In President Biden’s State of the Union address a few days ago, he announced plans to build a floating dock to deliver humanitarian aid to Gaza. This dock would help provide significant food supplies to this area, but at what cost?

You can probably imagine how the Israelis feel about this floating dock, but is that really the worst thing? This move by the US will carry significant diplomatic and strategic repercussions, but a shift away from Israel and some other Middle Eastern powers might be exactly what President Biden is going for.

With the potential for a reshuffling of Middle Eastern alliances and relationships, the opportunity to buddy up with a much more powerful country – like ahem, Turkey – is on the table. There’s no telling how all of this will shake out, but its likely that US policy in the Middle East is shifting.

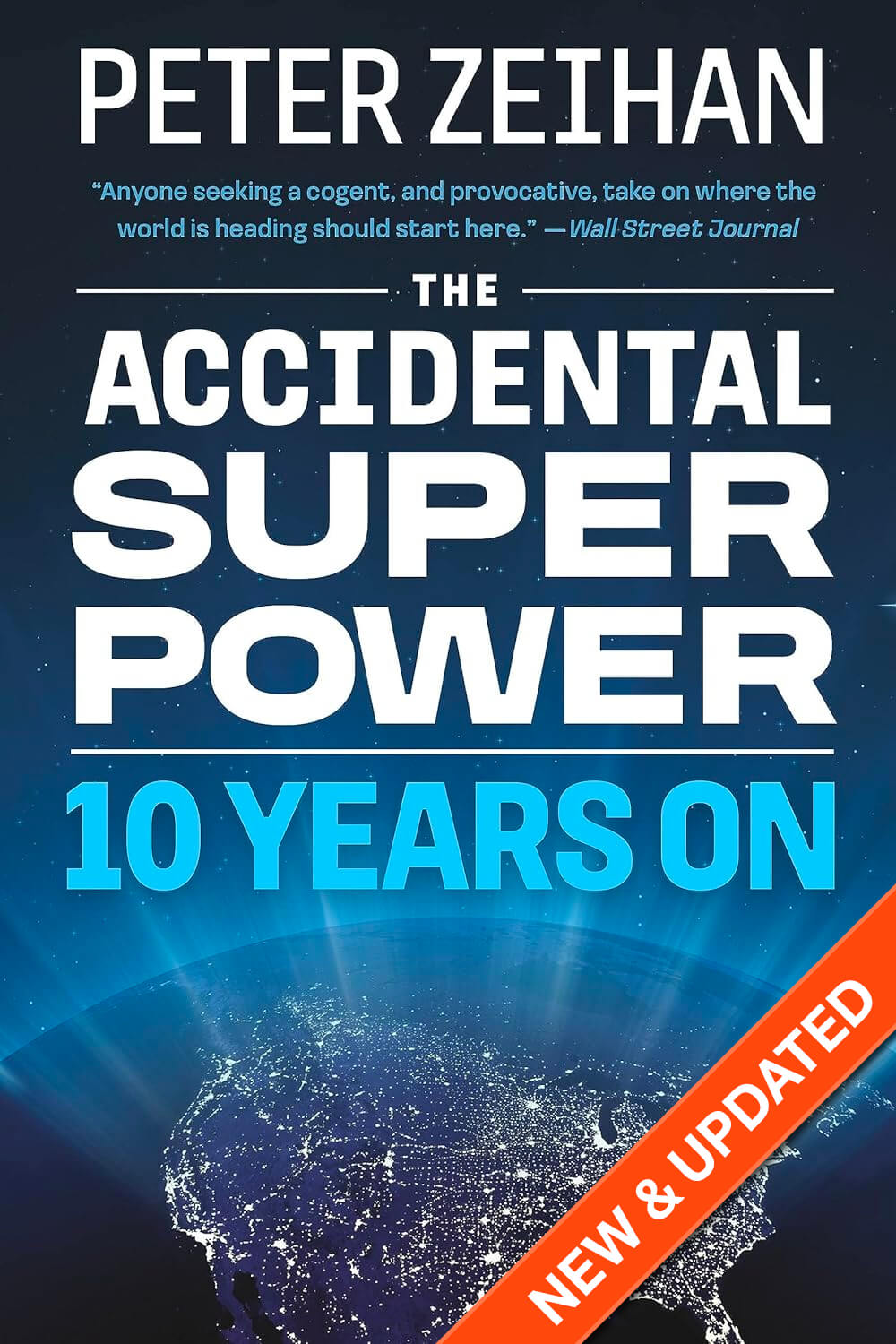

Here at Zeihan On Geopolitics we select a single charity to sponsor. We have two criteria:

