Hey everyone. Peter Zeihan here coming to you from the southern headlands of the Wanganui Inlet on the northwest coast of New Zealand’s South Island. Today we are taking a question from the Patreon page on, demographic specifically, that I talk about Gen-X and the boomers, the millennials and all that of the United States quite a bit. What about the generational blocks for other countries, specifically Iran, China and Russia?

There’s a little bit of a danger here because all demographic lines are a bit artificial. So the ones I use for the United States, specifically people who were born between 1946 and 1964, in the United States. Those are my boomers. These are people who were, born in the post-World War Two boom years in very large numbers.

And as they went through their childhood and adult lives, they’ve basically remade American culture in their image after them. 1965 to 1979, roughly. You have, Gen X. That’s my generation. Birthrates dropped off precipitously. One of the reasons the boomers were so many is you still had some old gender norms. By the time you get to Gen X, their parents had become a little bit more, I mean, the female revolution happened in there.

Dropped the birthrate a little bit. The suburbs had already been largely populated, dropped the birthrate a little bit, raised cost of living. Drop the birthrate a little bit, a little bit. Energy prices, all that good stuff. So Gen X until recently, was the smallest generation in American history. After that, you got the millennials born roughly 1980 until 1999.

These are the kids who had never seen or remember seen a, circular phone and basically were the generation that made the transition to a digital world. And then the Zoomers, kids who were born since 2000 are the ones who were, doing penpal emails rather than written correspondence and have never looked back. All right. Like I said, it’s a little artificial.

Whenever you’re looking to another country, you need to look at the gross economic trends, and physical conflicts that have shaped their worlds, because oftentimes you’re not going to draw the lines in the same place. So, for example, if you’re going to look at Europe, there is a boomer generation in about the same window for about the same, reasons, but because the cost of living was so much higher and because Europe is so much more urbanized.

They didn’t have a lot of kids. So American boomers had the millennials, the European boomers did not. And so the demographics just kind of fall apart after the 1960s. So you got to be careful about how many trendlines. You try to extend. So, for example, in the case of the Russians, the really definitive break is pre and post Brezhnev for when your adult life was because if you were born and had a memory of Brezhnev years, you remember how bad central planning can be and you were probably a little bit more open things like perestroika and glasnost.

But then when you get into the post-Soviet system, you got an equally bad thing to compare to. So Brezhnev, stagnation, economic doldrums, post-Cold War collapse, democracy for you probably equals chaos. And so you’ve always known that there’s or always felt in your gut that there’s a choice between stagnancy but stability and opportunity, but free fall. And it’s not a pretty choice.

But if you were born just a little bit later, then you have no political memory of life under the Soviet Union. You may remember the free fall of the 1990s, but then for the next 25 years, Vladimir Putin, despite his many, many, many flaws, has been leader. And Russia has been relatively stable from an economic point of view for that entire time, and especially if your first adult memories are post 2000.

You don’t know a life without Vladimir Putin. And yet that’s everybody under age 40 in Russia today. So it’s not really a boomer or millennial zoomer kind of thing. It’s a Brezhnev issue. It’s a Putin issue. It’s a fall of the Soviet Union issue about where you draw the lines. Now, something to keep in mind is the freshness generation was the last one to really have kids in numbers.

We had a little blip during perestroika when people thought that the Soviet Union could be reformed, but it didn’t last. And since then, the birthrate has just been awful. So the generation that has been growing up since 2000, in Russia, you know, the the millennials and the the Zoomers of Russia, if you will, are really the last generation that is going to exist and significant enough number to make anything happen in Russia.

And so what they do from their small numbers will shape a large part of a continent for the rest of the century as they die out. All right. What else? China. Hu. Okay. China. It’s a little bit simpler. It’s pretty. And post one child policy. If you’re born before the one child policy kicked in, you know, famine, you know, a lack of electricity, you know, outdoor plumbing, and you know that the world can be a very nasty place.

You also know political leadership that is murderous and mercurial. And you yearn for something better if you were post one child, not only was there a floor put under the chaos, but the internationalization of the Chinese system after Mao, generated a degree of economic opportunity that had never existed. Now, part of this is indeed policy, because it was after Mao that you got things like roads and electricity and meaningful amounts of steel and high rises and health care and all the other things that go with modern life.

But having only one child means for grandparents support, two parent support, one grandchildren and those grandchildren. The people who were born in the later decades, you know, 1990 and after, they have no nothing but an economic boom because all of the wealth of the country has been focused on industrial expansion, and there has not been a large generation from below that needs to be clothed, fed and educated.

