I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but it doesn’t look like we’re all going to have personal Waymos anytime soon. There are four major hurdles.

The subsidies that have made a lot of the progress on autonomous vehicles possible are being phased out, so all that infrastructure that is needed won’t be made. Lithium is the backbone of EV’s, but most of the processing is in China; the US would need to build local capacity for this to work. Tesla, the leader of US EV innovation, hasn’t released a new model in years. And of course, the chip shortages that are coming soon will restrict growth.

So, mass adoption for electric and self-driving cars isn’t happening. There are niches where this technology will likely do well…think convoy trucking.

Transcript

Hey all, Peter Zeihan here. Coming to you from Oregon. And today we’re taking a question from the Patreon crowd, specifically what I think the future of electric and automated vehicles are specifically self piloting sort of stuff. It doesn’t look great. A couple of problems here. First of all, there are very few electric models that make sense to your average consumer without a huge amount of subsidies.

And under the Trump administration, those subsidies are basically going to zero. And if you don’t have the infrastructure in place to support charging, and if you don’t have the subsidy support, mass adoption, you’re never going to build the infrastructure that you need to support support charging. So outside of some very specific places where there just has the right concentration of infrastructure and support places like say, Oslo and Norway, this really doesn’t have much of a future in the rest of the world, most notably in the United States, where distances are large, about half the population doesn’t have a grudge to charge.

That’s problem one. Problem two is manufacturing. Right now, the vast majority, something like 80% of global lithium is processed and turned into lithium metal in China. And that is an infrastructure we’re going to lose. So if these are technologies you really want, you have to build the processing locally. And the Trump administration is actually moving in the opposite direction and removing some of the grants and the subsidies that the Biden administration established to build up this sort of infrastructure.

So that’s problem two, problem three is legacy infrastructure. It’s not just that the United States loves their cars, but in the United States, the sort of engineering that is necessary to do this thing is really held within one company. And that one company is Tesla. Tesla is arguably the most what, until recently, the most subsidized company in modern American history.

And those subsidies are also going to zero. The bigger risk here is that Elon Musk’s entire corporate empire is going to dissolve over the next couple of years. And I just don’t see Tesla, which hasn’t issued a new model in three years, being really part of the American automotive future. As for other companies, you know, Ford, Chrysler and the rest, they’ve all tried to get into EVs, running them alongside their other vehicles.

But they have proven to be not as popular because, again, that infrastructure doesn’t exist. And that means you have a huge upfront cost for people who want to do it. And so with the last data we have, which is about a year ago, over three quarters of the people who owned an electric vehicle in the United States, it wasn’t their first car, their second car, it was their third or their fourth car.

It was a showpiece. It was a talking point. It was allowing them to beat their chest and say they were environmentalists. Although I would argue, that if you look at the full cycle for producing an EV, the amount of carbon and energy it takes to build it in the first place, it’s actually not a very smart environmental choice.

