Based on our discussion yesterday, we’re looking back at this post from April of last year to see how things have evolved.

It looks like the Europeans may have figured out that Russia’s war plans don’t end in Ukraine, so more and more countries are beginning to send aid to the Ukrainians. The Americans, however, are still working through flawed economics and political considerations.

The Norwegian government has decided to send some F-16s to Ukraine, joining Denmark, the Netherlands, and others in providing military support. The most important shift we’re seeing in aid sent to Ukraine is that it is intended to be used on Russian infrastructure and military units…within the Russian border.

The Biden administration’s caution regarding Ukrainian targeting is based on flawed economic analysis and pointless political considerations. This has led us to a strange intersection of this war, where Europe is done limiting Ukraine’s actions in fighting, but the more commonly aggressive American stance is still lagging behind.

TranscripT

Hey, everybody. Peter Zeihan here, coming to you from a very windy Colorado. It is the 16th of April, and the news today is that the Norwegian government has announced that they are joining the coalition of growing countries that is setting F-16 jets to Ukraine, specifically the foreign minister, a guy by the name of Aspen Barth, I’d, probably has said specifically he hopes and encourages the Ukrainians to use the jets that at the moment are being provided by a coalition of Norway, Denmark and the Netherlands, to stark to target infrastructure and military units actually in Russia proper.

In fact, his phrase was the deeper the better lot going on here to impact. So number one, to this point, the NATO countries have tried to limit the direct attacks by the Ukrainians with their equipment or with equipment that is donated, in order to prevent an escalation. But a few people’s minds have been tripped in recent days because the Ukrainians are now using one and two tonne bombs to completely obliterate civilian infrastructure and are going after aid workers, including, things like E-m-s services.

And this is really tripped the minds of a lot of people in northern Europe in particular, that this war is now gotten way too serious to have any sort of guardrails on what the Ukrainians can target. The French. Well, they have not weighed in on this topic specifically. They’re now openly discussing when, not whether when French troops are going to be deployed to Ukraine to assist the Ukrainians in a rearguard action.

And we have a number of other countries, especially in the Baltics and in Central Europe, that are also wanting to amp up the European commitment to the war. In part, this is just the recognition that if Ukraine falls, they’re all next, and in part is that the United States has abdicated a degree of leadership, both because of targeting restrictions and because there’s a faction within the House of Representatives that is preventing aid from flowing to Ukraine.

So the Europeans are stepping up. In fact, they’ve been stepping up now for nine months. They provided more military and financial aid to the Ukrainians each and every month for nine months now. And this is just kind of the next logical step in that process, which puts the United States in this weird position of being the large country that is arguing the most vociferously for a dialing back of targeting, by Ukraine, of Russian assets in Russia.

If you guys remember, back about three weeks ago, there was a report from the Financial Times that the Biden administration had alerted the Ukrainians that they did not want the Ukrainians to target, for example, oil refineries in Russia because of the impact that could have on global energy prices. And I refrained from commenting at that time because it wasn’t clear to me from how far up the chain it has come.

That warning. But in the last week we have heard national Security adviser Jake Sullivan and the vice president, Kamala Harris, both specifically on and on record, warn the Ukrainians that the United States did not want them targeting this sort of infrastructure because of the impact it would have on policy, and on inflation. Now that we know it’s coming from the White House itself, I feel kind of released to comment.

And I don’t really have a very positive comment here. There’s two things going on. Number one, it’s based on some really, really faulty logic and some bad economic analysis. So step one is the concern in the United States that higher energy prices are going to restrict the ability of the Europeans to rally to the cause and support Ukraine.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Most of the Europeans realize that if Ukraine falls they’re next and most of the countries with an activist foreign policy are already firmly on the side of an expanded targeting regime. The biggest holdout would be Germany, where we have an unstable and unconfident leader and coalition that wants to lead from the back, not the front, which I can understand, but most of the Europeans have realized that if we’re actually getting ready for an actual war between Europe and Russia, that’s not going to be free.

