Coming to you from Milford Sound in New Zealand.

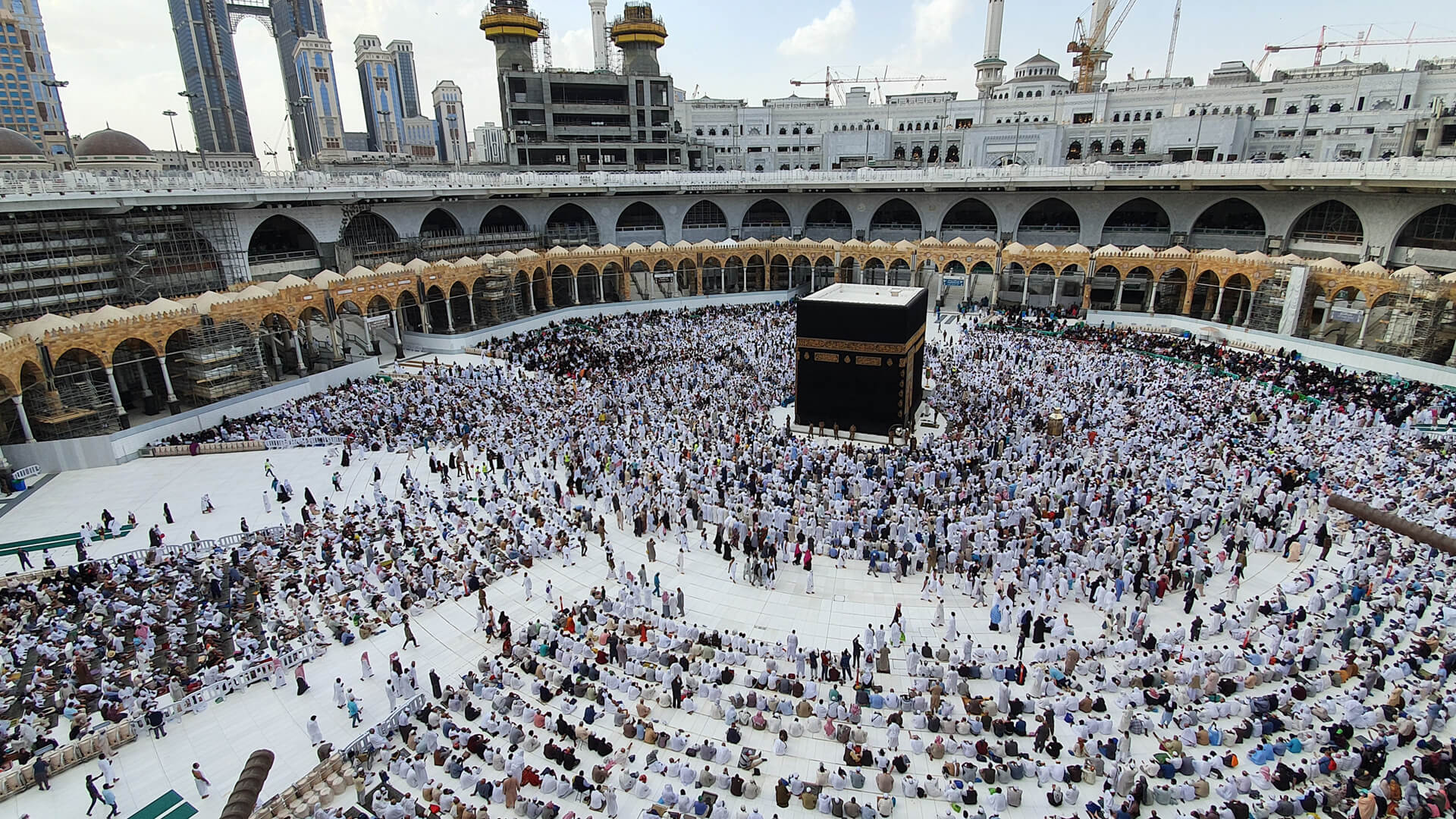

The demographic situation in the Middle East can be explained by three factors: water, oil, and food. Water prevented the population from expanding. Oil generated the capital needed to industrialize and help the population grow. Food security will ruin all of this.

