If I was tasked with raising and educating the next generation of workers (aka what middle school teachers do daily), what would I teach my minions (okay fine, “students”) to best prepare them for the future?

In the School of Zeihan, there will be 2 major areas of focus: Spanish and skilled trades. That’s right, instead of pencil cases and books, I’ll be handing out tool belts and Rosetta Stones on the first day of class.

Spanish will be essential, as Mexico will be one of our most dominant trade partners for the next 50+ years. Extra credit for the kids that can pick up some technical Spanish to bridge the gap in bilingual technical expertise – you know, to manage the semiconductor, automotive and aerospace industries.

After their Spanish lessons, the kids will head over to shop class. We’ll be churning out electricians, construction workers, and just about every other blue-collar position to ensure we can cover the demand associated with doubling the industrial capacity in the US.

So, who wants to enroll their kids in the Colegio Zeihan?

Here at Zeihan on Geopolitics, our chosen charity partner is MedShare. They provide emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it, so we can be sure that every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence.

For those who would like to donate directly to MedShare or to learn more about their efforts, you can click this link.

Transcript

Hey, all Peter Zeihan here coming to you from an incredibly chilly Colorado. And today we’re to take a question from the Patreon page. Is like I’m a middle school teacher. What should I be teaching my kids to prepare for the future? Oh, I like this question. It’s a happy question. Okay. Number one Spanish. It’s the number two language in the United States.

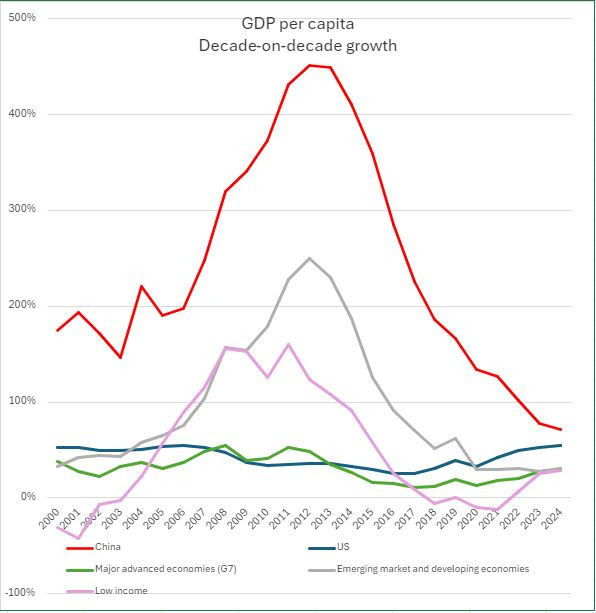

It’s the number one language. And our top trading partner and the demographics of Mexico, which are significantly younger than the United States, suggests that Mexico is going to be our top trading partner and pretty much every economic sector for at least the next 50 years. Any good beyond that and technology might change, but at least for the next 50 years, integration with Mexico is the story, especially as the Chinese fail.

Second, if you want to take the next logical step in that not just Spanish, but technical Spanish, the issue is that there are lots and lots of Americans who speak Spanish, and there are lots and lots of Mexicans who speak English, but there are not a lot of people on both sides who speak the technical aspects of specific parts of the language.

So, for example, 80% of the world’s low quality semiconductors, that’s 90 nanometers and dumber. Think of the Internet of Things, your smart refrigerator, that sort of thing. 90, 80% of those come out of mainland China. And when the Chinese system breaks, we’re going to have to do one of two things. We’re going to have to basically get by without the quality of chips.

And they’re in everything. So we basically digitize large sections of the economy, or we take this legacy technology, which in many cases is 20, even 30 years old, and we rebuild it somewhere else. And in the case of the United States, it’s probably not very cost effective. We’re probably going to be focusing on the middle and the higher end components that go into things like automotive and aerospace and power management, not to mention AI and satellites and cell phones and computers.

But Mexico is rapidly, especially in northern Mexico, is rapidly moving up the value added scale in every type of manufacturing they do. And they could probably, with a little bit of help, move into low end semiconductors with just a couple of years of effort. The problem is going to be the transition period between now and then. And for that, you’re going to need a lot of people in a technical capacity in these Mexican semiconductor fabrication facilities who can basically handle the language of the technical side of the manufacturing process, and that requires some very specific language skills that just don’t exist in the bilateral relationship right now.

And you can do the same thing as Mexico. It’s more sophisticated IT and aerospace and automotive and, wiring harnesses and basically everything that puts together a modern industry. Remember that as the Chinese system goes, that’s the workshop of the World Breaks. There’s going to be a lot of stuff that has to be relocated very, very quickly. And the sooner we can start on that, the better.

And this is probably, I would argue, more of a restriction on our ability to bring Mexico up to snuff quickly than anything having to do with capital or labor, which is saying something because those are huge problems. And then the third item is much more straightforward here in the United States, in Canada and Mexico, we basically need to double the size of the industrial plant, to replace what currently comes in from China.

Well, that’s a lot of construction workers. That’s a lot of bricklayers. That’s a lot of electricians. We need skilled blue collar labor with probably electricity manipulation, being the single largest gap in the workforce. So the two biggest things that you can do, if your goal is to earn a six figure salary right out of school, technical Spanish to become an electrician, language skills and shop class are looking really good right now.

And on top of that, the politics of this are pretty good too. We’re going to double the size of the industrial plant. Pretty much all of those jobs are going to be blue collar. So we do stand at the dawn of the golden age of organized labor. And if you can be the skilled labor within the organized labor who you can punch your own ticket however you want.

All right, that’s it.