The strategies implemented by Russia and Ukraine are shifting once again.

Russia has shifted away from targeting Ukraine’s power grid and is now striking rail infrastructure instead. These mobile targets are harder to defend, and the fallout is much worse for Ukraine’s energy and logistics networks. The Russians are also closing in on Pokrovsk; this city has been a key transport hub for Ukraine, and losing it will be a major setback.

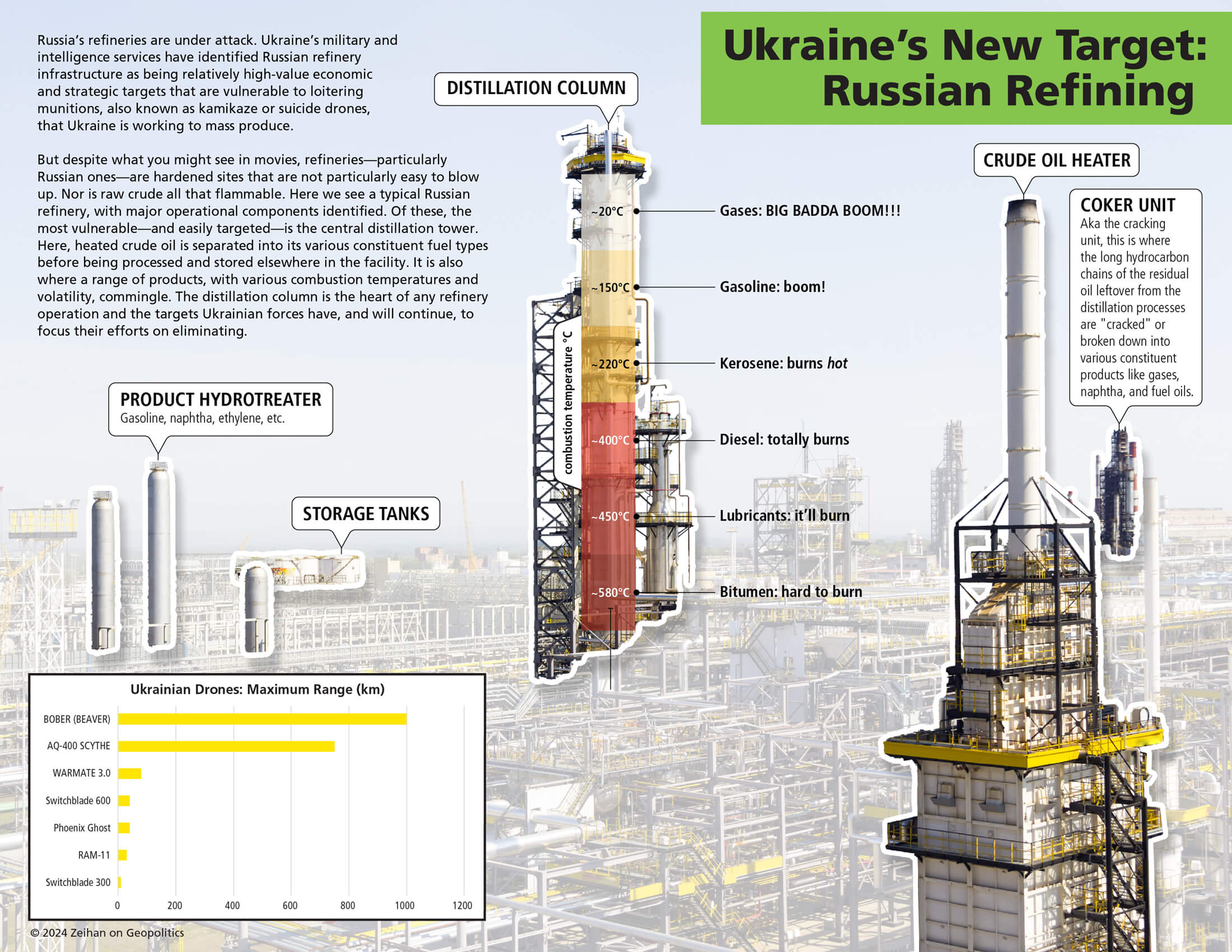

The Ukrainians are strategizing as well. Strikes are penetrating deeper into Russian territory, hitting oil infrastructure and ports. The shadow fleet tankers are included in the target list, which could open a new can of worms for the Russians and countries backing their oil trade.

These shifts have the potential to reshape not only the war in Ukraine but also global energy markets.

Transcript

Hey everybody, Peter Zeihan here. Coming to you from Colorado, today we’re taking a look at some of the new things that are happening on the Ukraine front. Three big. Number one. The Russians have changed their strategy when it comes to bombing civilian targets across Ukraine. For the last three years, they’ve been going after power plants, capacitors, transformers, that sort of thing.

Natural gas transport infrastructure, substations, all all that. What they’ve discovered is that when you’re willing to do things that are not OSHA approved, there’s only so much you can do. So yes, they can knock off the power over and over and over and over again. But the Ukrainians get a little cheap equipment. It’s been imported.

They, tie some wires together, and the power comes back on. So I don’t mean to suggest for a second that the Russians have. It inflicted a great deal of pain on the Ukrainian population, but it hasn’t had nearly the impact. I thought that it was going to have. And while, the Ukrainians have power that’s off every day, it hasn’t been able to shut the country down in the way that the Russians thought they were going to be able to.

Also, whenever you go after a power plant, it’s a known location. And while that means it can’t dodge, it also means you can in place, anti-missile and anti-drone defenses and the Ukrainians have gotten incrementally better at that. Bit by bit by bit over the last four years as well. So they’re changing strategy. The Russians are now going after the rail network and specifically the rolling stock, because you can’t have a fixed offense on a train that’s moving.

