Part I of this newsletter published a week ago, before we had enough U.S. states reporting election results to call the race. Now, barring something truly odd, Joe Biden has won a more than sufficient number of states to be considered President-elect.

For those who follow my work, it should come as no surprise that I’m not a big fan of either sitting president Donald Trump or the new President-elect. I’m a foreign policy guy and neither man has shown the interest in or competence to build something that will outlast him.

This isn’t entirely their fault. The United States is the least involved economy in the global system as measured as a percent of GDP, with the single biggest chunk of that involvement wrapped up with America’s neighboring NAFTA partners. My preferences aside, there is no burning need in the United States for global engagement. No wonder that aside from issues relating to the September 11, 2001 attacks and the Iraq War, Americans haven’t considered foreign policy an above-the-fold issue for the bulk of the post-Cold War era.

But this new norm will not last forever. Americans will care about the world again someday. The question is what does the road from here to there look like?

There are two ways the Americans might reengage in the future.

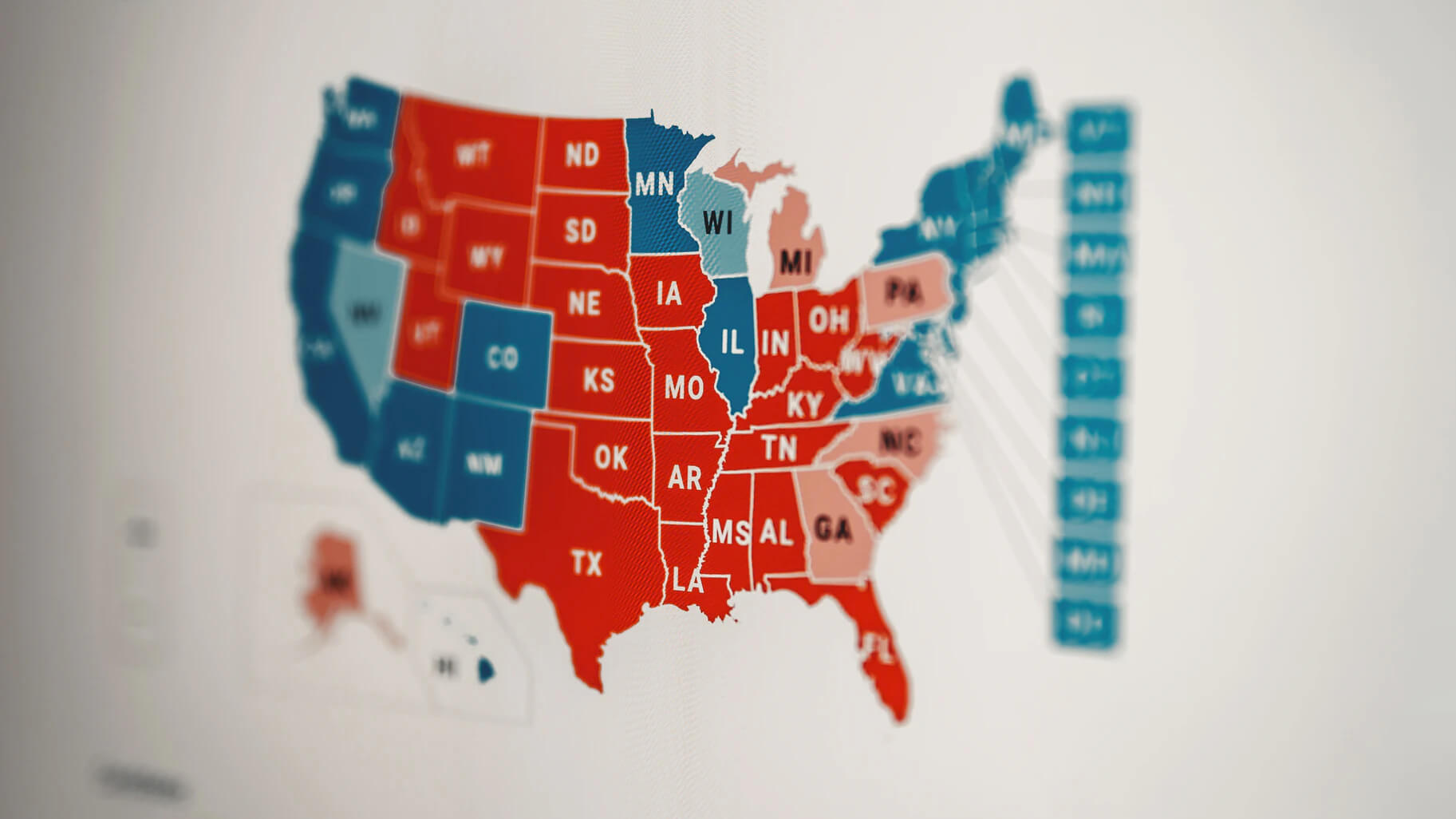

The first is the internal route. The (always fractious) American political system is, at present, in a state of breakdown. American first-past-the post electoral laws – the winner for each seat need only gain one more vote than whoever comes in second place – forces a two-party system. That induces the parties to behave certain ways. If they focus too much on explicit policies, they tend to alienate large swathes of the electorate. Instead they throw wide nets to include as many different factions as possible: evangelicals, business owners, pro-lifers, national security enthusiasts and fiscal obsessives for the Republicans; pro-choicers, environmentalists, socialists, organized labor, the youth and a rainbow of minorities for the Democrats.

But there is nothing hard-and-fast or permanent about these coalitions. As culture and technology and the economy and the world evolve, so too do the factions. Today the factions are shifting furiously. Union voters have all but become Trumpist Republicans (the AFL-CIO chief was in the Oval Office endorsing Trump’s NAFTA renegotiation while the rest of the Democratic coalition was hanging with Nancy Pelosi putting the finishing touches on Trump’s impeachment). National security voters are sniffing about the Democrats (every politically active living former intelligence chief and Secretary of State and Secretary of Defense endorsed Biden rather than Trump). Businesspeople – equally appalled by Trump’s erraticism and Biden’s tax plans – are in the wind.

Such reshuffling is normal. Healthy even. Political coalitions reflect strategic, cultural and economic realities, and over time those realities evolve. No political coalition is forever. No party is forever. The War of 1812 did in the Federalists. Westward expansion birthed the Democrats. The Whigs withered away as America geared up for its Civil War. The trauma of the Great Depression saw Black Americans abandon the Republicans for the Democrats while business leaders went the opposite direction. Today’s reshuffling – a reaction to the Cold War’s end and the Digital Revolution – is America’s seventh.

