Hey everybody. Peter Zeihan here. Coming to you from Colorado. It is the 3rd of December.

Today we’re talking about something that happened in the former Soviet Union over the Thanksgiving holiday in the United States. And that is, we seem to have the beginnings of an uprising in the former Soviet state of Georgia.

Now, for those of you who follow this, Georgia, not Peach and Atlanta, Georgia, the one that’s in the Caucasus, uprisings here seem to be happening often. And the reason is that the Russians are getting a little nervous about political evolutions there.

The Russians are far more sensitive of what’s going on in Georgia than they are in any, of the other former Soviet provinces, with the notable exception of Ukraine, which is, you know, where there’s a war. It has to do with the geography. It has to do with the ethnography, and it has to do with how the Russians manage their political system.

So the specific trigger for the most recent protests, we’re talking about here, about a country with under 6 million people and over 100,000 people showed up to protest over the weekend. Is that the current government, which just cheated its way into a new term, had elections recently that were neither free Norfair, they announced that they are going to drop their bid to join the European Union specifically.

And the Georgians have often thought of the EU as their only way from getting out from under the, Russian thumb. I’m not suggesting that that would work, but that’s certainly the plan. The idea is that NATO is a bridge too far. NATO is too far away.

But if you go with, say, a European economic grouping, maybe that will work anyway, whether or not that would work or not. But outside the point, the current Georgian government is under Russia’s thumb. Russia is a multi-ethnic empire. The Soviet Union was as well. It has to do with geography. The core Russian territories around Moscow, are largely indefensible.

