If you’ve followed me for a while, you’ll know that I take my travel very seriously. Unfortunately, it seems that my work keeps crawling its way into my personal life, because deglobalization is changing tourism as we know it.

Global tourism will decline; I suppose that’s a no-brainer if global trade and relationships start to breakdown. But the collapse of China could have an outsized impact on the developing world and tourism to these countries.

India is poised for long-term success, but the coming years will likely be much more unstable, making tourism in India less appealing in the coming years. Brazil is a country heavily integrated with China, and if that stops, the Brazilians will be looking at economic and social collapse. Which means Brazil will also be much less attractive for tourists.

Transcript

Hello, Peter Zeihan here. Coming to you from arches. Today, since I’m on vacation, kind of, we’re gonna talk about tourism. The places you need to go while you still can. We are going through a period of massive economic change globally where demographics are basically smashing the old model before you even consider what’s happening in the United States with the globalization and populism.

And the end result is there are a lot of countries that people like to think that they want to visit that aren’t going to be options for much longer. So the point of this video is to give you an idea of where you should prioritize, because time is very, very limited.

All right. Quick reminder of what everybody is up against with globalization. Global trade is obviously going to collapse. That reduces access to things like finance and energy and food products. And so you’re looking for long term stability for a place does it doesn’t have the, the beauty that you’re after, physical or cultural, whatever happens to be, but has the ability to maintain a degree of stability itself.

Big part of this is going to be when China collapses, which is not far off. A lot of the Chinese money that has been flooding into specifically the developing world to fund things, is going to go away. Keep in mind that a lot of the things that Chinese are funded were never funded before, because they were not necessarily great investment options.

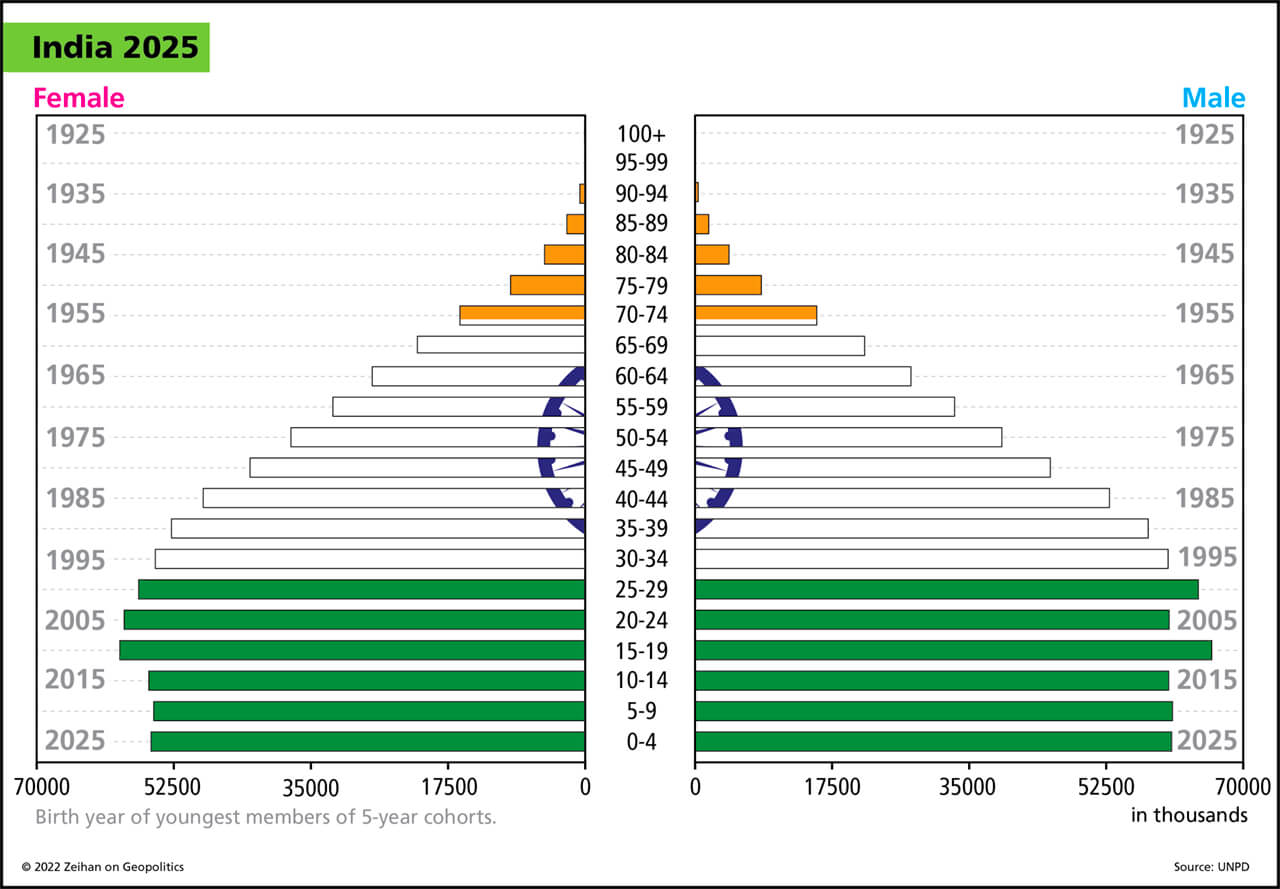

The Chinese view money as a political good. That’s why their money supply is so huge. Anyway, first country we have to talk about is India. India is a country that overall, I think is going to come out on the positive side of the globalization trend. But India is a big place with over a billion people. And to think that they’re going to go through a massive industrialization process that’s going to double their industrial plant and adapt to the collapse of China as a source of consumer goods and collapse to the international trade system, which has allowed them to reach out, without massive social upheaval, is being overly optimistic.

India will still be there. India is actually probably going to be entering one of its greatest growth periods in its history, and India has been around a long time, but they’re going to be a lot of growing pains, and that’s going to generate a lot of social stress, which is going to change the profile of what you would do for tourism in India.

Next up is Brazil. Brazil has a lot more exposure to the trends that are coming, and it’s a very high dollar producer for agricultural commodities because it needs so many inputs, most of which come from a different continent. So if anything happens to globalization, they lose access to those inputs on a reliable basis, and a lot of the land goes follow because it just has no innate fertility.

In addition, they suffered a double blow from the Chinese number one. They’re one of the top investment targets for the Chinese who are trying to get that agricultural product to China. And without that investment, you should expect infrastructure spending to basically come to a standstill. And secondly, back in the 2000s under the Lula government, the Chinese formed all kinds of joint ventures with the Brazilians, which basically meant that they went into Brazil to set up joint production facilities, but they stole absolutely everything that wasn’t locked down, most notably, the intellectual property took it back to China, produced it at a bigger scale, and drove all of Brazilian industry out of business. So Brazil today has basically become a two horse economy, high cost agricultural product, high cost, industrial inputs such as iron ore, all of it underwritten by the Chinese that all goes away, which means that Brazil will have to absolutely invent itself again.

That’s going to be, at best, a 30 year process. And in the meantime, the social breakdown and the economic breakdown that is going to plague the country is going to be immense, meaning that there aren’t going to be a lot of places in Brazil that are really worth going to. But the Copacabana, right on the beach is kind of the quintessential expression of Brazilian economic inequality.

You basically have these really, really rich pockets that will still be beautiful and they’ll be surrounded by slums. For those of you who have been to Brazil before, you notice that that is not exactly a new concept, but it’s going to become much more concentrated and the disparities will be much more obvious.