An American, a Dutch, and a Japanese guy all walk into a bar…sounds like the beginning of a bad joke, right? Unfortunately for the Chinese, their semiconductors are on the shit end of this joke.

As the Japanese and Dutch join the US sanctions against Chinese Semiconductors, we find ourselves at a precarious crossroads. The semiconductor industry has long been the personification of globalization, with dozens of products crossing countless borders and supply chains longer than the DMV line. But what happens now?

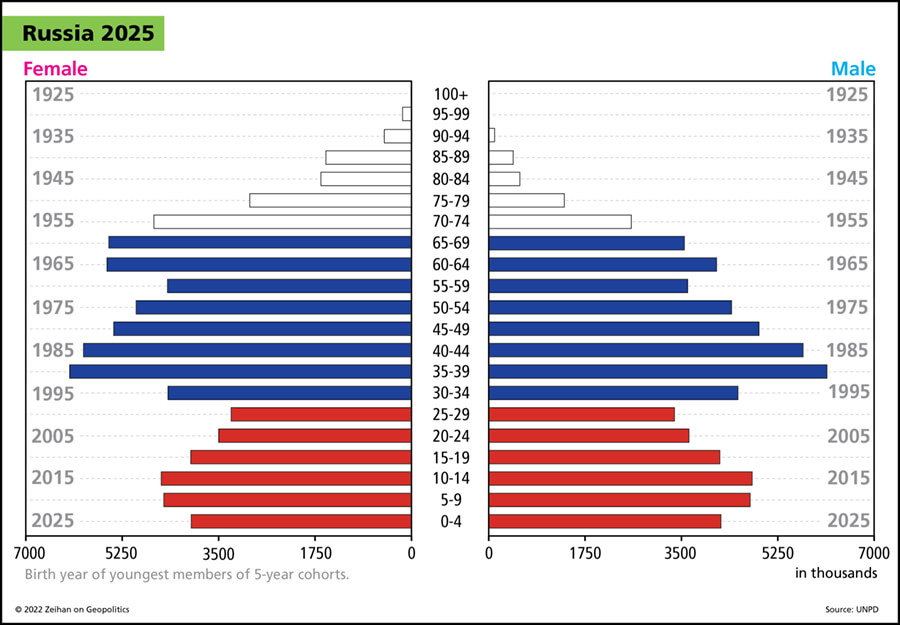

China’s demography is collapsing, and its semiconductor industry isn’t far behind. So someone else will have to step up and start producing these semiconductors; all eyes are on the US, the Netherlands, and Japan. Although, we may have to put up with middle-of-the-road semiconductors for a while.

Prefer to read the transcript of the video? Click here

Here at Zeihan On Geopolitics we select a single charity to sponsor. We have two criteria:

First, we look across the world and use our skill sets to identify where the needs are most acute. Second, we look for an institution with preexisting networks for both materials gathering and aid distribution. That way we know every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence. Then we give what we can.

Today, our chosen charity is a group called Medshare, which provides emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it. Until future notice, every cent we earn from every book we sell in every format through every retailer is going to Medshare’s Ukraine fund.

And then there’s you.