So all of the social spending that was done in China was spent on very few people, relatively speaking, and you were one of them. So for young Chinese, it’s been glorious until the system started to break about seven years ago. And now we’ve got all the worst aspects of capitalism, things like, conspiracy theories throughout the public space, massive amounts of shell games, real estate booms and that have not yet gone bust.

Putting the money into the wrong things over investment, but no longer investment that generates growth when you do investment on the front end, when you don’t have roads or power lines, you get roads and power lines, and that’s great. But if you start with roads and power lines and you do a lot of state investment, you’re just building more roads and power lines and you only need so many of those.

So the lesson that the Japanese learned in the 1990s and 2000, the Chinese have now learned it as well. And so the Chinese need to adapt to a new economic model, but they’re still dealing with the distortions of the old capitalized, over invested system. So if you’re a 20 something Chinese citizen today, you’re of a small generation.

You hear the stories from your parents about how good things got, how fast it got, how stable it was. But everything has too much money chasing too few goods within the country, and everything is too expensive. So your chances of ever starting a family are nil. Your chances of ever being able to afford an apartment, much less a house, are almost nonexistent.

And it’s a very different political view. And if you were to put a label on it, these would be the zoomers of the Chinese system. And they are the last generation that will grow up in a centralized China, and they will definitely have some visceral memories 20, 30 years from now about how the Chinese system crashed around them.

And no one could seem to do anything because the political system is too ossified to function. Those people are going to be making some very interesting political and personal decisions as the system fails. Because if there’s anything we know about Chinese history in the past, when the center breaks, people leave if they can and a country that has at least 800 million people, that’s like the low end for estimates and maybe as many as 1.2 billion, if only 5% of them get out.