First, we look across the world and use our skill sets to identify where the needs are most acute. Second, we look for an institution with preexisting networks for both materials gathering and aid distribution. That way we know every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence. Then we give what we can.

Today, our chosen charity is a group called Medshare, which provides emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it. Until future notice, every cent we earn from every book we sell in every format through every retailer is going to Medshare’s Ukraine fund.

And then there’s you.

Our newsletters and videologues are not only free, they will always be free. We also will never share your contact information with anyone. All we ask is that if you find one of our releases in any way useful, that you make a donation to Medshare. Over one third of Ukraine’s pre-war population has either been forced from their homes, kidnapped and shipped to Russia, or is trying to survive in occupied lands. This is our way to help who we can. Please, join us.

TranscripT

Hey everybody. Peter Zeihan here coming to you from Colorado. Have kind of a weird one for you today because I’m not sure if I’m really no idea where it’s going, but this event has the potential for remaking a lot of things with U.S. policy in the Middle East in general. If you guys watched the State of the Union address a couple of days ago, almost a throwaway line that people like blurbed about for 5 minutes and then immediately forgot.

Was the Biden administration is committed publicly to building a floating dock that services the Gaza territory in order to get humanitarian aid in. The idea is that the throughput will be enough for at least 2 million meals a day, which would be roughly one third of the food demands for the territory. Now, remember, Gaza is basically a walled, open air prison camp, and so they grow no food themselves.

They’re completely dependent upon aid. And in the aftermath of the October Hamas attacks on Israel that killed some 1600 people, just horrific attack. The Israeli counter effort to try to root out Hamas has destroyed probably two thirds of the housing stock within Gaza. Probably more than that of their infrastructure. And they’re gearing up for another assault in the southern part of the strip to go after what they think are the remnants of Hamas, which is where now most of the population has been huddled because the rest of the strip has been destroyed.

Already, we’ve seen about 35,000 deaths among the Gaza population, which is over 1% of the pre-war civilian population. And if the Rafah attack happens over at least half of that number of casualties again. So this has already become the single most high casualty conflict in recent years that is not in sub-Saharan Africa. And it’s only going to get worse before it gets better.

And there is no version of a future where Gaza is self-sustaining. They don’t generate their own energy. They can’t grow their own food. Everything comes in from aid from somewhere else. And because of the war, the Israelis have basically blockaded the entrances, except for some very, very specific circumstances. Anyway. The Biden administration let me rephrase that. Biden personally, when he was vice president, if you remember, Obama hated everybody, didn’t want to have conversations with anyone.

And so he basically sent Biden to do all the talking, especially in the Middle East, because there was a region. Obama wasn’t interested in anything, but he was really not interested in the Middle East. So Biden has a first name, a relationship with most of the leaders across the region, and he and the Israelis did not get along at all, especially Netanyahu.

And I mean, let’s be perfectly blunt here in Kenya, who is an asshole and no one likes him, but he’s an effective political leader when it comes to managing a coalition. And his attitude hasn’t changed at all during the conflict. If anything, it’s hardened. And so he’s basically ignored what everyone has said about the conflict pursuing Israeli national interests.

I don’t mean that in a bad way. There is no way that Israel will be secure so long as Hamas exists. And I don’t see a way to destroy Hamas without destroying Gaza. But between that immovable rock and that irresistible force, the United States is attempting to find a third way. It won’t work, but it’s attempting to find a way to allow the Palestinians to at least live from.

So you have to have a degree of respect for at least that. Here’s the thing. There is no version of what the Biden administration has now pledged itself to do that meshes with any version of Israeli national security, regardless of who is in charge in Jerusalem. Even if the left wing peaceniks took over in Israel, tomorrow, they would still be opposed to this.

