*This video was recorded during my backpacking trip through Yosemite in the end of July.

The Baltic states – Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania – are taking one step closer to the Europeans with their upcoming electrical system swap. This switch from Russian to European electrical standards marks a significant shift for these nations.

Since the Baltic states industrialized under Soviet rule, their electrical systems have long been geared to Russian technic norms. While other similar countries transferred over to the European standard, the Baltic transition was made slower due to the geography and proximity to Kaliningrad. This was amplified by demographic issues and slow growth that have plagued these countries.

The electrical switch is a critical step in integrating the Baltic states into the broader European system and it reflects the ongoing progress these countries are making.

Here at Zeihan On Geopolitics we select a single charity to sponsor. We have two criteria:

First, we look across the world and use our skill sets to identify where the needs are most acute. Second, we look for an institution with preexisting networks for both materials gathering and aid distribution. That way we know every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence. Then we give what we can.

Today, our chosen charity is a group called Medshare, which provides emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it. Until future notice, every cent we earn from every book we sell in every format through every retailer is going to Medshare’s Ukraine fund.

And then there’s you.

Our newsletters and videologues are not only free, they will always be free. We also will never share your contact information with anyone. All we ask is that if you find one of our releases in any way useful, that you make a donation to Medshare. Over one third of Ukraine’s pre-war population has either been forced from their homes, kidnapped and shipped to Russia, or is trying to survive in occupied lands. This is our way to help who we can. Please, join us.

Transcript

Hey, everybody. Peter Zeihan here, coming to you from the Hoover Wilderness. This is the northwest shoulder of Slide Mountain. I’m in the part where Yosemite merges into the Hoover, and there are so many things to look at that they haven’t even bothered naming most of them. Anyway, taking an entry from the Ask Peter forum today, specifically asking for comment about the effort in the Baltic republics.

That’s Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, the three Central European states on the Baltic Sea, who are switching their electrical system over from Russian standards to European standards.

This has been a long time coming. They’re actually already using European generation assets, but they do use a different frequency. If you remember back to the bad old days of the Cold War, everyone was convinced for a while, pre-1985 roughly, that they needed to control their own manufacturing system. So we all had our own electrical networks—the Soviets had theirs, the Americans had theirs, the Brits had theirs, mainland Europe had theirs, Australia, and New Zealand had theirs, blah blah blah. Wow. It was really annoying. Anyway, now that the Baltic states are no longer part of the Cold War and no longer part of the Soviet Union, they are finally switching over.

While the connections are already in place to draw power from the European space, this will be changing the frequency as well. So basically, everything’s going to go down one day next year, I think in March, and then it’s going to come back up and they’ll feel a little bit more European.

This is one of the many problems that the Balts and really all of the Central Europeans have had in adapting from Soviet life to European life. Most of these countries had their first taste of industrialization under Soviet rule in some way. And don’t make that think that they’re laggards because, you know, Sweden had their first taste of real industrialization in the 1940s and 50s as well. This is just when it happened for many, many, many people. So their systems were designed to work in a different world, and moving over bit by bit can be done, but it takes time and it takes resources.