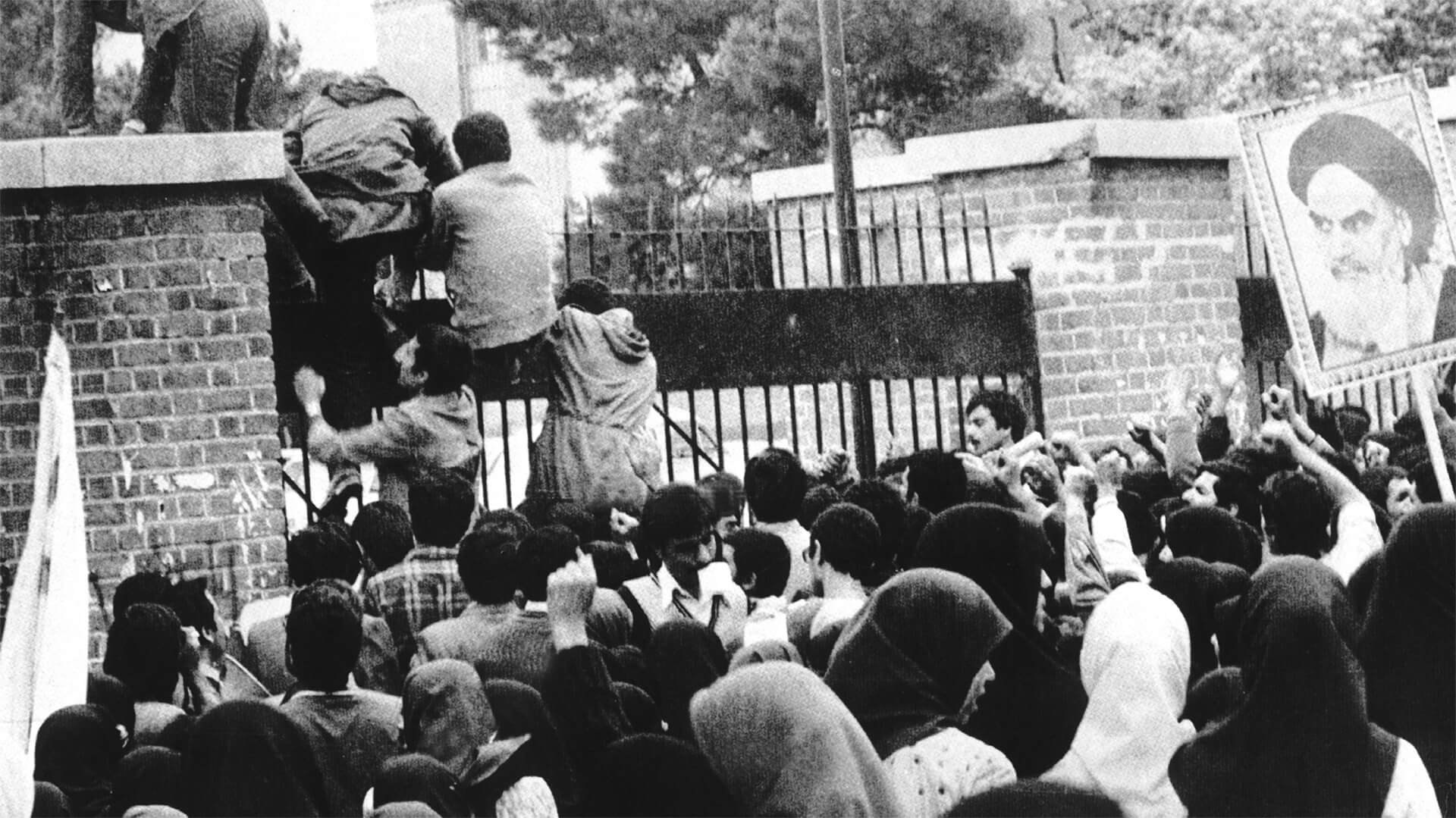

You’re still talking about the greatest migrant surges in human history. All right. That just leaves Iran. And Iran’s is even simpler. Yet it all depends upon how old you were when the Shah fell. And the mullahs took over and close to the water here. We’re going to turn around. There we go. Okay. This is just a really cool pocket beach.

I found. You practically have to repel down to it. Okay. Iran. So if you were are old enough to remember Iran as an adult before 1979. So you’re in your 60s for this category. The boomers, if you will. You remember just how corrupt the Shah was, but how there was opportunity for anyone with an education up to and including women.

And then the Shah fell and the mullahs took over. Women were disenfranchized and the intelligentsia and the engineers and everybody with a set of skills who could left the country. The people who left the country tended to have the money, and they emptied out the inner cities. Sorry. Inner cities in Iran, not the same as inner cities.

And like Chicago, you’re they emptied out the wealthier parts of Iran’s cities, took their money, took their kids, took their skill set and left. And you had a 15 year period where Iran was basically drowning and an inability to function because it didn’t have the skill set anymore. It had lost most of its educated youth, and most of the efforts the Iranian government, past and present, had made to educate another generation left the country and instead they had eight years of a grinding war with Iraq.

And after that, a series of on again, off again confrontations with the United States. Now, if you fast forward a little bit to a break point of around whole 2008, 2010, you had a shift in government with, the rise of a guy by the name of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad or a dog, as we used to call him at my old job, and a man at a job, was the first leader of Iran who was not a cleric since the fall of the Shah.

And he was deeply conservative, and he was deeply anti-American and anti-Western. But he wasn’t a man of the cloth. And he thought there should be room in public life for people who didn’t go to seminary, to be perfectly blunt. And so there’s now a split in Iranian society between the mullahs. On one hand, these conservatives who are, secular on the other hand, and then a wider disenfranchized group who has to basically take whatever’s on offer.

And that has made the country significantly more politically unstable. And in light of ongoing hostility with not just the United States, but the Western world in general, significantly less well off, because one of the mistakes that Ahmadinejad made is in order to get people over onto his side versus the clerics, he just bribed everybody. And so the state budget exploded, debt exploded, the currency crashed.

And then when a new round of sanctions came in and they could no longer underwrite everything, it all went to hell. Now we even have the strategic steps that the Iranians have taken to spawn paramilitary groups around the world falling apart. And so all of the money that Iran has spent on political consolidation, political evolution, education and increasingly strategic cost have all gone to nothing.

And so if you were 20, 15 years ago, for the last 15 years, your entire adult life, you have simply seen one state failure after another out of Tehran and you start to get a little pissed off. I’m not going to say anything simplistic like Iran is poised for a revolution or is ripe for change. What I’m saying is that the old pillars of stability that allow it to function don’t exist in the young adult generation, and that is a very nasty combination of factors.

Because remember when the old people who lived under the Shah left, they took the kids with them. We had a 20 year baby bust in Iran. So this younger generation is Disenfranchized is angry and is poor, relatively speaking, to Iran’s long history that that can turn violent very, very quickly, even if it doesn’t generate political change. So bottom line, there’s a generational story everywhere, but in before you can tell it, you have to really look at the local history and the economic trends that have shaped the people have grown in that areas.

It’s not going to be a cut and dried. It’s going to be different everywhere. But there is definitely lessons to learn. Okay. That’s it.