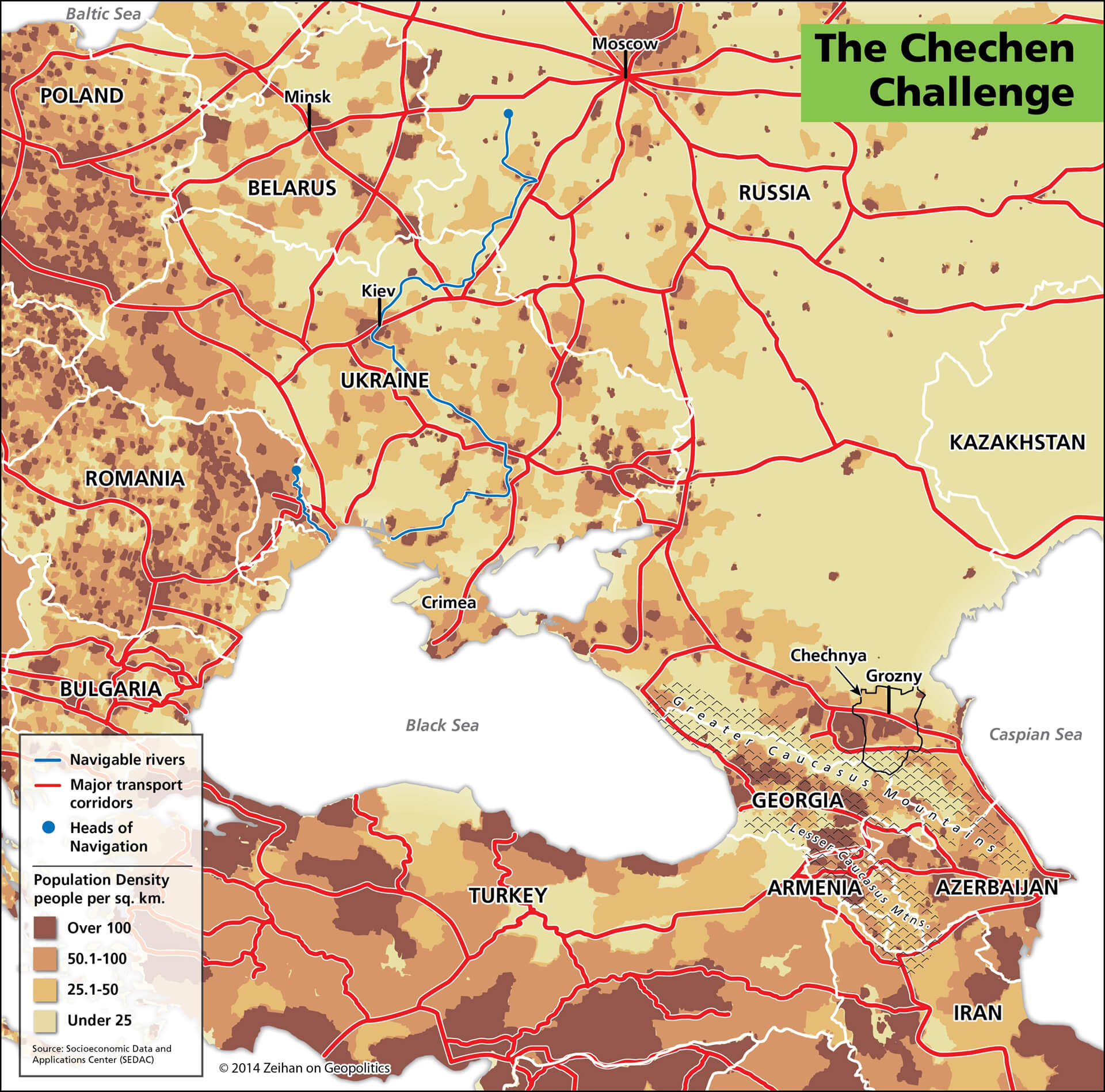

Aside from a few fours and a couple chunks of swamp, there’s just nothing to hunker behind. And so, going back to the time of the early czars, the strategy has always been the same. You expand, you expand, you expand, you conquer everybody. You you neighbor, you turn them into cannon fodder, and then you conquer the next line out and you keep going and you keep going until you eventually you get to a geographic barrier that you can hunker behind the Carpathian Mountains, the Baltic Sea, the car come desert the tension mountains, whatever they happen to be.

And in the cases of the, the Georgians, it’s the Caucasus Mountains, both the greater caucuses, which are immediately to Georgia’s north, and the lesser caucuses, which are part of Anatolia and Persia to the south. So the Georgians are on the frontier from the Russian point of view. And when the Russians conquer a people like they functionally have in Georgia now, they assign a local, who is a little bit creative in their loyalties.

Most people would use the word traitor, to rule them indirectly so that the Russians can occupy themselves with other things, like conquering other people who are causing problems, like in this case, Ukraine. In the case of Georgia, that guy’s name is, let’s see if this is right. But Xena Ivanishvili even. Yeah.

You have to have five syllables to be a good Georgian name.

Anyway, he is an oligarch who made his money in the post-Soviet collapse. He is a former prime minister of Georgia, and now he is basically Russia’s front man. He sees himself in his position as linked to Russian power, which is how a good stooge works. And so he will do what the Russians want in order to protect himself.

He believes that there’s a certain amount of power to be had in this country. And if he shares with anyone, that won’t work. And if the Europeans come in, they will have different ideas on regulation and democracy and everything else. And that would see a degradation of his personal position. So he is willing to fight to the last Georgian to maintain control, and in the end will have to be removed by force if Georgia is going to find a new way forward, because he will make sure that electionscan have the refused or fair, because that would not serve his interests.

And the Russians, of course, are willing to supply intelligence and cash and disinformation to make that happen.

Now, that’s kind of piece one, piece two. Why do the Russians care so much about Georgia? I mean, it’s not that powerful of a place. The issue again is geography.

Not all Russian territories equally crappy. Some is less crappy than others.

And if you go from the Russian wheat belt going west into Ukraine, you get some of the best possible land. Ukraine, by the way, is on the footsteps of, those two most important of those access points to the Russian space and Poland and Romania. And so the Russians really want to anchor in the Danube basin, the Polish gap, and ultimately the Carpathians.

But no less important is the southern anchor, because if you follow the rainfall in Russia, it basically makes a crescent from Moscow west into Ukraine and Belarus, and then arcing south along the Black Sea into the caucuses, into Georgia, and to the north of the Greater Caucasus Mountains. You’ve got a smattering of peoples that hug the valleys, making them very difficult to dislodge.

And this is where, for example, the Chechens are from. In the case of the southern side of the Carpathians, the land is much more open. And you’ve got this interesting little pocket with the Greater Caucasus to the north, the Lesser Caucasus to the south, the Black Sea to the west, and the Caspian Sea to the east. And you have three small states Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia in there.

But Georgia controls most of the good land where you actually can have agriculture. Azerbaijan, of course, is an oil state, and Armenia is a mountain exclave. Now, when Armenia switched sides from being pro-Russian to exploring relations with the West over the course of the last couple of years, the Russians were of course upset. But the at the end of the day just kind of let it happen.

And not just because they didn’t have the power to resist because they were locked down in Ukraine. Armenia is just not as important. It’s down in the southern Caucasus is the Lesser Caucasus, if you will, and it’s a mountainous state. So it’s really just one city, Yerevan, and then a chunk of territory. And then the Russians were never going to be able to project power down there if they were busy with more important things, like they are with Kiev.

