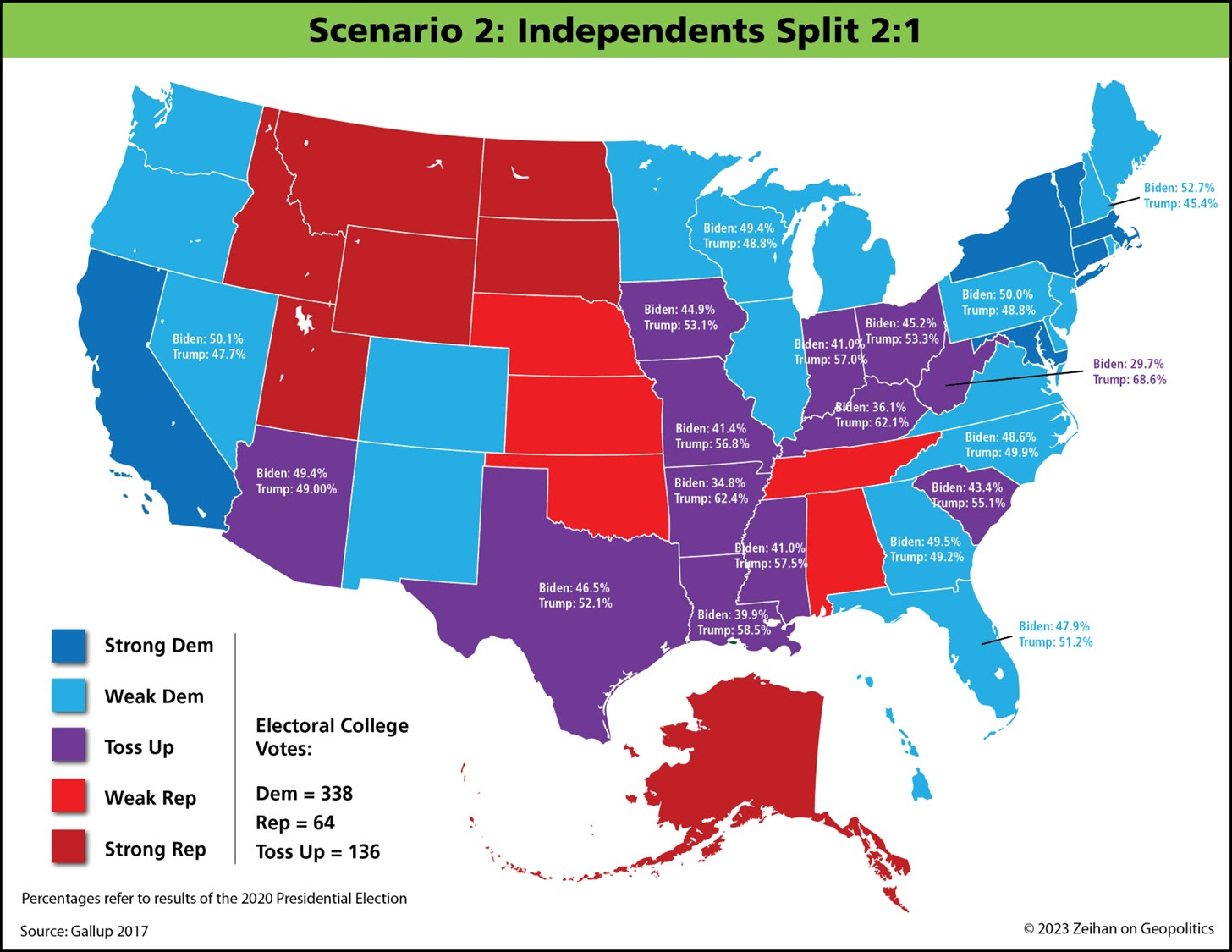

Look at these two maps.

This first one shows what happens if the independents split 50/50. You can see how, while it is an advantage to the Democrats, there are plenty of possible ways that the Republicans can pull it out of the fire. But if you get something like what happened in 2022 when the independents break very, very strongly, the second map shows a very different scenario—one that is very, very difficult for the Republicans to have any chance of success.

Some version of the second map is what I anticipated happening in 2024.

Now, we are not going to have final, comprehensive exit polling or political identification polling data until the Pew Research Group finishes their assessment. They started the day the election ended, and I doubt we’re going to get the full results of that study until probably the end of the first quarter of 2025.