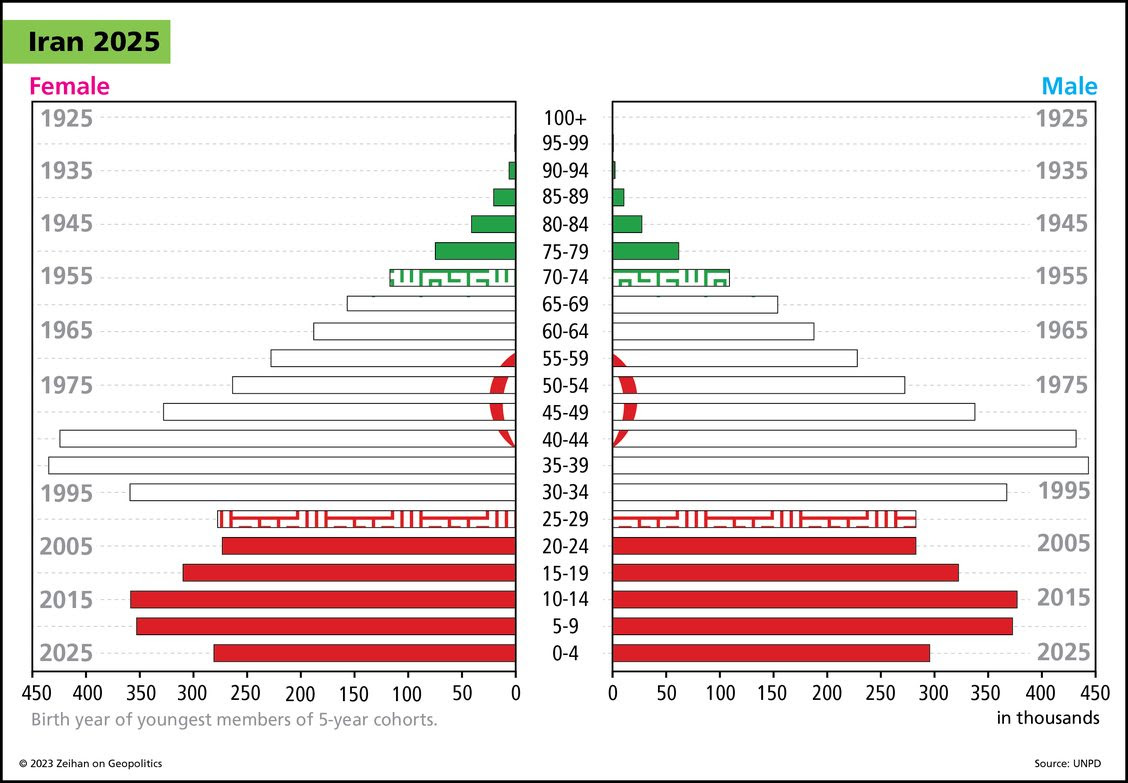

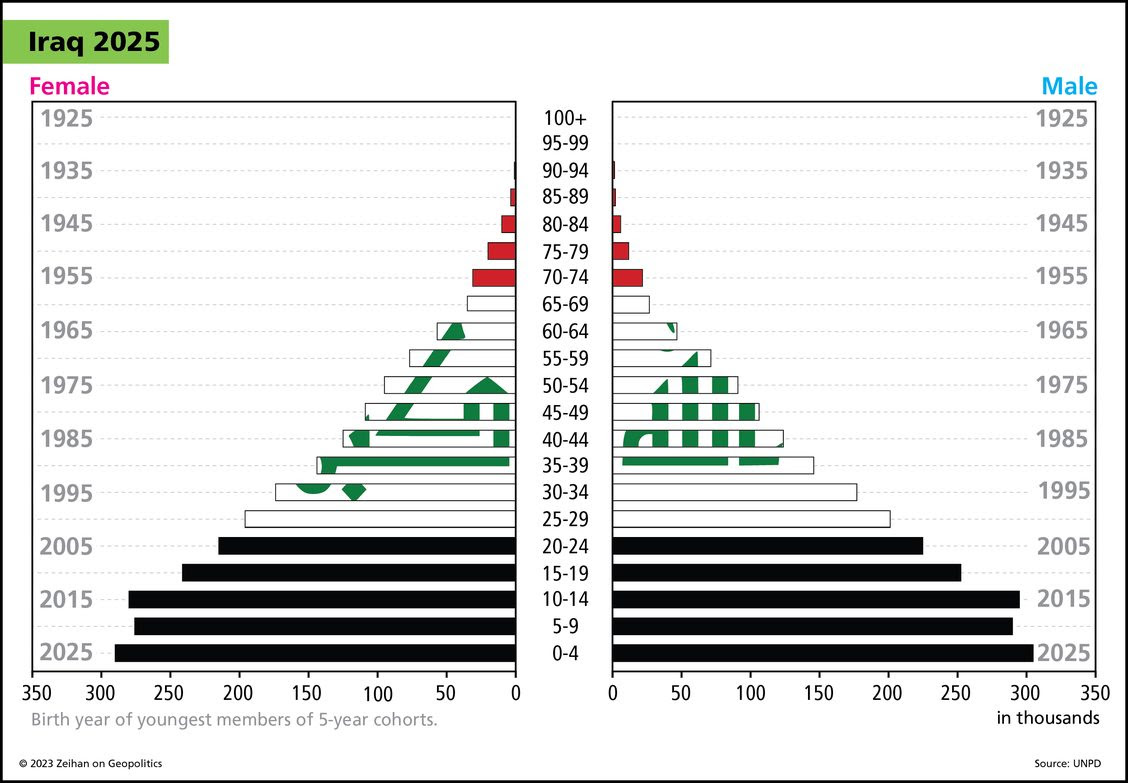

The Middle East doesn’t have a ton of moisture, so most populations remained relatively small and geographically concentrated. This kept demographics in the traditional pyramidal structure. Once oil was discovered, these populations had the money to industrialize. This enabled Middle Eastern populations to grow beyond the land’s carrying capacity.