The Americans cannot even begin a conversation with one another about what they want out of the world until they’ve sorted out their internal political evolution. Only then can they begin to craft a grand strategy, and only then can they begin to assemble and implement a meaningful foreign policy. But the reordering takes time. The last party restructuring in the 1930s and 1940s took twelve years. This time around the Americans are only in year five. That means the global superpower is out to lunch until a point far closer to 2030 than 2020. What engagement occurs has been reduced to little more than presidential whim.

The second route is externally driven, and far, far more dangerous: Something pops up that scares the Americans, forcing them back into the world.

This was the strategy of Osama Bin Laden: attack the Americans in a way they could not ignore to induce them to slam sideways into the Middle East. OBL’s thinking was the Americans would partner with the region’s secular leaders to hunt down al Qaeda, and that partnership would so enrage the ummah that the Islamic masses would rise up and overthrow their rulers, ushering in a new Muslim Empire.

It obviously didn’t work out the way he had hoped. Yes, the Americans became embroiled in a pair of decades-long wars, and yes, those wars contributed to the Arab Spring and Arab Winter which in turn shattered the regional order, and yes, those wars and that shattering pushed a half dozen countries – so far – into de facto collapse.

But a pan-Islamist empire? The region is further from that now than ever. Of more lasting significance, by 2020 the Americans have largely abandoned the region to its own devices. America now boasts a military that is not only rested, recuperated and rearmed, but battle-hardened.

Any new American lash-out would undoubtedly be more violent and holistic than their recently ended Middle Eastern adventures. In part it is the inexorable march of military technology: America’s stealth bombers can now strike any position on Earth from their home bases in Missouri, while American drones can dominate a battlefield without need of a single solider in theater. Americans may be gun-shy about invading and occupying other countries at present, but such weapons systems make them eminently willing and able to devastate anything, anywhere, at any time. After declaring victory, the Americans don’t even need to go home because they will have never left in the first place.

But the bigger piece of the picture is economic. In the two decades since the September 11, 2001 attacks, the United States has become economically divorced from the wider world. The shale revolution has severed the thickest, most strategically significant link between the American economy and global norms. Integration with Mexico has reduced American dependence upon global manufactures. The entire American political spectrum now firmly anti-China, Americans are ready and willing – even eager – to cut the remainder of the ties that bind.

In the 2000s the Americans were always cautious about where and how they acted in an economic sense. For example, they knew Saudi elements played leading roles in the 9/11 attacks, yet the Americans largely spared Saudi interests for fear of repercussions in the oil market. If provoked today, the Americans truly would not care about what the world would look like the morning after any retaliatory actions, because they are now largely immune to any collateral damage.