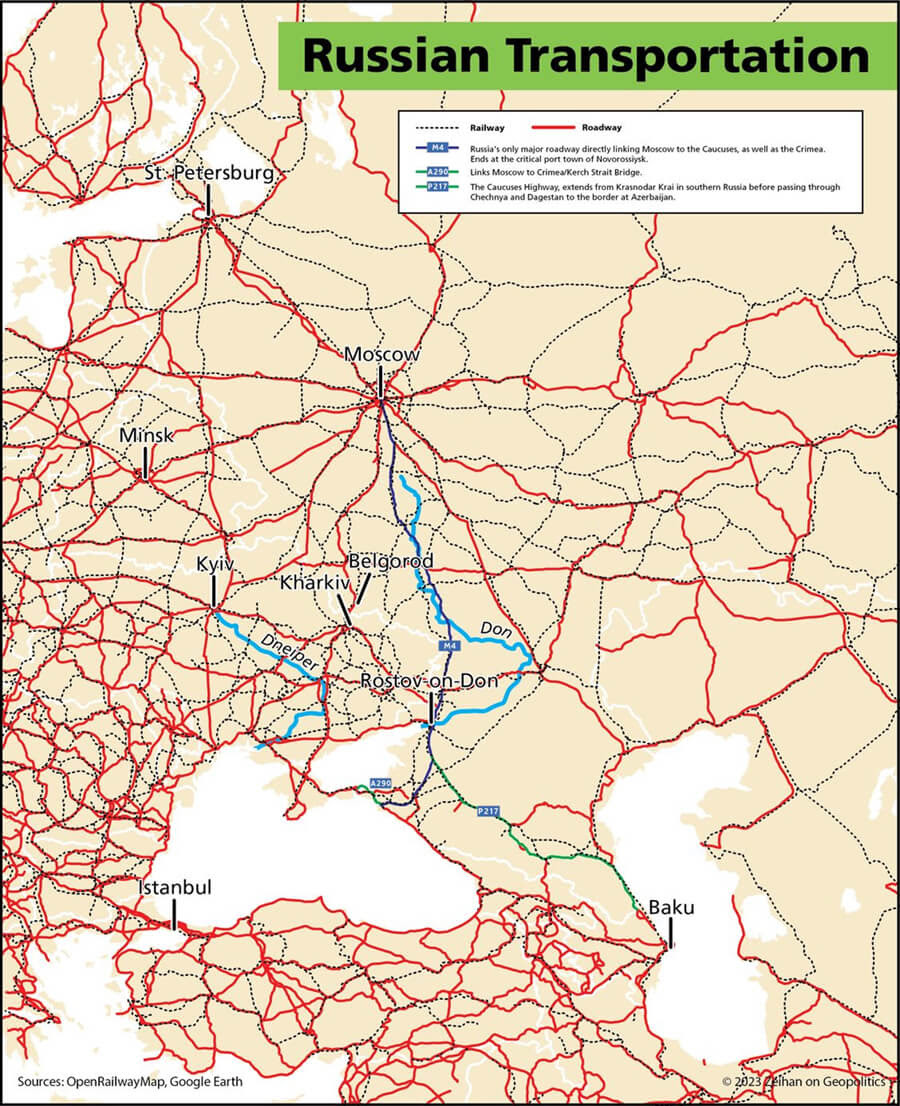

In the case of the Balts, they’re definitely the laggards in this. Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia went over very, very early because they have a lot more physical connections to Europe. For example, you can basically walk from any part of Germany to any part of Poland without a problem. The Balts are hanging off the northern end of Poland. And there’s a little problem in this little enclave called Kaliningrad, which inhibits direct connections between the greater EU and the Balts. Basically, you’ve got this little pocket of Russian territory that’s on the Baltic Sea.

Kind of reminds me of, I don’t know, Washington, DC, without the governance. You get all the dirt, all the traffic, all the corruption, and all the bad weather, but none of the power. Well, that’s kind of what it feels like to me anyway. Rooting around that has always been difficult because there’s a security issue.

There’s something called the, let’s see, I’m going to butcher this name, Suwałki Gap, which is the thin layer of territory that connects a sliver of Poland to a sliver of Lithuania. They’re building out infrastructure to make that a more viable connection, but it takes time. And remember that the Balts are called the tiny Baltic republics for a reason.

These are not large states. And when they got into the European Union, and they got into the Schengen zone, and they got into the free movement treaty, a lot of people who were in their 30s or younger left. So the total population for all three Baltic states combined is only about 8 million. I mean, geography’s a bitch. If you’ve got this kind of weak connection and then that kind of population density, there’s only so fast that you can go without a lot of outside help.

Now, the European Union, with development funds, has been paying for some of this, but ultimately the Balts have to dig deep. There’s also been talk about the Swedes and the Finns doing more, like maybe having a bridge or a tunnel from Finland to Estonia. But you should put that out of your mind right now because Finland only has like 5 or 6 million people, so it would never be viable.

Anyway, this is one of the many, many reasons why back in the day, in the 20s, I was like, if you’re going to expand NATO, great. Poland, obviously; Hungary, obviously; Romania, obviously. But the Balts? Should we really be extending the defense guarantee to countries that couldn’t be defended? But that was 20 years ago. And in that time, the Balts and the Europeans have come a long way in building connections among them.

And more importantly, in Ukraine, where we’ve seen very, very, very clearly that the Russian army is not all that, and they’re burning through their men and their equipment at a rate that they just can’t replace. So while it’s still a meaningful conversation about defense of the Balts, because they are very exposed and at the very end of a very long chain of logistics, it’s no longer silly to have that conversation.

So I see this electrical switchover as another small step in a multi-decade process to make the Balts part of the free world. So far, so good.