Georgia’s different. Georgia can support a larger population. Georgia has infrastructure. Georgia has agriculture. But most importantly, Georgia is opposite. The greater Caucasus from all those little micro states that the Russians have conquered, like the Chechens. So if Georgia were able to go its own way, not only would the Russians lose their primary foothold for their southern boundary, which is just as important to them as Ukraine when it comes to the West, they would also lose the ability to keep all of their little micro states, like the Chechens under lockdown, a Georgia that goes its own way in order to look out for its own interests, is going to have a vested interest in causing problems for the Russians north of the Greater Caucasus Mountains, so that the Russians never have a free hand to come south of the greater Caucasus Mountains. And so they’ve invested a lot of, hope and money and not a small number of political assassinations in the person of Ivanishvili, because they see him as the best guarantee for their position.

And he, of course, sees the Russians as the best guarantee for his position. So next steps. The United States isn’t interested. Even in a day where the United States is really raring to go and expand NATO and have an internationalist footprint. Georgia is always kind of a bridge too far. And as the Russians have shown over and over and over again in the last 30 years, them invading Georgia is not hard.

They sponsored two secessionist groups in there, one in place called Abkhazia, one in the place called South Ossetia, and in both cases they have appointed their own traitorous frontmen to run the place. They’ve got another frontman on the other side of the border in Chechnya. That’s, Kadyrov. He’s a psychopath. And so having the place kind of broken up like this serves the Russian interests, so long as there’s not a major power involved.

The problem is, if you take the long view of history here. The Turks. Impressive industry, second largest army in NATO, demographically robust, clearly an up and coming country. Iran, despite the fact that is on Russia’s side at the moment, would really rather be the premier power in places like Azerbaijan and Armenia. And so with the Russians were to get knocked back a bit.

All of a sudden the Persians get involved in a very interesting way. And while the Russians primarily are concerned about invasions from the West and Germany, they have been invaded from the south multiple times by the Turks and the Persians, both. So if this barrier fractures, things get really interesting. But it’s not going to be the United States that steps in to try to stir the pot or get the Georgians under the Western cloak or whatever it happens to be.

The Americans just have bigger fish to fry in other places right now, and probably will for the remainder of the decade. So the question is whether the Europeans are going to rise. Now, if you had asked me this five years ago, so this is a really interesting ideological and hypothetical discussion because the Europeans just really haven’t been able to belly up to the bar when it comes to great powers.

They don’t have the fiscal capacity, they don’t how to raise an army. They don’t have an army. They have a lot of individual states that think of their military as something that they protect. And, everyone is mostly interested in economic issues rather than strategic issues. They just kind of subcontract that out to the United States. That’s changing.

The first big fiscal program that the Europeans did to raise a joint debt mechanism wasn’t used to do bailouts, wasn’t used to overhaul their economies for a more technocratic age. No, it was used to buy ammo to fight the Russians in Ukraine. We’re seeing more movement on things like military spending with everyone, even the laggard Germans now saying that 2% of GDP, which is kind of a NATO flaw, what they recommend is probably not enough.

And we need to go up to three and maybe even 4% in a world where the Russians are on the warpath. And if you are European and you’re starting to admit that the European entity that is the EU or its individual states need to take more actions to protect themselves than causing problems, critical problems for the Russians, nowhere near Ukraine is a very low cost way to get a lot of benefit.

So right now the Europeans are saying all the things they normally say about free market economics, socialism and democracy and how they’re outraged. What is going on in Georgia. But it doesn’t take a big jump for the Europeans to do something that’s a little bit more traditional in terms of state power. They can support the Georgian protesters with money.

They can step in with intelligence. They can provide a little quiet assassination program if they want to get really back into old school. But the bottom line is this is a country, especially in league with the Turks, that is ripe for intervention. And any dollar or euro that is spent orienting the Georgians away from Russia is one that is going to spawn dozens of positive outcomes for the Europeans.

And even if it all fails completely, it’s on the other side of the Black Sea.

This is a very low risk, high reward series of operations that I would guess we’re going to see the European start in under a year. And if you happen to be the new Trump administration, they’re going to look at the Europeans actually getting involved.

And probably get a little thoughtful.

It’s one thing if you’re an American and you tell the Europeans you want them to spend more on defense, if you want them to take care of themselves a little bit more, it’s a very different thing when the Europeans actually start doing it and developing independent capacity based on independent decision making. One of these looks great on paper.

The other one, in the long term, gets a little complicated.