Consider America’s post-Cold War conflicts: Somalia, Bosnia, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq. Sure, none of the places turned out to quite be Wisconsin, but imagine for the moment if the Americans had treated them all like Yemen: liberally applying ammunition to strategic bombing and assassination efforts and never sparing a thought to occupation or reconstruction. Simply wreck all economic and political infrastructure and then … leave.

This is the new normal for American policy. Any country stupid enough to provoke the Americans now will get something far harsher than the fate which ultimately befell OBL.

Massive capacity. No concern for credibility. No hint of a goal. No care for the aftermath. It’s a volatile, dangerous mix. And until the Americans can find a new internal balance, it’s the world we all live in.

If you enjoy our free newsletters, the team at Zeihan on Geopolitics asks you to consider donating to Feeding America.

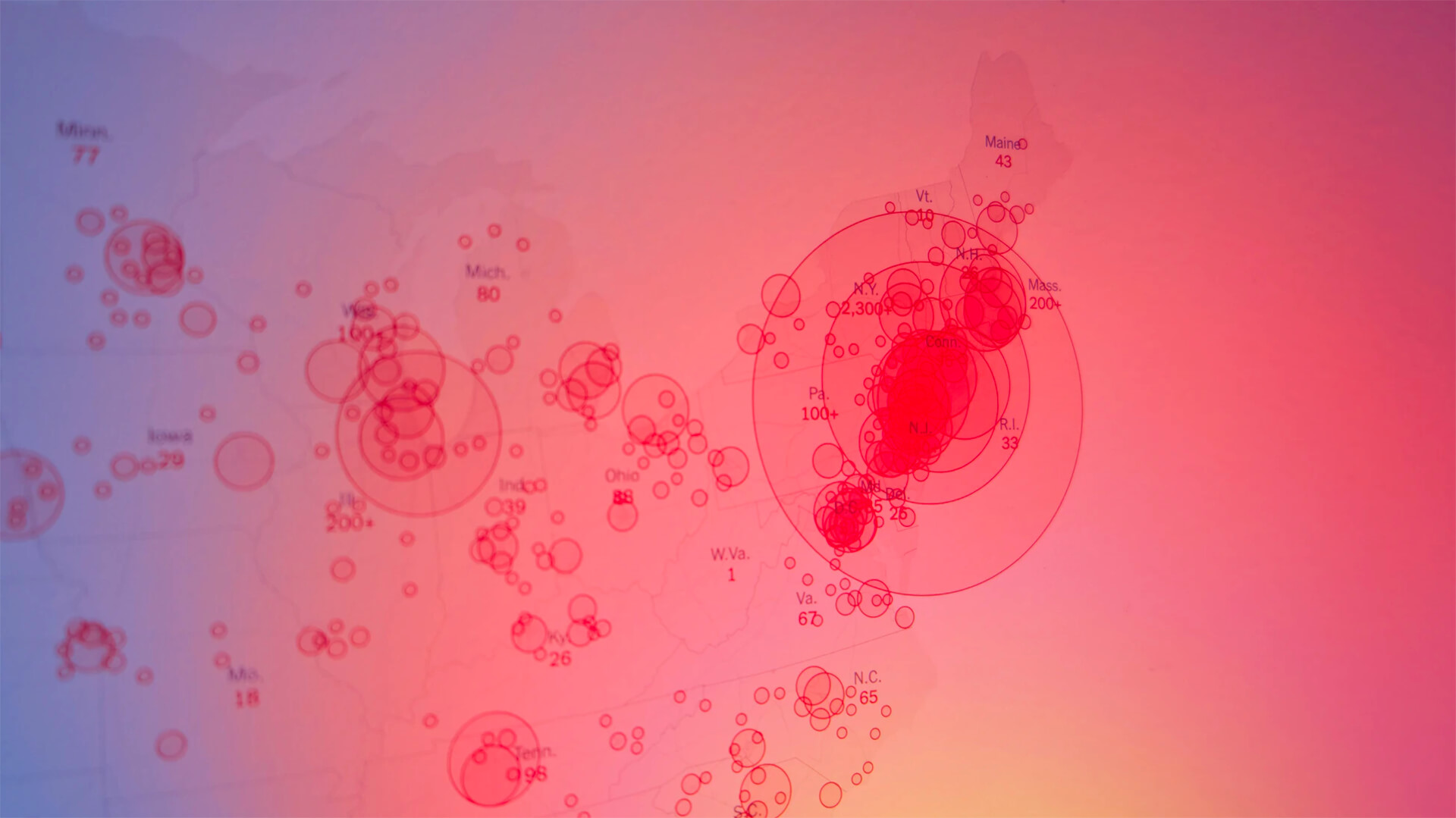

The economic lockdowns in the wake of COVID-19 left many without jobs and additional tens of millions of people, including children, without reliable food. Feeding America works with food manufacturers and suppliers to provide meals for those in need and provides direct support to America’s food banks.

