If I were tasked with finding a location for a US-based semiconductor fabrication facility, where would I put it?

Well, just putting in a fab facility wouldn’t do much for anyone, as it ignores the enormous global supply chain that follows the fabrication stage. So, a better question would be “where would a full semiconductor ecosystem realistically go in the US?”

Places like the Texas Triangle, some coastal cities (think LA or San Fran), or western mountain cities like Denver might scratch part of the itch…but they either lack the workforce, the land, or the economics to make it work. The Midwest is the only feasible option; it’s scalable, has plenty of land and infrastructure, and has a strong blue-collar workforce that it can draw on from surrounding areas.

Transcript

Hey, all. Peter Zeihan here. Coming to you from Colorado. Today we’re taking a question from the Patreon page. Specifically, if I were to dictate where a high end semiconductor fab facility should go in the United States for maximum outcomes, where would I put it? Well, let’s start by clarifying a couple things. Number one, semiconductor fab facilities, obviously an important part of the process, but they are one part of about 100,000 supply chain steps.

From the point of imagining a semiconductor to actually getting a product, 30,000 moving pieces, over 9000 companies. Now, fabs are obviously importance where a lot of these pieces come together, but it’s not the high value part and it’s not the high employment part. It’s just a middle place where some things are done, important things, but all of the steps are important.