As the population expands, you naturally have more mouths to feed. The only way to sustain a growing population is through imports and subsidies. While Middle Eastern countries have retained their pyramidal demographic structures, these populations have become increasingly unstable.

Since the Middle East is so dependent upon globalization, any disruptions to the global system could turn catastrophic. Combine a potential food crisis with wealth inequality and political instability, and the degree of civil breakdown in the Middle East could be devastating.

Prefer to read the transcript of the video? Click here

Here at Zeihan On Geopolitics we select a single charity to sponsor. We have two criteria:

First, we look across the world and use our skill sets to identify where the needs are most acute. Second, we look for an institution with preexisting networks for both materials gathering and aid distribution. That way we know every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence. Then we give what we can.

Today, our chosen charity is a group called Medshare, which provides emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it. Until future notice, every cent we earn from every book we sell in every format through every retailer is going to Medshare’s Ukraine fund.

And then there’s you.

Our newsletters and videologues are not only free, they will always be free. We also will never share your contact information with anyone. All we ask is that if you find one of our releases in any way useful, that you make a donation to Medshare. Over one third of Ukraine’s pre-war population has either been forced from their homes, kidnapped and shipped to Russia, or is trying to survive in occupied lands. This is our way to help who we can. Please, join us.

CLICK HERE TO SUPPORT MEDSHARE’S UKRAINE FUND

CLICK HERE TO SUPPORT MEDSHARE’S EFFORTS GLOBALLY

TRANSCIPT

Hey everybody. Peter Zeihan here. Coming to you from Milford Sound, one of my favorite places on the planet. Still in New Zealand. Today we’re going to do the most recent of the demographics series, specifically focusing on the Middle East. Now, the key thing to remember about the entire swath of territory between roughly Kuwait and Algeria. So that whole stretch – Northeast Africa, all the way into the Persian Gulf region – is that there’s not a lot going on from a moisture point of view. Most of these cultures are centered around oases or narrow river valleys. The Tigris and Euphrates in many places, the entire coastal plain is less than ten miles thick. And the coastal plain in places like Libya look very, very similar. Egypt doesn’t even have water on its coastal plain. It’s just the Nile. So you get these very, very dense population patterns on a very, very concentrated footprint. And the carrying capacity of the land is very, very low. And it wasn’t until the 1900s when you could introduce things like artificial fertilizer that you really got a very dense population even within that zone. So this is an area that was among the last parts of the world to enter the industrial era. And so you had kind of a classic pyramidal formation for the population density until relatively recently in their history.

