Hey everybody. Peter Zeihan just taking a walk after this guy dumped on us. The big news today, it’s February the fifth, is that overnight local time. Iranian backed militants in Syria attacked another U.S. base. It’s the first significant attack since those three American soldiers were killed early part of last week. And the United States launched a bunch of retaliatory strikes against Iranian backed militias throughout the region.

Anyway, this is the first significant action by them since. And again, it looks like a drone got through and hit the barracks again. This time it wasn’t American servicepeople who were killed, but a half a dozen Kurds that U.S. Special Forces were training. Let me explain how we got into the Middle East and why it’s difficult to get out.

And then we’ll put this into context. So I’m going back roughly very roughly a thousand years. The Middle East has not been a place that anyone wanted to be. It was on the way somewhere. So you had your more advanced somewhat very loosely using this term technocratic societies with little higher value add in their economic systems in the West.

And then you had East Asia and to a lesser degree, Southeast Asia and South Asia that produced goods that you could not find in the West, things like spices and porcelains and silks. And so the trick was to figure out how you could link these two economic systems together. Despite the vast distances involved, and from roughly 1000 to roughly 1500 A.D., the solution was coastal vessels, camels, caravans.

The problem with all of those things is you had to go through any number of intermediaries, especially for the land routes. And since the Sea Rats weren’t safe, most people stuck with the land routes. This meant that the folks who lived in between in the middle to the east of the Western nations or go the name found themselves having to pay massive markups because you’d send your go east and you’d bring the cargo west.

And every few miles or a few dozen miles, there’d be another middleman who would take the cut. And so the cost of these products didn’t double or triple or quadruple, but typically went up in cost by a factor of a thousand or so. And so what became what were not necessarily everyday goods, but not exactly considered exotic goods out east became the the cream of the luxury goods in the West.

And so the trick was to how do you how do you avoid those markups? The solution was set upon by the Spanish and the Portuguese, who developed the technologies to sail farther from the sea excuse me, far from the shore with old coastal vessels. If you happen to anchor, which you had to do every night within sight of land, there is a reasonable chance that somebody who lived in the neighborhood was just going to come and take your ship and kill your people and take all your stuff.

So that’s one of the reasons why they tend to prefer the land routes. But with the Portuguese and the Spanish developing deep water navigation, they were able to do an end run around that entire thing, interface directly with the East. And so from roughly 1500 until roughly 1900, the Middle East just didn’t matter. It became a complete backwater and eventually the Western countries industrialize.

And when they came back to the Middle East, to an area that had not industrialized, you know, you bring a knife to a gunfight enough times and the locals pay attention. And so you basically had the Brits, the French and the rest divvy up the entire region into mandates and colonies. Now, why was the West able to pull that off when the Middle East just kind of stayed at the same technological level?