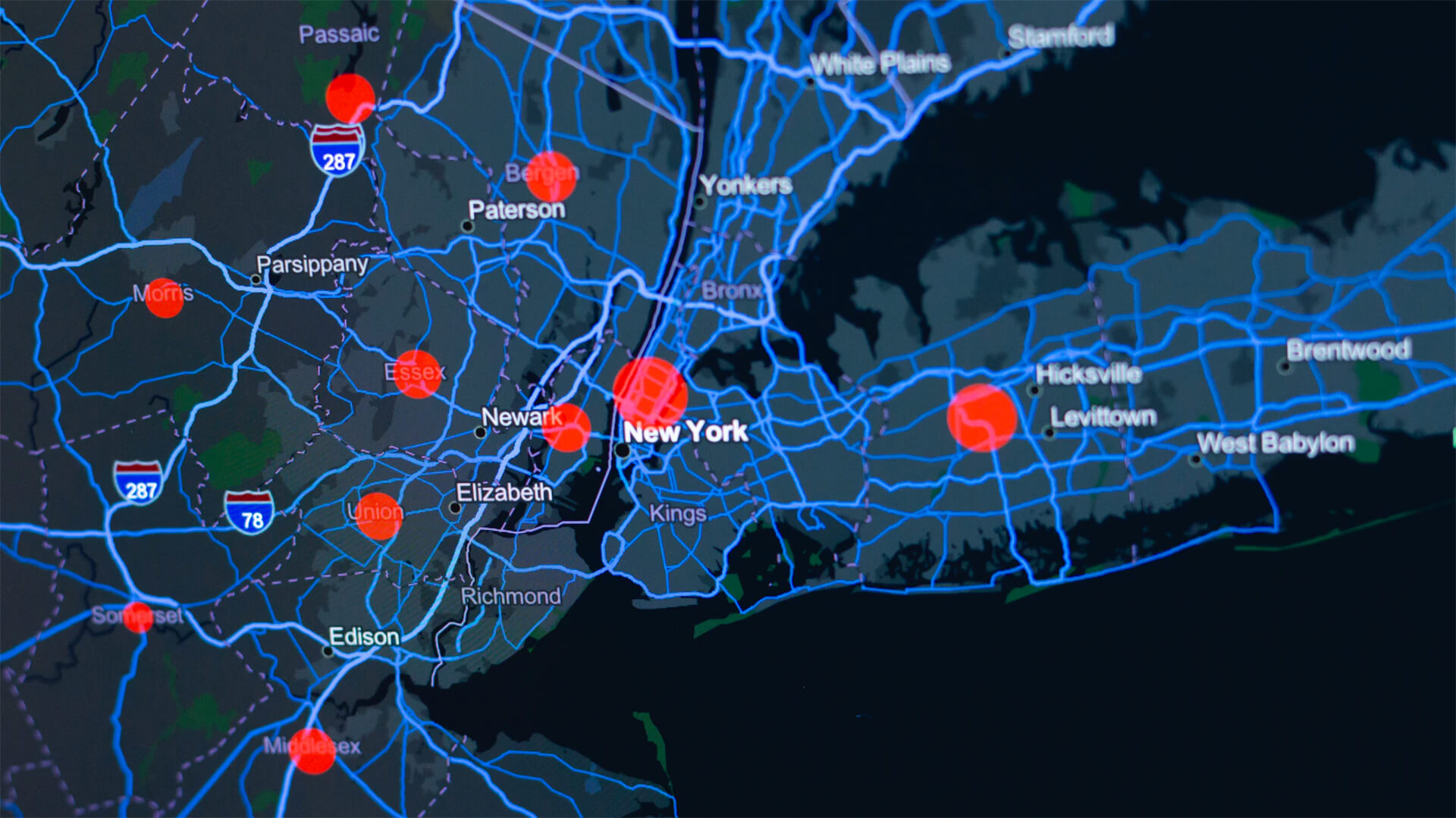

Food pantries are facing declining donations from grocery stores with stretched supply chains. At the same time, they are doing what they can to quickly scale their operations to meet demand. But they need donations – they need cash – to do so now.

Feeding America is a great way to help in difficult times.

The team at Zeihan on Geopolitics thanks you and hopes you continue to enjoy our work.

DONATE TO FEEDING AMERICA