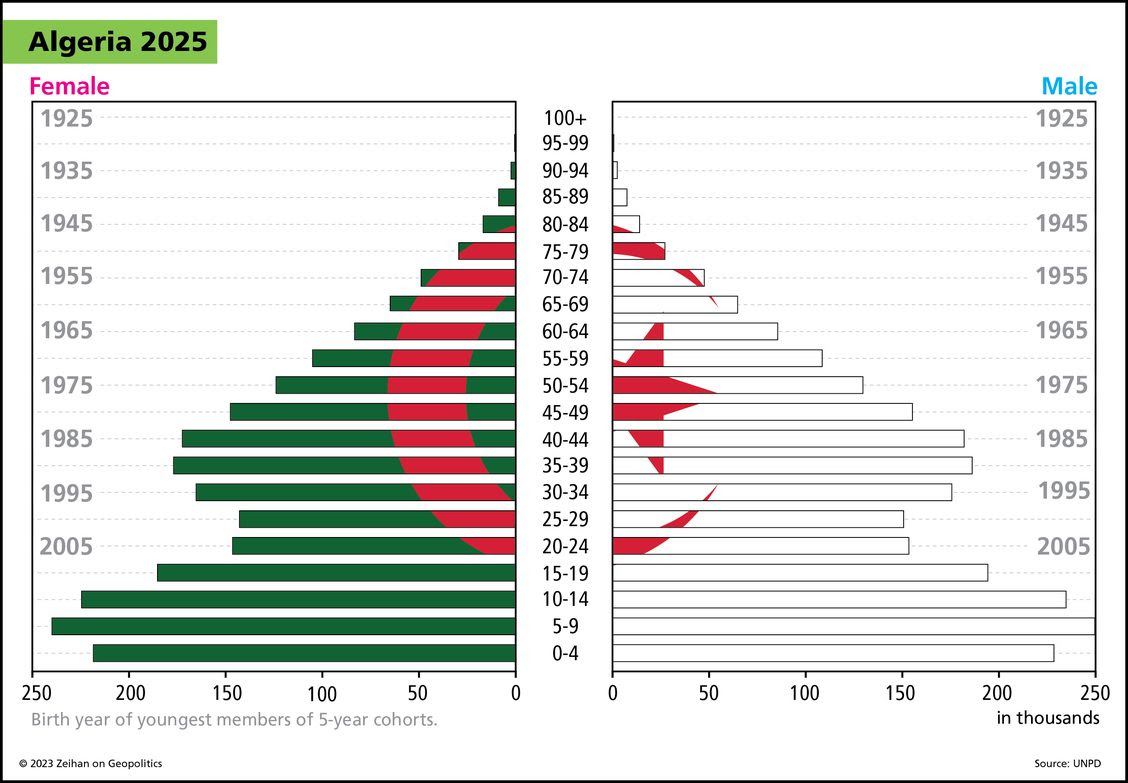

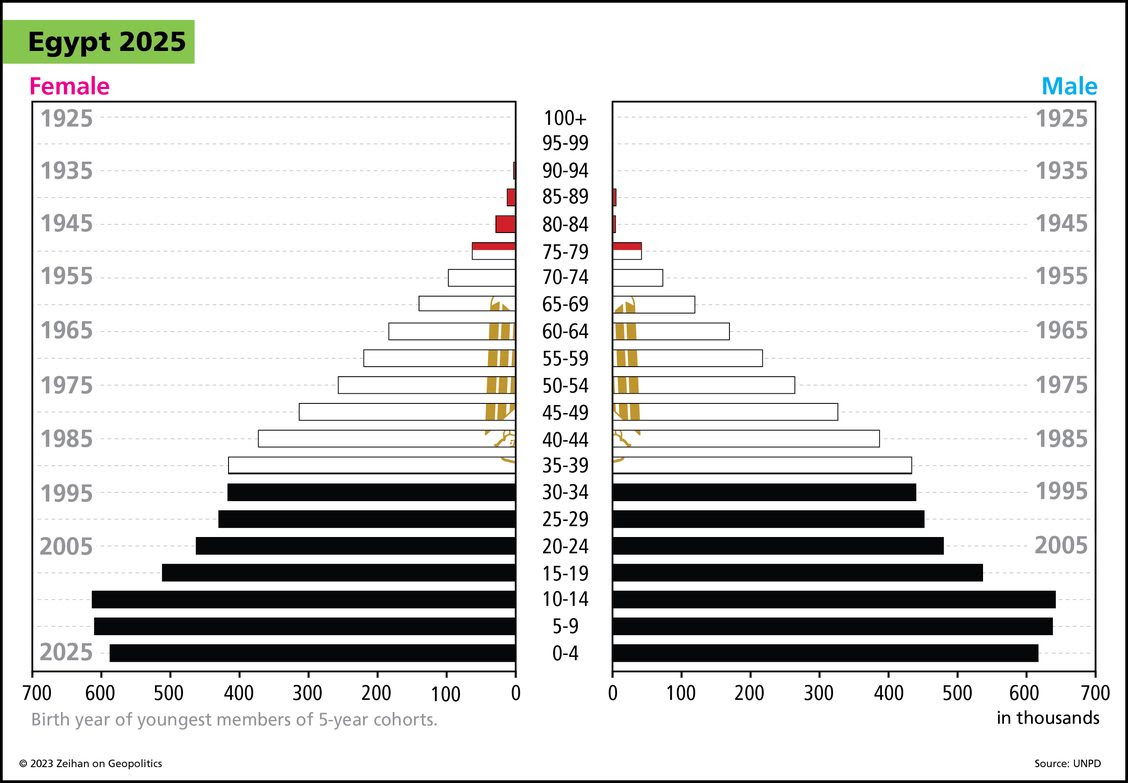

Okay. Where was I? There are some exceptions. In northern Algeria, you’ve got a much wider coastal plain. So agriculture is more favorable there. Obviously the Nile Valley and Mesopotamia, places that are still desert, but they have irrigation figured the places between the Tigris and the Euphrates Rivers. Obviously going back to antiquity. These have had a lot of people. But the general point when it comes to industrial agriculture stands, you can have a certain concentration and then you just kind of stop to be in the desert, which means that these are some of the last areas in the world to experience industrialization, artificial fertilizers, mechanized agriculture, that sort of thing. And so they don’t, they just have never historically reached the level of population density that you’re able to achieve in, say, the Western world or the East Asian world. Now, what that means is that there’s been a hard population cap on all of these regions up until today, until one thing changed. Oil, whether it’s in Algeria or Libya or Egypt or Iraq or Iran or Saudi Arabia. Once oil became part of the equation, the income potential for these regions expanded by more than an order of magnitude in some cases, almost literally overnight, certainly within a decade. And what that has allowed is these populations to expand beyond the carrying capacity of the land. In the case of Egypt, Cotton contributed well. So these countries could all bring in food and sell the oil to pay for it and then generate a very, very different population matrix.