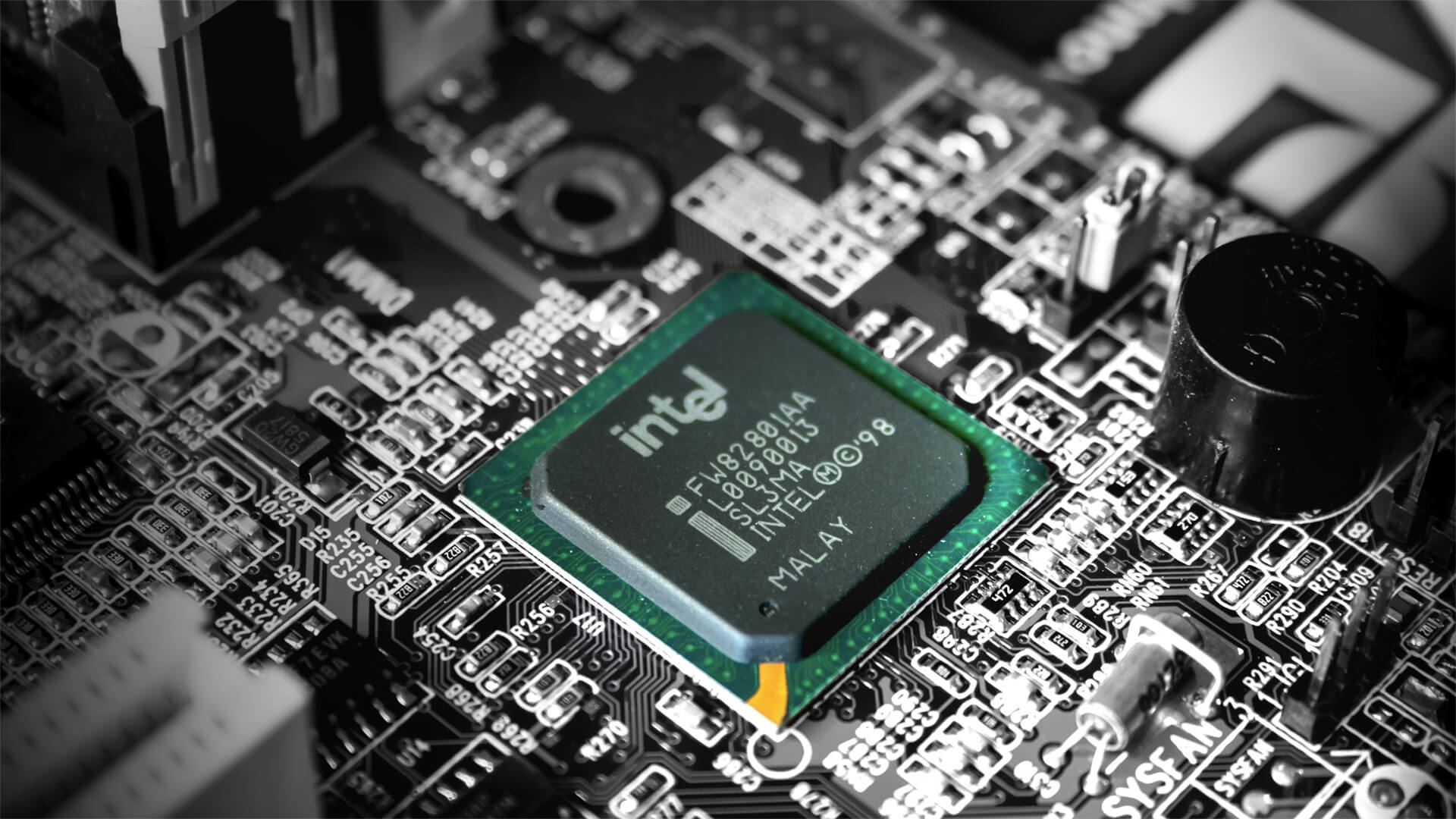

And then fourth and finally, and the one that’s going to become just crushingly important in the not too distant future, are the chips. An electric vehicle that is capable of automated piloting requires about 2000 U.S. dollars of chips. About half of those are relatively cheap and easy to obtain. The other half are the high end ones. And in the world that we’re moving into, that is the globalizing the capacity of the world to make the high end chips is going to go to probably zero, which means anything that is more advanced than, say, the iPhone 12, roughly, is something that we’re simply not going to be able to produce in sufficient volume.

If you’re going to do true auto pilot, you need a significant amount of processing power on your vehicle that is not dependent upon the weather, that is not dependent on an uplink. It has to be done locally, otherwise you’re driving yourself. So what that means is at the end of the day, your individ person vehicles are not probably going to be auto piloted, or even electric, for much longer.

That doesn’t mean the technology is going to die. It just means it needs to find a niche where it’s more appropriate. And what we’re probably going to be seeing is convoy in for trucks. Basically, your first vehicle has a driver software engineer, mechanic kind of person, maybe 2 or 3 people in it, and then a line of two, three, 4 or 5, six, seven trucks follows that first vehicle nosed tail.

The technology that is required for that does not require electric vehicles, and it requires a much lower quality of chip to make it happen. That is something we can do with today’s technology. The reason that hasn’t happened yet has to do with legal issues. Until Congress codifies where fault lies, when something goes wrong, it’s difficult for auto manufacturers to really get into the business of making automated vehicles function.

So the question is, you know, who’s at fault when there’s an accident? The driver, the person who did the last software patch, the manufacturer, the person who designed the sensor until that is sorted out, it’s going to be very difficult for EVs, as opposed to EVs to get to deeper claws into the American transport system, because if we don’t know who we’re supposed to sue when something goes wrong, then the liability gets spread out everywhere and it becomes a real mess that nobody wants to touch.

All right, that’s my $0.02.