And higher energy costs are just kind of baked into that pie. So almost all of the Europeans have basically cut almost all Russian energy out of their fuel mixes already in anticipation for that fight. So argument number one, gone. number two, the idea that this is going to cause the war to expand in a way that will damage Ukraine more.

Well, one of the first things that the Russians did back in 2022, in the war, was target all Ukrainian oil processing facilities. They don’t have much left. So, yes, there’s more things that the Russians can do, but this is basically turned into a semi genocidal war. So it’s really hard to restrain the Ukrainians and doing things that are going to hurt the Russian bottom line that allows them to fund the war.

So that kind of falls apart. specifically, the Ukrainians have proven with home grown weaponry they don’t even need Western weapons for this. They can do precision attacks on Russian refineries, going after some of the really sensitive bits. Now, refineries are huge facilities with a lot of internal distance and a lot of standoff distance. So if you have an explosion in one section, it doesn’t make the whole thing go up like it might in Hollywood.

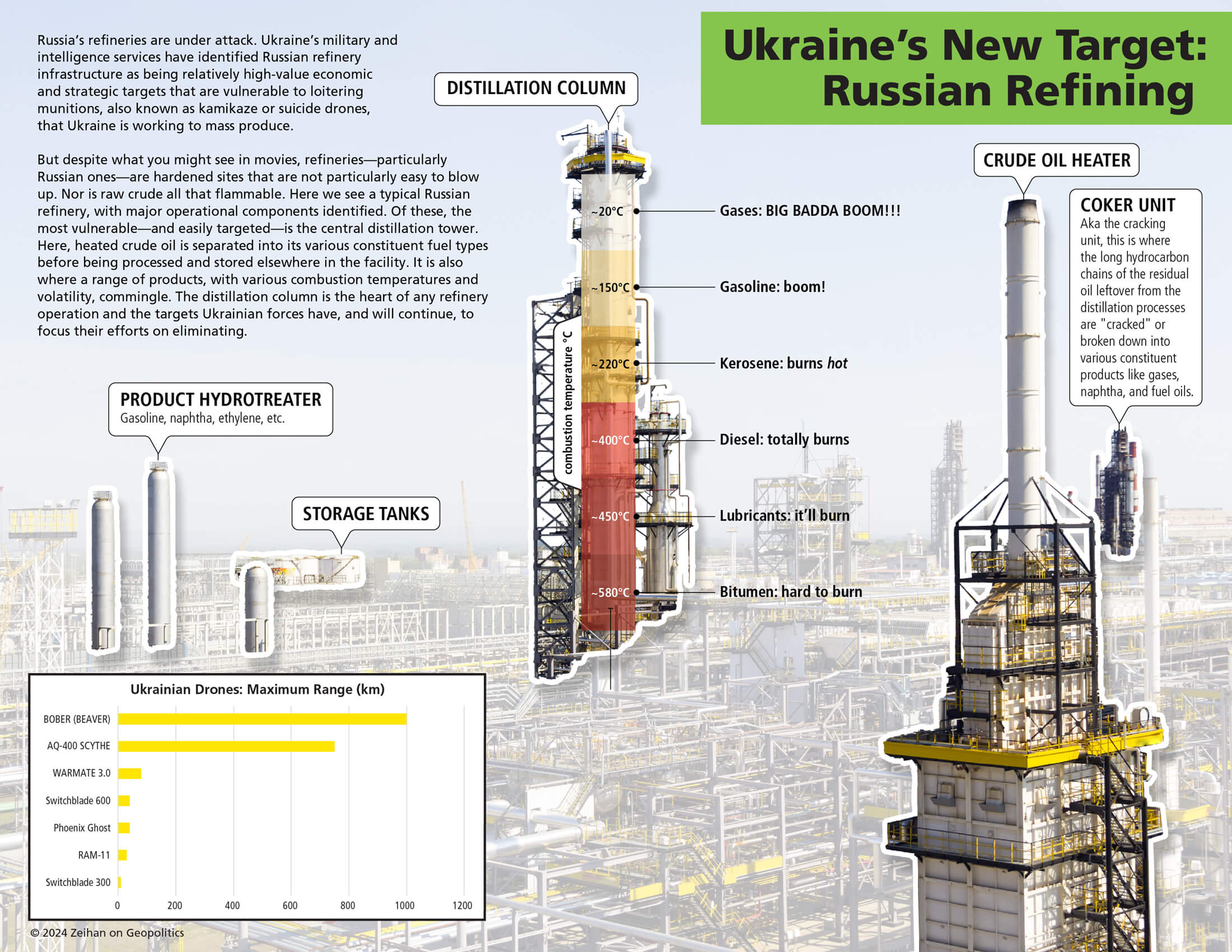

As a result, there are very specific places that you have to hit, and that requires a degree of precision and accuracy that most countries can’t demonstrate. But the Ukrainians have a specifically go after something called a distillation tower, which is where you basically take heated crude and you put into a giant fractionated column, if you remember high school chemistry, and if you can poke a hole in that, it’s hot and it’s pressurized.

So you get something that spurts out and based where on the verticality you hit. The products that hit are either flammable or explosive. So we’re including a nice little graphic here to show you what that looks like. the Ukrainians have shown that they can hit this in a dozen different facilities, and the Russians have proven that it’s difficult for them to get this stuff back online, because most of the equipment, especially for his distillation tower, is not produced in Russia.

And a lot of it’s not even produced in China. It’s mostly Western tech. So as of April 2nd, which was the last day we had an attack on energy infrastructure in Russia, about 15% of Russian refining capacity had been taken offline. In the two weeks since then, they’ve gotten about a third of that back on using parts they were able to cobble together.