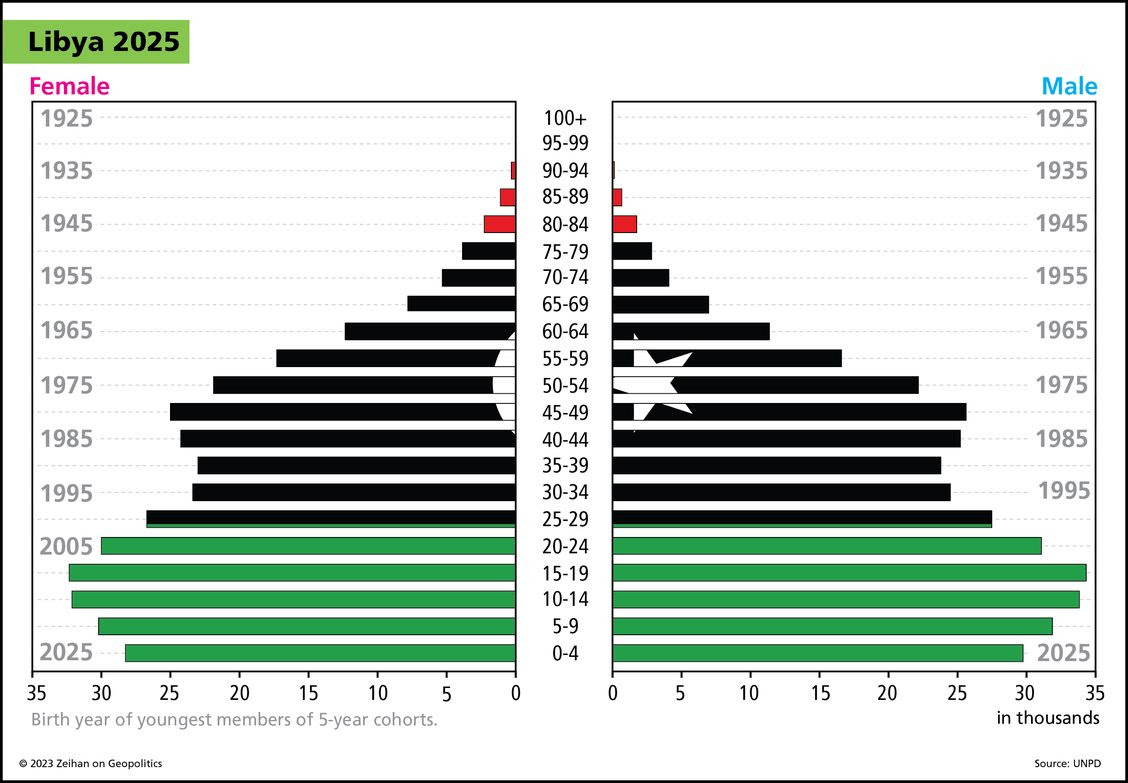

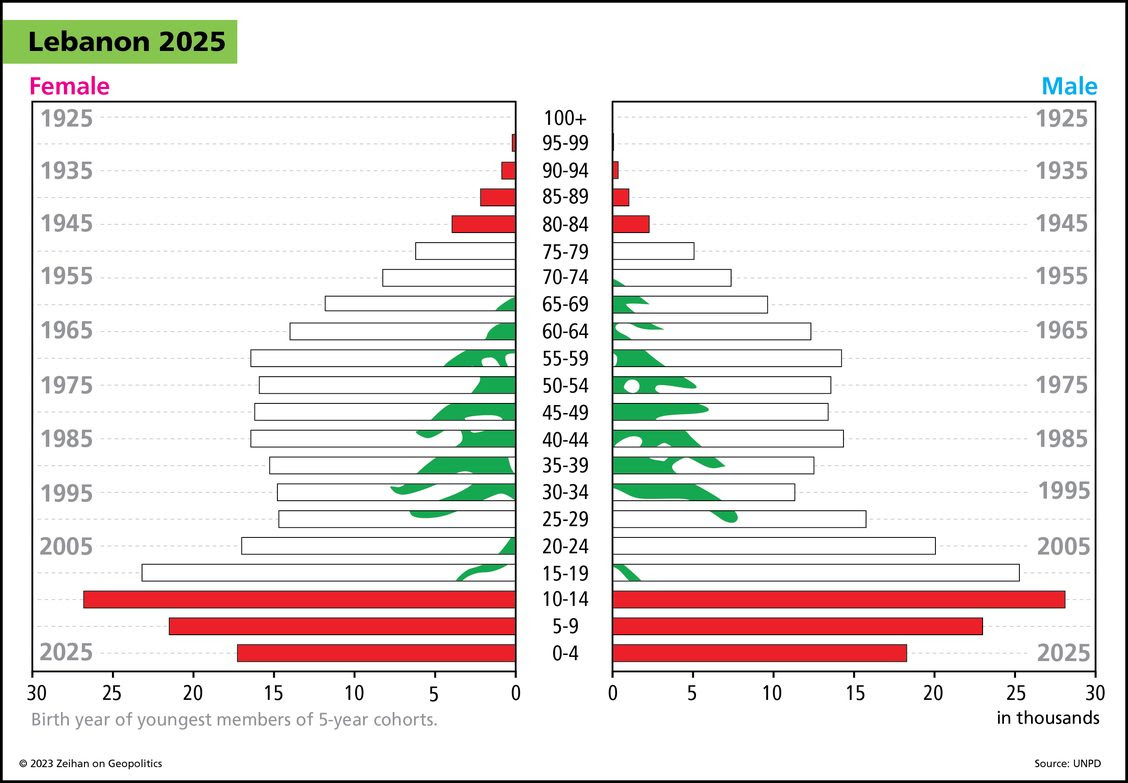

And we’re back. All right. So what this means is the countries have had it. All these places have a traditional pyramid going back to antiquity and then as we hit industrialization because of oil and the food just kept coming, they were able to maintain very high birth rates. They were no longer doing this with domestic food production, but instead with imported food. So the pyramid has stayed. It’s just gotten broader and broader, broader and broader because most of these countries have food subsidies in order to maintain political tranquility. But when the food is cheap, but you’re not producing it yourself, we get more and more people, but it eventually becomes more and more unstable from a demographic point of view. And now, whether you’re in Algeria or Egypt or Iraq, and especially in places like, say, Lebanon or Libya, you’ve seen the populations increase by a factor of four or five, even six or seven over the time since 1945, while food production has gone stagnate or in many cases like in Egypt, actually gone negative as we switched over to things like citrus and especially cotton. Which means these are the parts of the world that are now most vulnerable to anything that happens with globalization, because if anything impacts their ability to export their non staple food products and import wheat, you get a population crash. It’ll probably be worse in places like Libya, where food production has maybe doubled since 1945, but population has increased by a factor of seven or eight. And in Egypt, where a lot of the wheat has gone away and it’s been replaced with cotton and citrus since a population has boomed. And now, even if they switch all the food production back to wheat, you still would have a 50% shortage. And the ability of local food production in order to support the local population. So