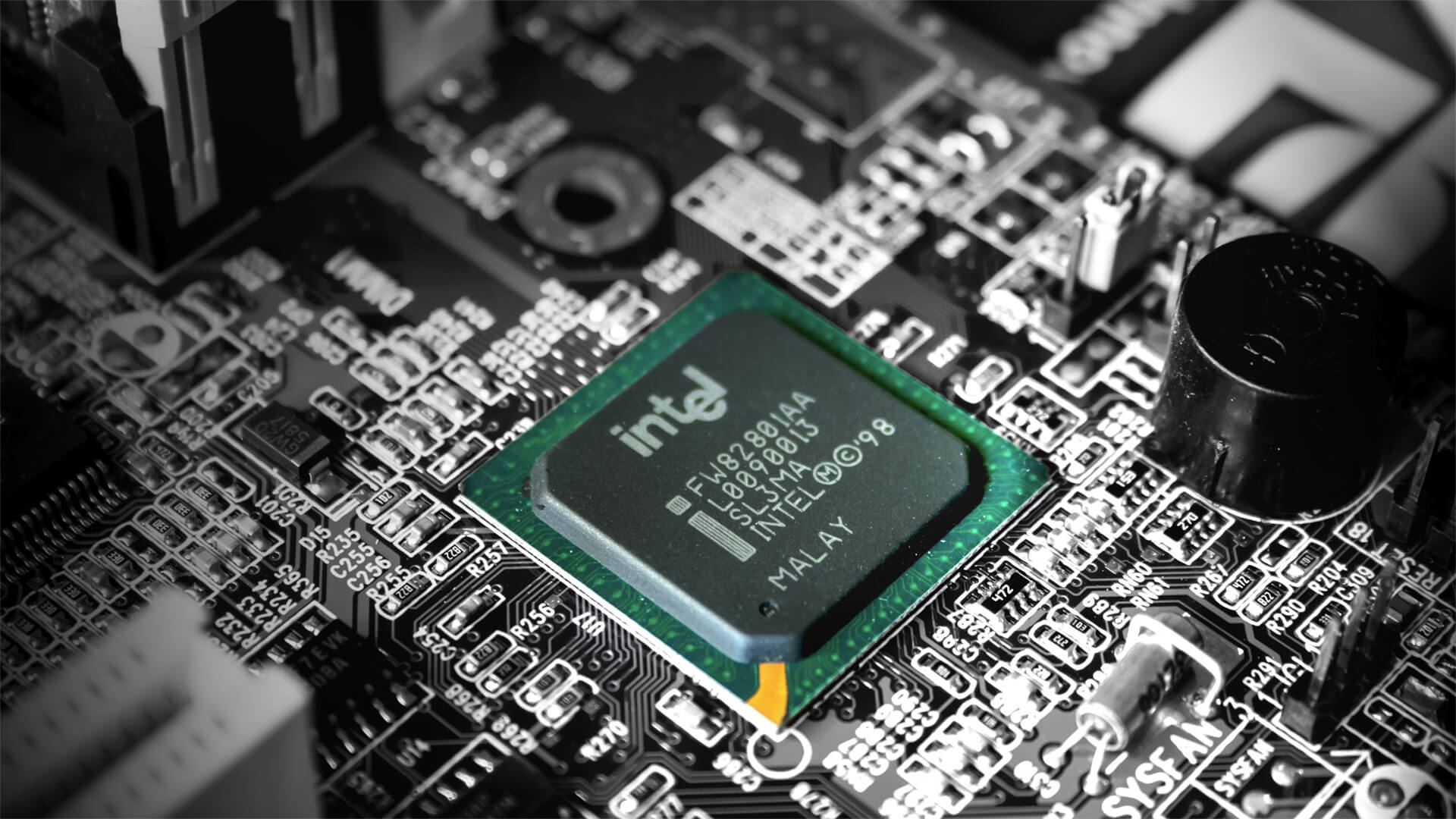

So let’s talk about process on the front end. You want to design a semiconductor. Most of that work is already done in the United States. And once you figure out how to do it, you then go to the fab company and you basically have a conversation going back and forth where you figure out how X can become a product and you eventually build, an encyclopedia that’s basically instructions on how to turn this vision into reality.

And then the supply company goes out and sources all of the materials that are necessary and makes sure that from a logistical point of view, they arrive at the right time in the right format, with the right purity. The next part of the process involves the fab. You basically take one of those purified products, silicon dioxide, melt it in a big that you put in a seed crystal, and over several weeks you draw it up and let the crystal form.

Eventually you get a crystal that weighs more than a car. You then slice it laterally into thin discs. You dope it with chemicals to make sure that the pathways you want are represented in you then run it through the EUV system. Extreme ultraviolet. That’s a giant bus size structure that, can basically etch structures down to the atomic level, and then you bake it and then you treat it again, and then you zap it again, and then you bake it in.

I make it that order, really. Is it treat, bake, etch or etch? Baked. Anyway, you do that several dozen times and eventually you get a disc that has several hundred semi-finished semiconductor circuits on it.

That’s where the fab part stops, because then that just goes somewhere else and it is cut into the individual dyes. Those dyes are stacked and tested and packaged.

Go into intermediate products that most people like, generically called chips. Then they go in to other things like wiring assemblies and motherboards, eventually built into things like system of a chip that goes into your phone, and then only then do they go into your computers and your phones and your cars and everything else. It is a very involved process, and it requires over an order of magnitude more labor and capital after the Fab than it does to actually build and operate the Fab facility.

And one of the reasons why the United States has largely gotten out of the fab business is we have seen countries, most notably Korea and Taiwan, subsidize the crap out of doing it there. So we’ve taken the step that we’re not economically good at and let somebody else pay us to do it for us. So if you bring a fab back to the United States, not only do you have to overcome those subsidies, you actually haven’t solved your core problem of all the downstream manufacturing and processing.

That’s not one company that is literally hundreds of companies. The labor force doesn’t just need to be large and well-trained. It also has to be very modular and adaptable, because what is demanded for the chips of today is not the same for the chips of six months from now or a year from now, much less three years from now.

So everything that all of those downstream companies do has to be re fabricated over and over and over and over and over. And that requires a very different sort of approach to labor. And that’s not something that United States has historically done. Great. So where can you put this sort of footprint. Because it’s not necessarily about land and water and power.

You do need this for the fact. I’m not saying that’s unimportant, but it’s really the more downstream stuff that requires a specific time of modular, adaptable workforce and large numbers. Most American cities don’t have that. When you look at places like Los Angeles or San Francisco or New York or Atlanta, there just isn’t really much of a footprint to put the fab in the first place.

