Massive population shocks are nothing new; just look at the Mongol invasions or the Black Death. But is the demographic collapse of today comparable to those historic cases? Or are we staring down the barrel of something entirely new?

Well, we’re not going to get a step-by-step guide by looking back at the Mongol invasions and Black Death, but there is a lesson in there. The collapse happens fast (relatively speaking). The building back and transitional times…that happens over generations.

So, demographic collapse isn’t the end; it’s the start of a long and painful process of finding a new system that works. Japan, China, Germany, and Russia will do a bit of guinea pigging for the rest of the world, but everyone’s heading there eventually.

Transcript

Hey, all, happy autumn from Colorado. Peter Zeihan here. Today we are taking a question from the Patreon crowd specifically. Could I take a look at the demographic decline that’s going on today and compare it to past periods where there’s been population collapses, specifically, the Mongol invasion of the 1200s and the Black Death of the 1300s. Okay.

Great idea. I’m not sure we’re gonna be able to draw too many comparisons here, but I’ll give you my thinking. Which shapes why I’m very circumspect when it comes to specific forecasts based on demographics. The situation we’re in today is because of industrialization. We all started to urbanize, which means we all started to have fewer kids because on the farm, kids are free labor in the city.

They’re just an expense. And people can do math, which means that over the course of the next ten year period before 2035, about half of the developed world, plus China is basically going to age into an environment where our economics models don’t work anymore, and they’re all looking at some sort of national, civic or economic collapse going to be pretty ugly beyond that.

So let’s start with the Mongols. Among us were some scary dudes. And when they started rampaging across Asia and getting to the eastern rim of Europe, they had such a reputation that people ran before them literally until they could get to what is today Poland, because in Poland there were forests. And when the Mongols would charge into the forest, they couldn’t really operate as horsemen.

They had to dismount. And then all of a sudden they were numbered 100 to 1. So Poland was kind of where the line was. And then, we had a government change among the Mongols. It was a clan based structure. And when Big Papa died, all the little boys went back to Mongolia and basically had an argument over who was going to be the next big papa. And that triggered, civil unrest and basically led to the end of the Mongol Empire.

Later, a few decades, a new government rose on the scene called the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Basically, Poland and Lithuania, had some neighbors, the Latvians, the Germans, whatever. And when they went into those lands, they discovered that there was resistance.

But if they went east, the lands were almost completely empty. So they started going east, and then they found one another and they had a little spat as expanding empires do. They cut a deal. They formed the Commonwealth, and over the next century they became the largest, most sophisticated political and economic structure that Europe had known to that point.

So clearing the decks demographically can generate something new and maybe even something wonderful if you can get through the transition. The second example is, if anything, even more poignant. That’s the Black Death. When rats carried by traitors spread bubonic plague. Went throughout all of Europe.

And based on where you were, either one third of your population died, if you were lucky or maybe even over half, that generated a different sort of transformation. largely because of population dynamics. Even after the Black Plague swept through western and southern Europe, these areas had higher population densities than the lands east of Poland did before the Mongols arrived. So these places suffered hugely. But they weren’t emptied out and what they discovered is to maintain the bones of civilization, much less build something new.

Nobody had enough skilled labor to handle the metal of the wood or whatever it happened to be. So from the Colonel, survivors of skilled labor, we saw an explosion in training, as everyone had to figure out how to do more with less. That’s another word for technology. And so we triggered the Renaissance, which led in time to the Age of Discovery and ultimately the industrial age.

So both of these examples are great for showing how demographic collapse isn’t the end. But you have to keep a few things in mind. Number one, it takes some time in the case of, the Mongol invasion, for example, it was roughly 1240, 1242, I think, when the Mongols went home and never came back. Poland, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth wasn’t finalized until like 150 years later.

So, you know, you’re talking 3 to 5 generations of time where you basically had a lot of empty, the area would have been called something like marches. In the case of the Renaissance and the Black Plague, it was faster because the population wasn’t wiped out, but still, Black Plague hit about 1350. It wasn’t until 1400 that the Renaissance got going, and the Age of Discovery started 50 to 100 years after that.

But for that to shape the general political environment took a lot longer. During this time, during the dark Ages, which was, you know, at this point, almost 800 years in, it was a horrible system, but it was stable. The most powerful country in the world was Ottoman Turkey, because they had a defensible core in the Sea of Marmara region, and they had access to multiple maritime routes of expansion, the Levant, the Aegean Sea into the Mediterranean, the Black Sea and especially the Danube.

And they would basically expand down those maritime routes. When the Age of Discovery clashed with the Ottomans, the first time it happenedwas in 1529. You know, it’s a couple centuries after the Black Plague and it was indeterminate.

In the meantime, you had the Age of Discovery continuing with the Portuguese and eventually the Spanish, discovering the new world, stitching together new routes, the old world technology generally progressing, and it would in time overpower the Ottomans.

But the high water point for the Ottomans didn’t happen until the late 1600s. And it was another century after that, until you got the revolutions of 1787 that actually broke Ottoman power. And even then, the Ottoman Empire lasted for another 40 years before ultimately dying in World War one takes a lot of time for stable systems to unspool.