these places have seen some of the greatest expansions in population ever in human history and we’re not too far away from them experiencing some population crashes in human history. What we’re about to see as the global population sinks in is a degree of famine that is absolutely unprecedented and is likely to be even far more extreme than what we’re about to see people in china.

And so remember when you got a pure pyramidal population structure with lots of people under age 40, in that sort of situation, you’re going to have high growth because of the consumption, high inflation because the consumption and not a lot of productive capacity, because you don’t have a lot of skilled workers that are age 40 to 65. You also don’t have a lot of capital. And so these societies had a hard time lifting themselves out of poverty, except when it comes to things like oil sales, which is then usually the province of the state that doesn’t generate the sort of velocity of capital that is necessary for good infrastructure, for good education, and for all the other things that we kind of celebrate as the norm in the first world. It also means that you have a lot of young people who don’t really have a stake in the system because they don’t control the wealth that’s controlled by the sheiks and the princes at the top. So you tend to get very politically unstable systems. And if you add in the coming food crisis, the degree of civil great down that is possible in this, these areas are few. And for those of you who consider yourself students of history, if you look back and the rise and collapsed rise of cloud and the rising collapse of city states and empires throughout this entire region, this is starting to sound a little bit familiar. This may be where humanity got its start, but it’s also capable of some of the most catastrophic civilizational collapses. And we’re going to see that next decade or two.