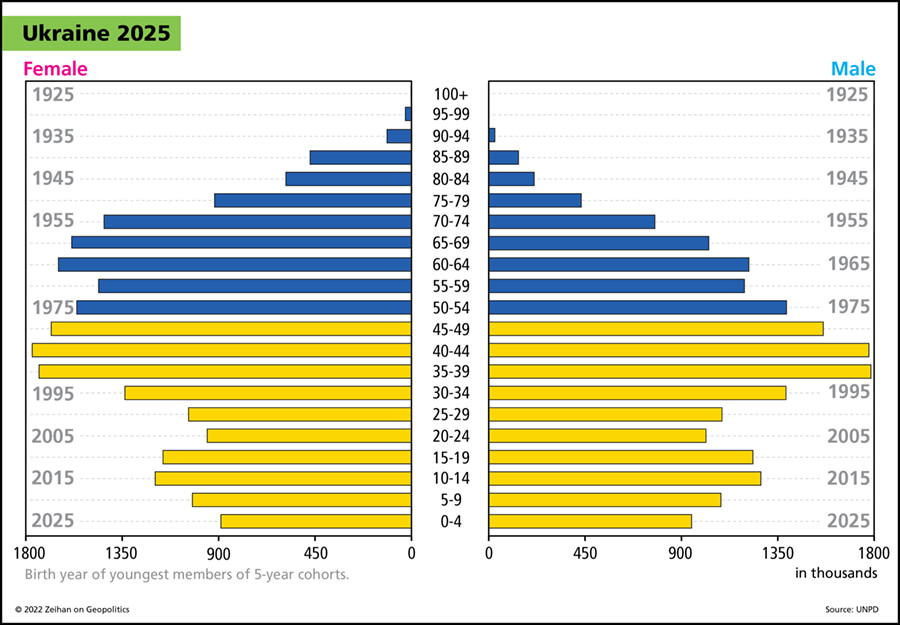

Our newsletters and videologues are not only free, they will always be free. We also will never share your contact information with anyone. All we ask is that if you find one of our releases in any way useful, that you make a donation to Medshare. Over one third of Ukraine’s pre-war population has either been forced from their homes, kidnapped and shipped to Russia, or is trying to survive in occupied lands. This is our way to help who we can. Please, join us.

CLICK HERE TO SUPPORT MEDSHARE’S UKRAINE FUND

CLICK HERE TO SUPPORT MEDSHARE’S EFFORTS GLOBALLY

TRANSCIPT

Hey everyone. Peter Zeihan coming to you for a very, very chilly Colorado. It’s a balmy negative seven degrees Fahrenheit right now. It’s the 30th of January and the big news internationally is that the Dutch and the Japanese have decided to join the American sanctions package against China for high end semiconductors. Now, there has been a lot of talk about how when the United States goes alone, it’s a problem with semiconductors, it just encourages other people to build alternatives and use alternatives.

That is hideously wrong for two reasons. First of all, the nature of the semiconductor industry is more of an ecosystem. There’s very few places that, without significant industrial buildout, could even pretend to do more than two or three steps of it, much less the dozen or so steps that are necessary to make sorry it is really cold. Are going to go down another layer here.

For example, the lithography, the wafer, manufacturing, the design, these are all done in different places and the hardware is built in different places and it all has to be brought together. Semiconductors are globalization given physical form. The idea that you can shuttle multiple products among multiple borders at any time and have long involved technical supply chains operating without interruption, and that’s computing in general. But for semiconductors specifically, all of the hardware needs to get to the same location and order than build the semiconductors. So you need lithography machines, which are fancy lasers that come from the Netherlands. You need lenses from Germany, you need optics from California, need designs from Silicon Valley and Salt Lake City. And you need wafer systems that come from Japan and so on.

So you remove one country from this ecosystem and the whole thing falls apart. So that means that the United States, should it choose to go it alone, really can stick to the Chinese or anyone for that matter. But so can the Dutch. And so can the Japanese. And so can the Koreans. And so can the Taiwanese. It takes the family. So that’s kinda piece one. Piece Two, is there was really never any doubt that the Japanese and especially the Dutch were going to join in the sanctions. And I know, I know, I know people are like, oh, their bottom line comes from China and corporations are not the same as governments. Well, I’m sorry, but it’s just not that clean.

The issue is you have to look at the locations of these countries and what they need to be independent, much less to thrive. In the case of the Netherlands, they’re the runt in the neighborhood. They may be a powerful economy. They may be very high valuated and technologically advanced, but they’re sandwiched between the Germans, the French and the Brits. And while the Dutch have a reputation for being brusque and abrupt, everyone in Europe would rather deal with them than the Germans or the French or the Brits. And so they become the middlemen of the European system. That is a very awkward place to be from a security point of view, because you never know when someone’s going to throw a war and you might get inadvertently invited.

So the Dutch have always tried to find a friend who’s not on the continent in the short term. That has always been the Brits, but they prefer a bigger friend who is even further afield, who cares less about the minutia of European affairs and just tries to keep the war from happening in the first place. That since World War Two has always been the United States.