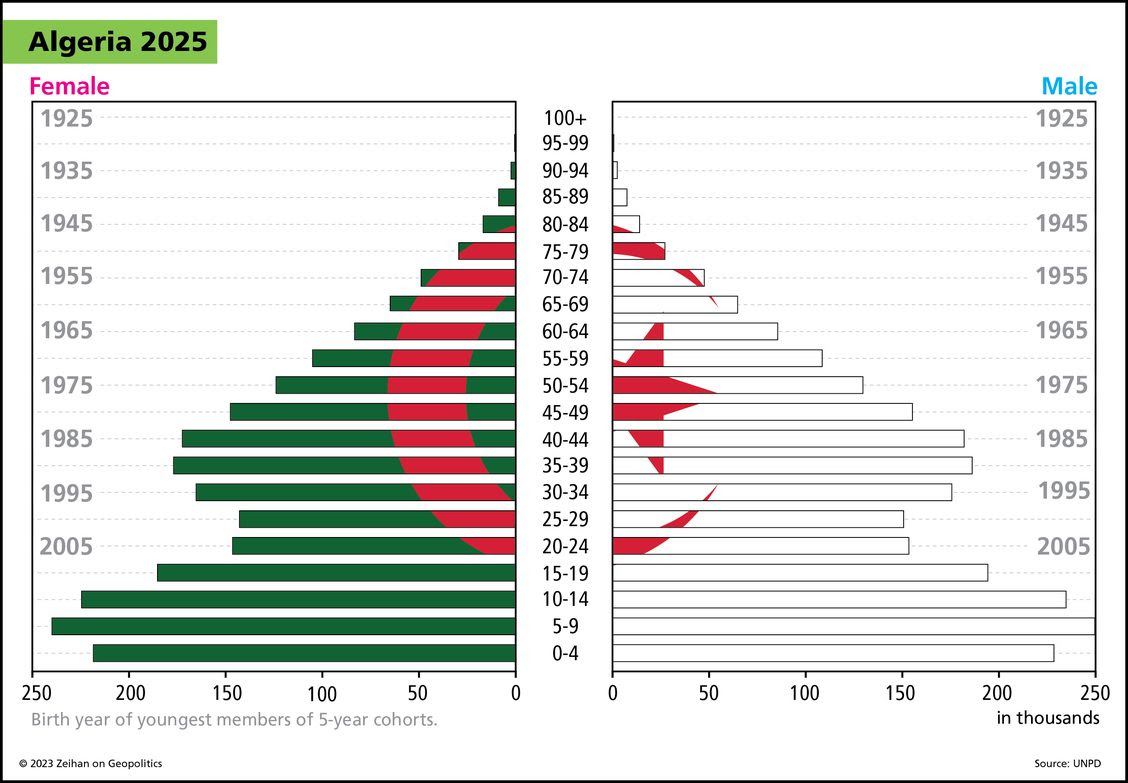

And to be perfectly blunt, the answer is rainfall throughout the Western countries. In Europe, it rains. Rain means that you can grow crops in any number of areas. And if that gives people an interest in pursuing their own economic destinies. Also, you had winter in most of those areas. So in the off season, farmers could be working on something else.

They weren’t exactly getting law degrees. But the point is the overall skill level of the population steadily creeped up. And when you’ve got a lot of people who are invested in stability in the system, even if it’s not a democracy, you get a degree of political stability, economic advancement, technological acumen that you just don’t get in the Middle East and the Middle East.

Very few places have rain where you do have water. It’s in a relatively narrow band either right on the coast or along a river that makes it very, very easy for a political authority to rise and dominate that specific geography. And in doing so, basically you reduce the entire population to slave status. That does not give people a lot of interest in pursuing stability for the system makes revolutionaries very popular.

But it also means that the power of the state is just almost total, making it very, very difficult for anyone to make something of themselves. So you will get centers of learning throughout the Middle East who did absolutely preserve the Western knowledge during the Dark Ages, but they never applied it themselves. They never disseminated it with her in their own cultures.

They were basically just libraries maintained by monks. Oversimplification. 100 years of history. I recognize that. But you can’t deny the economic trajectory of the Middle East versus the West. And then once the West cracked the code on industrial technologies and they started having gunpowder and cannon and the Middle East was left behind, there is no contest at all.

So now today, the economies of the Middle East matter more to the world today than they have for most of the last half millennia, largely because of oil, because there is an asset those industrial economies need in order to function. Now, this isn’t so much an American problem directly because North America is self-sufficient and not even self-sufficient in oil is a significant exporter of oil.

And if the Middle East were to vanish tomorrow, we’d have some adjustments on things like crude quality. But within a couple of years would be totally fine. However, the Europeans significantly less so specifically since the Russian crude is no longer part of their equation. Parker Now, where does that bring us? Well, it means that anyone who goes in the Middle East after about 1950 is faced in a very different environment from what was faced from 1008 to 1500 when it was just a place you had to push through or from 1500 until roughly 1950 when the West was industrialized.

But the Middle East wasn’t. Now, the Middle East is, and no one’s going to say that a group like ISIS in Syria is like the pinnacle of human technology, but it’s really easy for them to get explosives and AK 40 sevens. So it’s no longer a contest like we saw from 1919 50 between an industrialized Western imperial system and a completely non industrialized, almost tribal Middle Eastern system.

You’ve got a different makeup now. Now, the governing systems of the Middle East themselves are also in play and very much in flux, because before 1950, you basically had a series of what could be best called Fortress Political Systems, where by dint of geography, you know, maybe they had an oasis like Damascus, maybe they were surrounded by desert like Egypt, maybe they were a mountain fastness like Iran.

It’s a little difficult to get in and out. And some of these areas are a lot more difficult to conquer than others are around really being at the top of that list. But you introduce industrial technologies to this area and the post-colonial post-World War two environment, and all of a sudden they’re not just drilling for oil. They’re building roads.

They’re buying military hardware. And it makes for a very different mix. You get this incredibly brittle, top down, concentrated political system that is absolutely in hate bubble of providing the people with the level of technological progress that is possible elsewhere in the world, because there’s very little to work from aside from cash from oil. And you apply that in a world where society is weak as well.

And the result you get lots and lots and lots and lots of militant groups. And if you want to back one versus the other or one versus government, that’s fine. But even if you win and the militant group overthrows the government, well then what you’ve taken what little order exists in an area and it’s turned into chaos. You get a complete societal breakdown, as we’ve seen in places like Egypt and Iraq and Syria in recent years.

So enter the United States in the aftermath of the 911 attacks. The Bush administration felt that the best way to fight al-Qaida was to make sure that the countries that allowed okay to function would go after it. So after the Afghan operation, we discovered that al-Qaida scattered to the winds, and we found out that a lot of the recruits were coming from Syria because that was how the Syrians got rid of their own dissidents.

A lot of the troops, Taliban troops that were in Afghanistan fled through Iran to parts unknown because the Iranians were like, Well, we hate these guys, but we don’t want to deal with them, especially since they don’t like the Americans very much and then the Saudis necessarily the government itself. But a lot of elements within Saudi Arabia were part of the ideological and financial underpinning that made Al Qaida possible.