This this cuts to the core of Israeli survivability. And there is broad support for the military operation in Gaza across the political spectrum despite the civilian casualties. So there is no way there’s no way that the Biden administration is unaware of this and there is no way that the Joint Chiefs didn’t explain to the cabinet of the Biden administration that if we do this, we then also have to bring in a logistics team in order to deliver aid by small boat to this dock.

And then we have to put boots on the ground in Gaza to set up a truck distribution system to get the aid to the people. Remember, 2 million meals a day. This is on a much larger scale than what went down with the Berlin airlift. And with the Berlin airlift. You could just drop it and fly away. Here you’re talking about having to deliver it.

The U.N. can’t operate in Gaza in war. Only the U.S. military could. So we’re now talking about having a larger U.S. military presence in and around Gaza than it has in the rest of the Middle East put together. There is no version of that that the Israelis are okay with. And it begs the question, what happens the next day?

So let me give you the caveat first. It’s a floating dock. The military could just leave. This isn’t like the Afghan evacuation in Afghanistan. The Kabul airport was an air bridge. Moving things by air is incredibly expensive and is a hell of a bottleneck. And you can only fit a few hundred people on each individual craft when you’re dealing with a naval operation.

This is the sort of thing the U.S. excels at. And if the decision was made to pull the plug, every U.S. military personnel could be out of there in a few hours. So we’re not setting up for a repeat of that. But we are setting up for a military footprint that is significant in a place that has absolutely no strategic value to the United States.

Also, Hamas is still very active in this region. Israel’s not done. So there will be attacks on U.S. forces. Biden knows this. Biden knows all of this. And so what happens the next day? It feels like the United States is preparing to breach the Israeli relationship. And if you do that, there are a number of secondary decisions that have to be made in a very short period of time.

Now, remember, the Biden administration is the administration that ended the American involvement in Afghanistan and has slimmed down our involvement everywhere else in the region to very, very thin bones. Going from here to a full pullout through the entire region. That is very possible. But think of the alliances that are forming up within this region right now. The Israelis have succeeded in building up diplomatic relationships, not just with Jordan and Egypt, but with Morocco and with Tunisia and with the UAE.

And they’re inches away from having a normalized relationship with Saudi Arabia. If the United States decides to cut and run from Israel, that means all of these countries are on their own. Now, there’s any number of ways that the U.S. can disengage. One of them is to induce other powers like the Arabs and the Israelis, to work together out of a sense of desperation.

This could do that. But that would also mean that the United States is preparing to cut its connection with the slave states of the Persian Gulf. That would be gutter the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, three countries that important vast quantities of labor abuse them horribly and then send them home when they’re no longer useful to them.

This would mean an end to that, too. Now, if if, if if this is the Biden administration’s plan and if if if the Biden administration wants to have influence in the region after this, it would have to make a partnership with another player. The only option is Turkey. And we have seen renewed diplomatic connections between the Biden administration and the other white administration of Turkey over the course of the last couple of months.

Now, the Turks in the current government don’t like the Israelis very much at all, but they by far the Turks have the most powerful military in the region, arguably more powerful than everyone else has put together. If there is to be a post Israel post Saudi American position in the region, it has to be with Turkey. And so there’s already been multiple meetings at the assistant defense secretary level to figure out how we can get along again, because those relations have been poor ever since the Iraq war started back in 2003.

So this has the potential to be game changing for the region. And as for someone who has kind of been sick of dealing with this region for the last 20 years, I got to admit it’s a kind of an attractive approach. The Israelis are carrying out a military operation that is making everybody squeamish, even countries that don’t much care for the Palestinians, and using this as a way to not just reduce relations with the Israelis who are apoplectic about this dog, but the Saudis and the Emiratis as well.

And to get along with a country that is much more democratic, which is much more strategically viable, that is much more capable. That’s a good trade. But there’s a lot of water that has to flow under this bridge as it’s being built before we get there. And we’re not going to have a good idea of just how committed the Biden administration is to whatever plan until such time as the stock is operational and or we see a significant shift in American relations with the Turks.

But we should get some good data points on all of that in the next two or three months.