And you can argue that. I could argue I do argue, that the Dutch are among the top five most loyal nations to American security interests because the Dutch know they’re going to need the help back home. So as soon as the Biden administration announced their semiconductor sanctions back in October, talks started with not just the Dutch government, but ASML, which is the company that does the lithography. And they were cordial and they were cooperative. And we now have an agreement that very soon the Dutch will formally be joining the sanctions system against the Chinese.

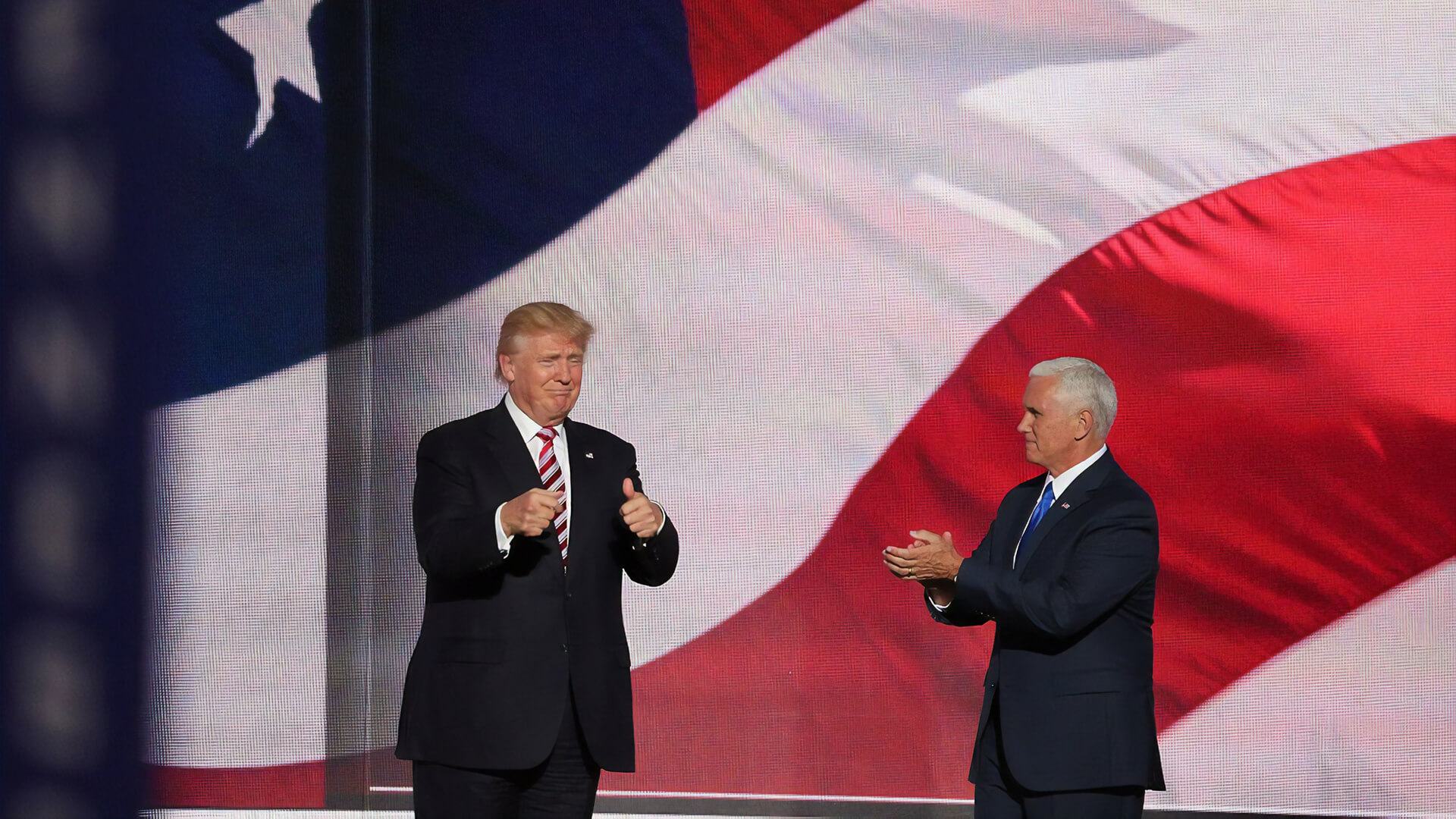

Now, the Japanese are a slightly different story because Japan used to be a great power not all that long ago. If you remember World War Two. But as their demographics have decayed, more and more industry from Japan has offshored to other places, most notably the United States. They want to have the production in a place with a strong enough demography to actually consume the stuff that they build. That’s changed the nature of the relationship. It’s far more co-mingled now than we have ever had with the Japanese and the Japanese have ever had with anyone. And so under a previous government, the Shinzo Abe government, a trade negotiators were dispatched to Washington to basically seek a deal with the Trump administration.

And the deal they ended up getting was humiliating. But they realized that was the price of a strategic partnership that could stick. And then when Biden became president, all other trade deals that were struck by the Trump team, other countries tried to back out, most notably Canada. Mexico tried out to get away from some of the terms of NAFTA to the Japanese, made it very clear to the Biden administration that they were not going to be on that list. They were happy with the deal as it was. And the Japanese are now the only country that has been able to strike deals on trade and on security with both the Trump and the Biden administration’s. Same terms, which means that Japan’s already made its bed. It has already decided that it has to be part of the American network. And so when the sanctions came up against semiconductors to China in October, honestly, it didn’t take much arm twisting at all.

So the Chinese, when it comes to the mid to high end chips, are just out of the game now. They can’t make any of this work. They’re going to be buying as many chips as they can for as long as they can, but they’re just not going to be able to advance past where they are right now.

The only country that’s kind of on the outs that has not agreed to join the sanctions in any meaningful way at this point is Korea. And it’s easy to see why they’re in a tough spot. They’ve got Japan on one side, which has colonized them many times. They’ve got the Chinese on the other side, which is a huge neighbor. And their relationships are, in a word, complicated. And, of course, there’s the North Korean question. In many ways, South Korea today is a bit like the Europeans of the last 30 years, desperate for security issues, to not figure into trade relations because they know they’re in a tough neighborhood. And when things crack, it all goes to hell very quickly.