How do I know that? Because we allied with them back in the eighties to form the Mujahideen, which eventually became the Taliban. Anyway, so the U.S. is looking at this region, Syria, Saudi Arabia and Iraq 12th partner. And any of them wouldn’t be fun conquering all three at the same time to get after a militant group just doesn’t seem like the right task.

And so the solution that was struck upon was to knock over Iraq and occupy it with armored tank brigades, which is not the way you pacify a population. You want ground infantry for that. The idea is Tehran and Damascus and Riyadh. None of them thought the U.S. was going to do this. And so when it did it with tanks and left the tanks there, they’re like, shit, There’s nothing to stop the United States from turning on us.

And while Iran was, to a degree protected by its mountains, they had a little bit more confidence would be able to put up a good fight. The other two had no such confidence and they knew that if the United States decided to come for them that their regimes were done because there was no civil support, there was no technical competence, there was no cohesion.

Well, it worked. And those three, three countries went after al-Qaida for us and are the primary reasons The strategy is the primary reason why Al Qaida is, for all intents and purposes, no more problem is that we didn’t declare victory and went home. We tried to make Iraq look like Wisconsin with the results that you can imagine. Because, again, there’s nothing to build from in terms of society.

We overthrew what stable order there was and replace it with nothing. Now, fast forward to today. The Bush administration felt they had no choice but to go in. And, you know, we can debate whether it worked out well or not. First phase of the plan I think worked. Second phase, Obama changed nothing. Despite his rhetoric, Trump said he pulled out but left troops in places like Syria to fight ISIS because no one no one in the US political system wants to be blamed for being the guy who allowed that militant group to come back.

But here’s the problem. The countries in these areas are never going to have the foundation that’s necessary to form a country in the way that Americans or Westerners in general or even Asians see it. And so if your goal is to prevent the creation or the operation of the resurgence, the specific type of militancy, you will be there forever.

And that’s one of the reasons why we call them the Forever Wars, because we found ourselves going to war with a military tactic as opposed to any specific group. And while most of our troops are out of the region now, what happened earlier today in Syria is the best that we can hope for. Unless the strategy changes, we are never going to be able to turn these countries into something that we would normally recognize as a peer or is even someone in the same category as the nation states that we have in most of the rest of the world?

That’s not how these areas work. They never have. They don’t have the economic geography to try. And so we’re left with a fun little discussion. We have to have option A is stick it out forever, do what most of our forces have been doing in the region since the operation was slimmed down under Trump and hunker in your bases and watch and if something like oasis bubbles up again hit it with a hammer.

Go back to your bases and watch some more. And if you do that, you’ll be there forever. And while you’re there forever, other militant groups who have their own ideas of who should be in charge will take potshots at you. And that’s what we’ve been seen with the Iranians being the instigators. This is the new normal. This is the old normal.

This is just what the region look what’s option to leave from a casualty point of view. It’s easy. We’re never going to make this area look like something that we want. Danger if you leave. Is that a group that you specifically don’t like is going to boil up? Now, let me put that into context. Part of the reason that we’re still there is we find the tactics of ISIS beyond repute.

And we’ve seen that replicated in Hamas in the beginning of the Gaza war. We’re not going to be able to defeat a tactic. But the fear is, is if we leave, more of these groups will boil up in a shorter period of time and eventually start not just attacking the locals, but our interests in the region as well.

The problem with that theory is that it assumes that there’s something better that can happen if we stick around. Something to keep in mind, this is an area, a fortress cities. And historically speaking, when you don’t have an external power like the United States in those fortress cities, start to enforce their own writ on the area. Now, we have enabled Baghdad to recover from the Saddam and the occupation areas, and it’s doing a pretty good job of holding its own.

What we’re doing against groups like ISIS is basically taking some of the unknowns out of the equation for the other two major powers in this region, which are Damascus, Syria and Turkey. If the United States were to vanish overnight, they would have to deal with these unknowns themselves and we would have a much more aggressive effort from both countries to deal with groups like like ISIS.

That is more normal. And so we’re actually in this weird situation where U.S. forces that are remaining in the region, even if they’re just staying in their camps, are actually have become the single greatest reason why the government in Damascus still exists, because under normal circumstances, other regional powers would have moved in and smashed these groups that were patrolling out of existence.

And that means the Turks get more involved. That means the Syrians get more involved, and that means the Israelis get more involved. And in that sort of contest with Mesopotamia kind of acting as an anvil, we probably see the end of the Syrian government within five years. Of course, it would be bloody and horrible because this is a region that can barely grow food itself and it uses a lot of those energy imports or exports to buy food that it imports.

So the capacity here for an outright civilizational collapse is very, very real and agreed. The presence of U.S. forces is one of the few things holding the darkness at bay. Now, whether that is considered an American national interest or not, talk amongst yourselves.