But we do have expert-polled data, and we now have the final results from pretty much all of the states. Arizona and Nevada just reported, so we have some pretty good data to work with. At the onset, it appears that my prediction for the independents basically proved true. For three elections in a row, they broke very strongly against Trump.

The problem was that everyone else voted differently.

It’s like we’ve been in this lockstep for, especially the last 12 years, where you’ve got a hard-core group that’s MAGA leading a hard-core group that’s more elite-led. There hasn’t been a lot of movement in those groups. But what we saw in this federal election is a lot of bleed-over as the elite-led group just lost support over to Trump.

To give you an idea of how extreme it was:

The Democratic Alliance, as we understand it today, is based on three pillars of support. You’ve got coastal, primarily white, primarily college-educated elites; you’ve got minorities of all flavors; and then you have organized labor. What happened this time is that a lot of those pillars broke.

Women, especially unmarried women, are a big part of that alliance, but they switched to Trump by five points. Eighteen- to twenty-nine-year-olds—the youth, which almost always work for the Democrats—broke toward Trump by 6%. Black men went to Trump by 7% more than before. Nonwhite college graduates shifted by 9%. Asians shifted by 11%.

People who are in the lower income bracket, ages 30 to 49—people who you’d like to think of as “welfare queens” or whatever—broke 12% for Trump. But Latinos? Latinos shifted by 17%, with Latino men shifting 22%.

So, we saw a lot of these groups that we’ve always associated with being fairly tightly linked to the Democratic grouping break. That changes a lot.

For those of you who are on the left and are going through a lot of kicking yourself and soul-searching, I’ve seen a lot of hot takes in the last week. Just keep in mind that the voters are always right, especially when they don’t show up.

We’ve got three things going on here now that we need to keep an eye on.

Number One

We are in a period of political realignment, and party loyalties are obviously shifting. It’s very much in play. How much in play, unfortunately, is still unclear. The biggest difference we had—aside from the demographic breakdowns between 2020 and 2024—is that voter participation dropped by over 10%. Trump just doesn’t have the pull, for or against, that he once did. That makes drawing any conclusion a little fuzzy.

Number Two

With political factions in motion, a new party is being born. I can’t say right now if the current alignment that brought Trump to power for his second term is a permanent feature of MAGA—it is MAGA. This is not the Republican Alliance; it’s something new. But what I can say is that it is the end of what we think of as the Democratic Party.

Remember the Democratic pillars: minorities, organized labor, and educated white coastal elites. Well, organized labor is now, at best, a swing vote. Over half of them voted for Trump. But minorities are really where it’s at.

The fastest-growing demographic in the country, largely due to immigration, is Hispanics. People always seem to forget this: Hispanics are the group in the United States most opposed to migration in really any form. When Donald Trump made a lot of his pitch about the southern border, that really resonated with the people who, at one point, crossed. Losing those two legs—Hispanics and organized labor—out of the Democratic Alliance means that any places where those two pieces matter for local politics are, at best, up for grabs.

Without some significant soul-searching—and, more importantly, some significant alignment shifts—white, coastal, educated elites? That’s not a party. That’s a book club. It can’t win federal elections.

Number Three

We’re going to have a constitutional crisis in the next couple of years.

If you can put your personal political preferences and passions to the side for a moment and go back and look at pretty much any interview or rally speech that Donald Trump gave in the last three months, I think if you’re honest with yourself, you will see that the guy is failing.

Even if you can’t be honest with yourself, you have to admit that he is older now than Joe Biden was when Joe Biden became president four years ago. The chance of Donald Trump serving an entire term without losing his mind is vanishingly small.

Unlike Joe Biden, who has a group of peers, friends, and confidants who can tell him the truth and nudge him to make decisions—Donald Trump has no one like that. Donald Trump’s MAGA party is a cult of personality. He has purged it completely of anyone who might be able to challenge him.

What we know so far about his new cabinet is that there are going to be no members of his old cabinet who ever told him “no” or “yes, but.” That includes people like Mike Pompeo or Nikki Haley.

So, how do you get rid of a president who has lost his mind? Do you have to wait for him to die?

This is a constitutional crisis for the country because we’ve never been in this situation before. It’s also a leadership crisis for MAGA because Trump is MAGA.

How we shake out of these general trends—a little degree of voter apathy, the demise of the Democratic coalition with no clear replacement, and the coming demise of Donald Trump with no clear replacement—it’s going to be a lively time.

I’m sure I’m going to have a lot to say in the next four years. So, stay tuned.