So now the United States really only has one country to focus on. And so all its diplomatic heft is going to be going and looking at the Koreans to try to get them on board as well. And they’re the last ones I would expect for them to join the system later this year as well.

Now, the nature of making semiconductors, so there’s dozens of different types, but you can kind of put them to three big buckets. Your top tier, the best ones. These are ten nanometer and smaller. This is typically what’s in your cell phone or in your high end computers and servers. Those about 80% of them are actually fabricated in Taiwan, with another 20% in South Korea. But again, you need the whole ecosystem to make it work or move one country. The whole thing falls apart. In the middle, you’ve got everything that goes from climate control systems to automotive to aerospace to machinery. Those are made in a host of places the United States, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, China, the Netherlands, a little bit in Britain and Germany as well. This still requires the ecosystem, but you could probably lose one player, probably not more than one player. And then you get your low end, your 90 nano meters and up. These are chips that are basically analog processors. They can do one little yes no equation, not much more than that. This is the Internet of Things. And this, for the most part, is centered in the Chinese system. Now, the Chinese are the only country that makes the 90 nanometer chips. And this is a low tech enough chip that the Chinese don’t need substantial help from the rest of the world in order to do it.

So we’re going into a really interesting phase here. I would argue that for reasons of energy and agriculture and security and trade and personality and politics, that the Chinese system is in its final years. It’s going to collapse this decade. And I would argue that the globalized system that allows the great good chips, the ten nanometer and better to exist, that perfect situation of trade with no friction that that’s going away.

What’s in the middle that is a little bit more forgiving in terms of supply chain. That’s what’s probably going to last. So we’re going to lose the really good chips and the really bad chips. And what’s in the middle is just what we’re going to have to make do with until we can have a significant industrial buildout in the countries that already have most of the remaining steps. And the Japanese, the Americans and the Dutch are going to be the center of all of that effort.

Alright. That’s it for me. I’m going to go warm up. Take care.