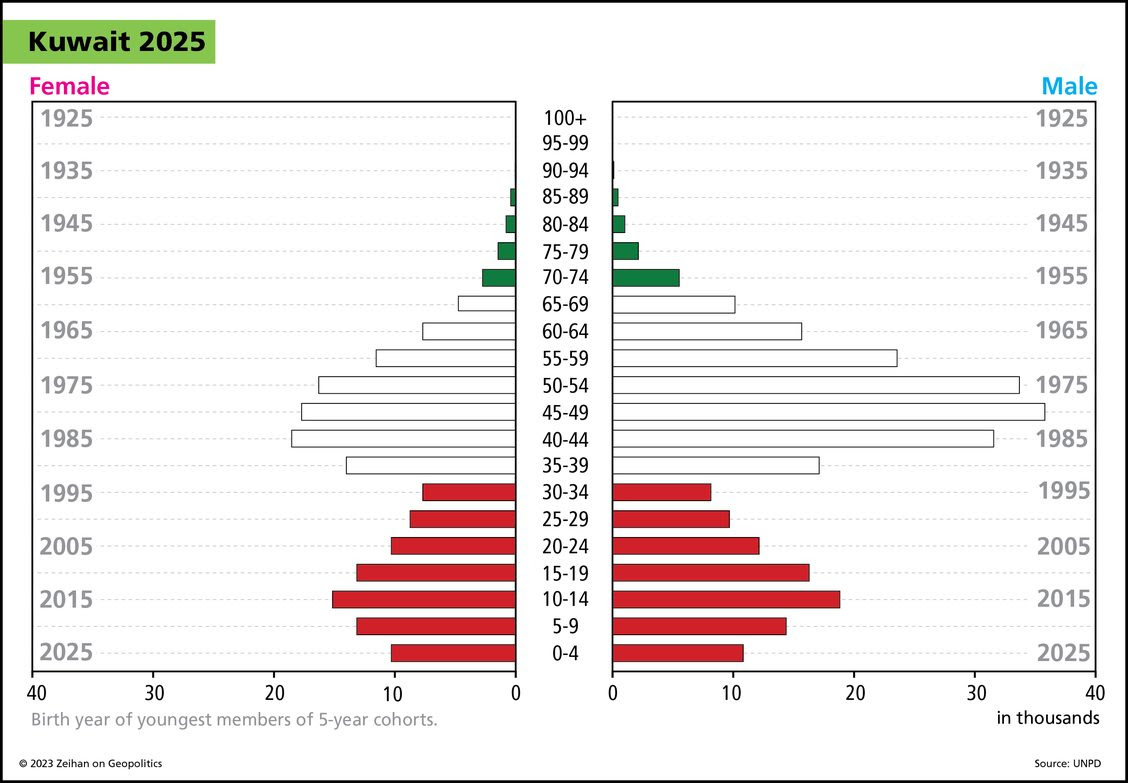

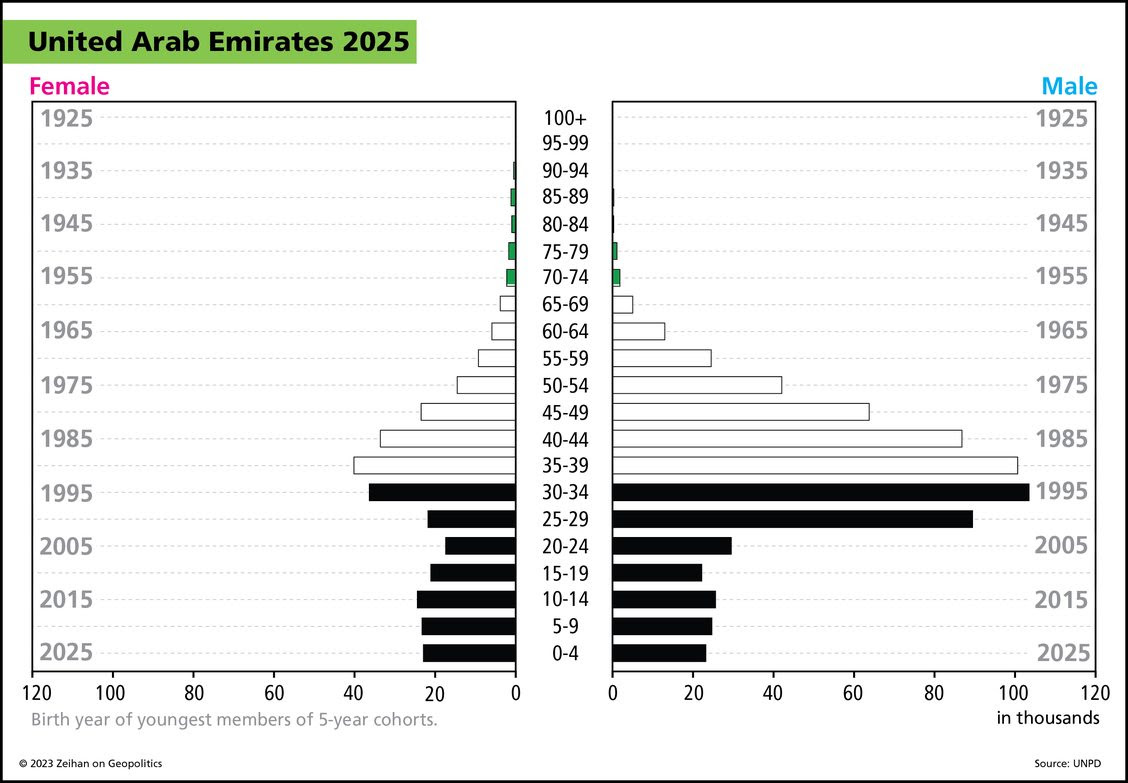

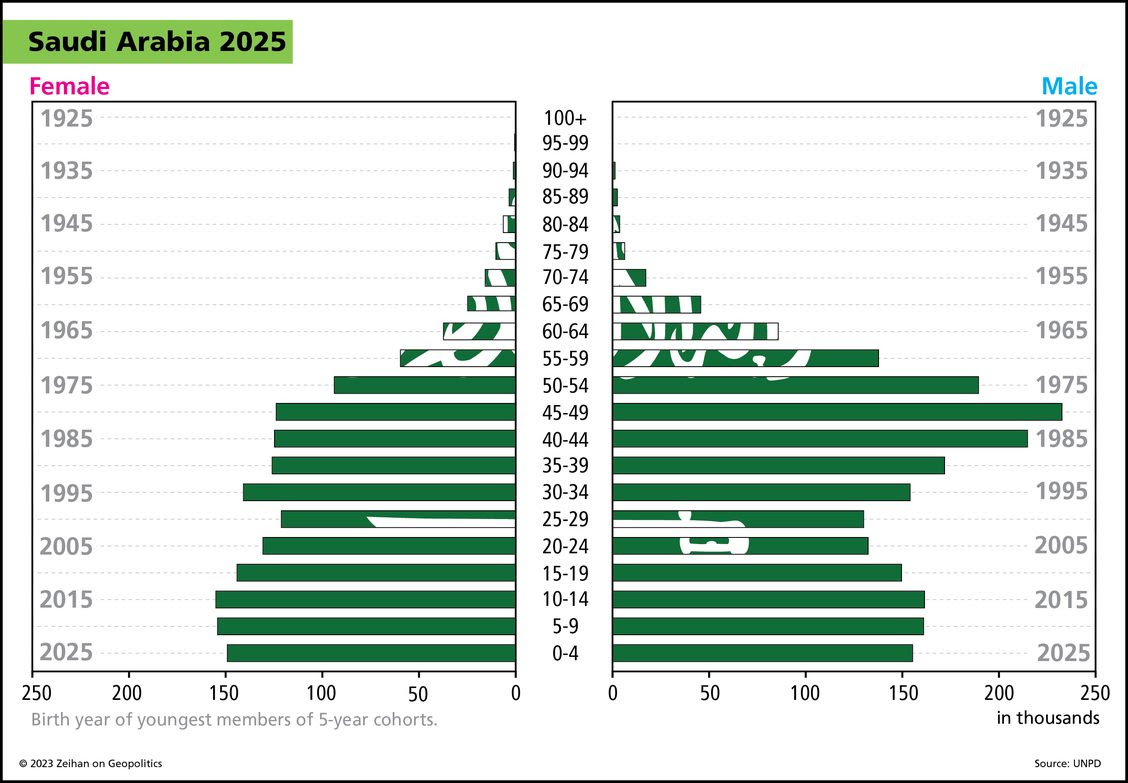

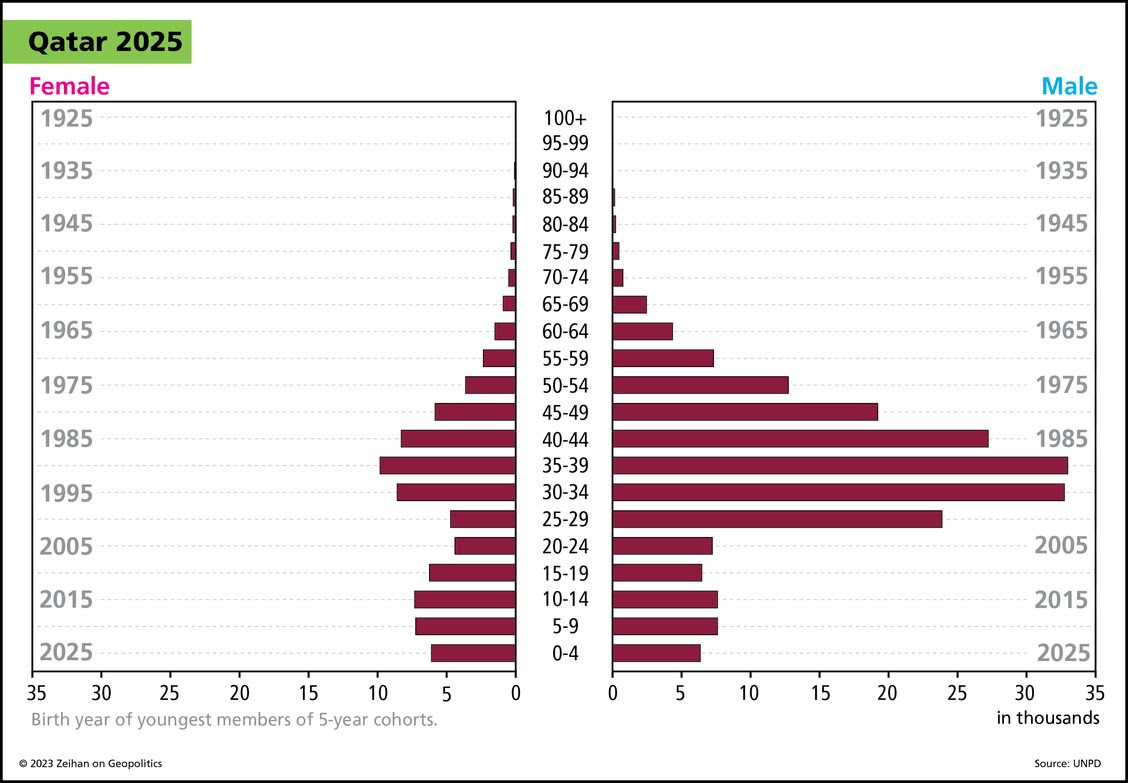

Oh, yeah. One more thing. On yeah we relocated to Te Anau. I know there is a unique demographic pattern for some countries in the Middle East that is largely based on their intense wealth, because once you get to a certain level of income, you start paying people to do other things. So, for example, if you’re in the United States in your top 1%, you probably have a housekeeper. Well, you carry that into the Middle East where you’ve got this oil and natural gas income and you’re surrounded by places with a pyramidal demographic structure, and you start hiring people to do everything. So it’s not just menial chores or raising the kids. It’s building roads. It’s building bridges, it’s doing your oil infrastructure. You bring in labor for absolutely everything. And so if you look at countries such as Saudi Arabia, Qatar or especially the United Arab Emirates, you will notice that they have a pyramidal demographic structure. But on the men’s side, between roughly age 15 and 40, there’s a huge bulge that goes out, which is in essence, foreign guest workers who for the most part, unless you’re on that top end, it’s like doing the air traffic control and stuff, basically slave labor.

And in some cases that is not just a significant percentage of the population. In the case of Qatar, that is like half the population for the UAE, almost three quarters. So when you’re looking at the geopolitics of the region, you’re like, Oh, you don’t like the Iranians or We don’t like the Iraqis. Just keep in mind that the countries that the Israelis and the Americans, to a certain degree have identified as potential allies of the future Saudi Arabia, Qatar, UAE.

You are dealing with slave autocracies. So have fun with that.