And more importantly, even if you could put it there, you don’t have a dense enough labor footprint with the right skill set in these places. Even where I live here in Denver might be able to put a fab very, very easily because there’s a lot of green space, but the entire Front Range has less than 5 million people in it, and that’s probably just not enough of a labor force.

It’s necessary to do all the downstream testing, packaging, and incorporation into intermediate product TSMC has been setting up outside of Phoenix and Arizona, a place called Chandler, and has basically run into this problem over and over again. The state and the city can offer all kinds of tax benefits. The federal government can say, yes, put it there.

But the greater Phoenix area has about the same population as the Front Range. And they’re really having problems establishing all of those downstream industries that are necessary to take these fab components and actually put them into anything we might use. So what we’re seeing is a lot of it just shipped back to Taiwan, where that ecosystem already exists.

There was really only two places in the United States that you might be able to build that sort of ecosystem on anything less than a 20 year time frame. The first one is the Texas triangle, and that’s the zone of Houston, San Antonio, Austin and, Dallas. And there are a few semiconductor fab facilities there. The problem is that there’s probably no longer enough room in the labor force in Texas.

Texas has been in relative terms, the fastest growing part of the country for the last 35 years, primarily because of the shale revolution and the NAFTA accords, which made Texas the primary interface between the United States and Mexico. But to make that work, the Texans have always needed people. And while yes, it’s a no income tax state and that matters a great deal, ultimately there’s a demographic story here that is starting to turn against them.

They bring in people from the south, from Mexico, and further deeper into Latin America because of Houston. They bring people from abroad. But Donald Trump’s immigration crackdown has turned those net migrations inward into reverse. So we’re now net negative in Texas in terms of population growth when it comes to immigrants. Second, Americans used to flock to Texas for jobs, most notably Californians.

But California has rebounded since Covid, and that flow is gone. And in addition, we now have had a series of presidents that have failed to deal with issues of rising living costs. And so we’ve seen significant drops in the birth rate across the country. That makes people a little bit less mobile, a little bit less willing to move for economic reasons.

And more importantly, it just means we’re not generating enough babies sustain long term population growth. So calendar year 2025 is the first year in American history where the population has actually dropped, with the exception, of course, of the Spanish flu. And in the case of Texas, for the first time in 40 years, they’re no longer seeing the inflows of people.

So their population has for the first time started to stagnate. That tells me that if you take all of the manufacturing that already exists in Texas, there might not be enough room for a fundamentally new sector that works very differently than everything they have in more traditional manufacturing, the only option that remains is probably where this is going to happen.

And that’s the Midwest. The Midwest has a number of major cities, none of which are anywhere near as big as places like Houston, of course. But you have a lot of flat land. You have good infrastructure, road and rail link in the area together. You have a huge number of small towns that have still the highest birth rates in the country outside of the Mormon country, out in, Utah.

And because of the legacy industries in this region that reach all the way back to the Steele era in the 1800s, you have a lot more blue collar workers than white collar workers. And most of these jobs in the post fab industry are some flavor of blue collar, mid-career training.

There’s just kind of normal for these folks. So you could drop a semiconductor fab facility outside any of the major cities and be able to draw on the broader region, which has over 40 million people, fairly easily. This is one of the many reasons why Intel has chosen to put their new facility directly outside of Columbus, Ohio, to tap the broader Midwest worker community.

You could probably do something very similar outside of Saint Louis or Minneapolis or even Chicago. And in doing so, tap a lot of these secondary cities that we think of somewhat accurately as time having passed by. And that’s true whether it’s green Bay or Milwaukee or De Moine or Indianapolis or any of the others. So if you’re looking for a full transplant, if you’re preparing for a world where the Chinese are gone and this is just a sector, we need to expand by an order of magnitude, the Midwest is probably where it’s at.

But the obstacles are many. The investments will be huge. So whatever going to do front load it.