But it gives you an idea that this is a real drain, because we’re talking about 600,000 barrels a day of refined product that just isn’t being made right now. That affects domestic stability in Russia, that affects the capacity of the Russians to operate in the front. And yes, it does impact global energy prices, but that leads me to the third thing that I have a problem with the Biden administration here, and that the impact on the United States is pretty limited.

the United States is not simply the world’s largest producer of crude oil. It’s also the world’s largest producer of refined product to the degree that it is also the world’s largest exporter of refined product. So not only will the United States feel the least pinch in terms of energy inflation from anything in Russia going offline, we also have the issue that the US president, without having to go through Congress, can put restrictions of whatever form he wants on United States export of product.

Doesn’t require a lot of regulatory creativity to come up with a plan that would allow to a limiting of the impact to prices, for energy products in the United States. And I got to say, it is weird to see the United States playing the role of dove when it comes to NATO issues with Ukraine. Usually the U.S. is the hawk.

Now, I don’t think this is going to last. the Biden administration’s logic and analysis on this is just flat out wrong. geopolitically, there’s already a coalition of European countries that wants to take the fight across the border into Russia proper, because they know that now, that’s really the only way that the Ukrainians can win this war.

Second, economically, you take let’s say you take half of Russia’s refined product exports offline. Will that have an impact? Yeah, but it will be relatively moderate because most countries have been moving away from that already. And the Russian product is going to over halfway around the world before it makes it to an end client. So it’s already been stretched.

Removing it will have an impact. But we’ve had two years to adapt, so it’s going to be moderate, though not to mention in the United States, as the world’s largest refined product exporter, we’re already in a glut here, and it doesn’t take much bureaucratic minutia in order to keep some of that glut from going abroad. So mitigating any price impact here for political reasons.

And third, the political context is wrong to the Biden administration is thinking about inflation and how that can be a voter issue, and it is a voter issue. But if you keep the gasoline and the refined product bottle up in the United States, the only people are going to be pissed off are the refiners. And I don’t think any of those people are going to ever vote for the Biden administration in the first place.

There is no need to restrict Ukrainians room to maneuver in order to fight this war. in order to get everything that the Biden administration says that it wants to be.