So when you’re using these lessons and looking at our near future, yes, the demographic transition from our point of view is going to be very fast the next ten years, or it’s going to be lightning fast and the collapse of individual systems, we’re going to feel in our bones, but waiting for something that is stable to replace it on the other side.

That requires inventing new models. Ever since the Age of Discovery, we’ve become inured to this idea that the patterns are permanent for every year except for 1 or 2 of the last 500, the human population has gotten bigger. And because of that, economic models that favor expansion do really well. That’s socialism, capitalism, fascism and communism. But if the population starts to shrink, those models aren’t going to make sense anymore.

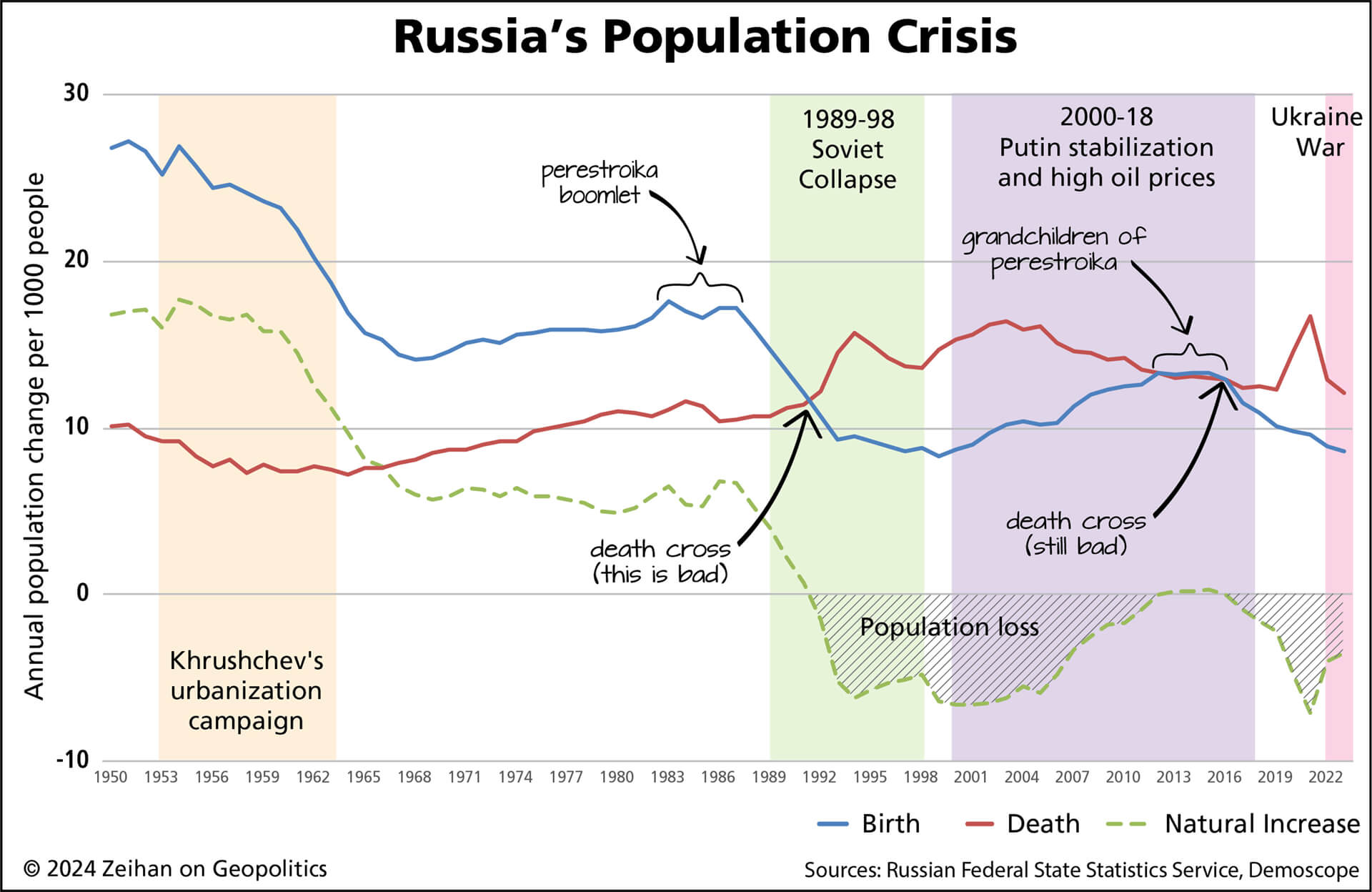

And we’re gonna have to invent something new. And the places that have to deal with that first are the ones where the demographic decline is going to come first and be fastest, and the countries on my list for that, that really matter are Japan, China, Germany and Russia, in no particular order. And if you know anything about the histories of those four countries, when they get insecure, things get a little exciting.

So I can guarantee you that things are going to change. I can guarantee you that the models which we run our economic systems by are going to be different. What I can’t tell you is when this is going to settle out, because I’m probably not going to be around anymore at that point.