So the Russians basically figure out what the train schedules are and then send a fleet of drones and specifically go after, the engines. These are a lot harder to replace. They’re a lot more expensive. And a lot of Ukraine’s power grid now, because of damage to the natural gas transport system, has been coming from coal, the coal shipped by rail.

And so it’s having actually probably a bigger impact in a shorter time period of time, than anything that the Russians have done in the last 3 or 4 years. So having a much bigger impacts, much harder to defend against. Once you have enough drones that you can expend them on moving targets, that’s one. Number two, we seem to be nearing the end for the city of Procrustes.

Procrustes is a rail and road hub in southeastern Ukraine that the Russians have had under assault for over a year, and now they’re actually Russian forces in the city. They’re nowhere near to have clearing it and securing it, but it is no longer able to be used by the Ukrainians for transport at all. So they’re having to fall back through eight major transport arteries that combined and Procrustes, where the Russians have been after it for so long because as long as the crossing was in Ukrainian hands, the Ukrainians have been able to shuttle troops to wherever the hotspots happen to be.

You move across, even if it’s just destroyed, it doesn’t become a Russian rail hub. The Ukrainians have to fall back quite a bit and then deal with much longer routes, in order to get at things wherever they need to go. The Russians have surged more and more troops into the area, and they are on the offensive pretty much across the entire front.

They’re only making incremental gains. Like I said, they’ve been after Procrustes for over a year. But this is going to slow the Ukrainians reaction time significantly. Whether that will spell more advances for the Russians in the future remains to be seen of course, because the rules of this war change every six months. Which brings us to the third point.

The Ukrainians are targeting differently as well. They’ve been using their rocket drones and the longer range drones to go deeper and deeper into Russian territory, going after more and more sensitive energy infrastructure. And we’re now in a situation where roughly 60% of the Russian transport system for oil that matters is under the gun in some way.

The Russians, are taking hits not just in the refineries anymore, but also their ports. And on the first and 2nd of November, overnight, we had a number of Ukrainian drone strike out at a place called Tusa, which is one of the two major ports on the Black Sea. To ops is important because it serves as an outlet not just for Russian, but Kazakh crude.

And the Ukrainians didn’t simply hit the pipe control system, didn’t simply hit the loading burst. They also hit at least two, perhaps as many as four of the tankers that were there. Now, we don’t have damage reports because the Russians don’t talk. And the tankers that carry Black Sea crude at this point are pretty much all shadow vessels.

So they’re not registered with normal, law enforcement internationally. So they’re not talking either. But a couple things to keep in mind. Number one, to observe one of the four largest offloading facilities in the Russian system, even partially offline. That’s kind of a big economic hit. And it’s a lot closer than some of the targets in, say bus Korea Center.

Tatar said that the Ukrainians have already proven that they can hit. So they actually have the possibility of taking this one off line if they hit it hard enough and repeatedly enough. And the Ukrainians are showing a penchant for hitting the same target over and over and over until it’s just not in the equation anymore. This would be the first major port that the Russians would have lost to, and more importantly, is the shadow fleet vessels.

Now, part of what makes them a shadow fleet is that they are under insured or not insured at all. And in that sort of scenario, the financial risk is not borne by the international community. So if you dial back to the beginning of this war, one of the things I was really concerned about was that if a single ship went down, because it was targeted by a sovereign state like Ukraine, that we would see an unraveling of global maritime law.

The way it works is companies purchase insurance for their vessels. And if something happens to that vessel, the payout is massive. Well, part of the way the sanctions work, especially as designed by the Europeans, is that they’re no longer providing maritime insurance for the vessels that dock at Russian ports. So they have to be off the ledger. They get insurance from, say, the Russian government, the Chinese government, the Indian government, instead of normal things like, say, Lloyd’s or Swiss wheat or whatever else.

And that means that the financial risk is not assumed by the international community, but instead by these specific governments. Now, we have not had a shadow tanker sunk yet. We’ve had some confiscated. That was exciting. That happened in the Baltic Sea a few weeks ago. But we not actually had one sunk. But now we have the Ukrainians deliberately targeting multiple shadow tankers.

And sooner or later, one of them is going to go down. And when that happens, it’s going to be really interesting to see how the payout happens, because if, the Russians or the Indians or the Chinese don’t pay up and all this insurance is null and void, and then the shadow tankers are basically a free for all.

If you happen to be anyone else who doesn’t like the Russians and will probably see mass confiscations if the Ukrainians, the Indians or the Russians do payout, then the Ukrainians have every interest in hitting as many tankers as possible, because as large as a financial loss to the supporters of the Russian system, as possible. So one way or another, we have just kind of passed an interesting Rubicon, and we’re going to know in the next month or two how this is going to play out, because for the Ukrainians, there’s absolutely no downside to hitting the tanker.

There may have been a year or two ago because back then the concern of the white House was that high oil prices were going to impact the Democrats chances of elections. I thought that was really bad math. From an economic point of view, you draw your own conclusions politically. But now two things have changed. Number one, Trump really doesn’t care about economic damage with any of his policies.

So why would this one be any different? Second, and arguably a lot more importantly, we’re now in a massive oversupply situation for crude on a global basis. We’re probably somewhere in the realms of 2 to 4 million barrels a day. Too much crude. Which means that if it wasn’t for all the risk premiums out there, political, geopolitical, military or otherwise, we’d probably already have an oil price crash, which means that the world can get by with substantially less Russian crude than it thinks that it needs. It’s all adding up for a lot more direct action from the Ukrainians on all Russian energy targets. And I think the shadow fleet is where we need to watch the most closely.