The advanced developing world is about to have its moment. We’re talking about India, Turkey, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Brazil. These countries were a little late to the global scene, but now it’s their time to shine, hopefully…

The path to globalization is well-traveled, but that doesn’t mean its obstacle-free. These countries will have to work hard to balance their shifting demographics with changes to their economic structures and movement along the value-add chain.

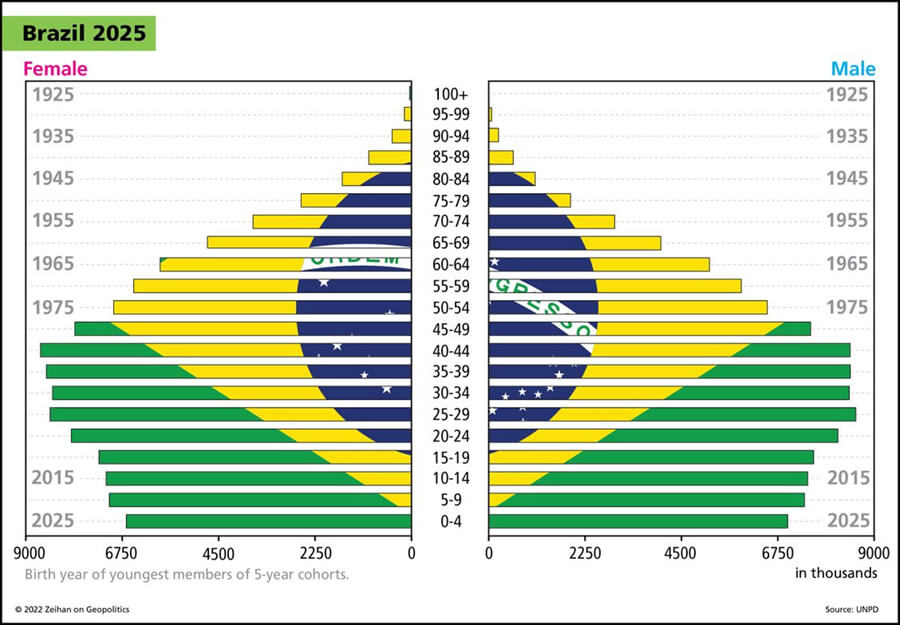

For a country like Brazil, their current trajectory could very likely send them into a crippling demographic situation with no way to pull themselves out. If a country like Turkey continues to move up the value-add chain steadily, I could see them flourishing in the coming years.

These countries are not facing a terminal demographic situation quite yet, but if history has taught us anything…now is the time for them to reconcile their declining demographics and prepare for what comes next.

Prefer to read the transcript of the video? Click here

Here at Zeihan On Geopolitics we select a single charity to sponsor. We have two criteria:

First, we look across the world and use our skill sets to identify where the needs are most acute. Second, we look for an institution with preexisting networks for both materials gathering and aid distribution. That way we know every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence. Then we give what we can.

Today, our chosen charity is a group called Medshare, which provides emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it. Until future notice, every cent we earn from every book we sell in every format through every retailer is going to Medshare’s Ukraine fund.

And then there’s you.

Our newsletters and videologues are not only free, they will always be free. We also will never share your contact information with anyone. All we ask is that if you find one of our releases in any way useful, that you make a donation to Medshare. Over one third of Ukraine’s pre-war population has either been forced from their homes, kidnapped and shipped to Russia, or is trying to survive in occupied lands. This is our way to help who we can. Please, join us.

CLICK HERE TO SUPPORT MEDSHARE’S UKRAINE FUND

CLICK HERE TO SUPPORT MEDSHARE’S EFFORTS GLOBALLY

TRANSCIPT

Hey Everybody. Peter Zeihan coming to you from Colorado. I am in training for my upcoming New Zealand trip and so I wanted to record a couple of videos that would last a little bit longer. So this is the most recent installment in our demographic series. And today we’re going to talk about the advanced developing world, a group of countries that includes India, Turkey, Indonesia, to a lesser degree Vietnam, certainly Brazil.

These countries have a lot of things in common, not just in terms of their demographic structure, but their economic history. So until World War Two, these were all either colonies or kind of isolated systems. And they had that traditional, pre developed world pyramidal structure that was very high consumption, high inflationary and relatively low value added. But even in the early decades of the post-World War Two era, they didn’t really join into the Bretton Woods free trade system, even though some of them, several of them were signatories to the pact. They kept their economies to themselves for nationalistic reasons. And to be perfectly blunt, there was a fair amount of the advanced world, most notably Europe, where even though global trade was available, they really didn’t globalized their supply chains. They were export products, but they tried to not become dependent upon anybody else in terms of the production cycle. Well, you play that forward until 1992. And what changed in 1992 is, of course, the Cold War ended. And that’s meant that a lot of the strictures that had made it difficult to do things went away. And these countries came in from the cold from a little bit a second in 1992, the Europeans signed the Treaty of Mashhad, which did away with a lot of the internal tariff and non-tariff barriers that existed within the European space. And that meant that the Europeans started to integrate and especially German supply chains started to link to the rest of Europe over the course of the next 20 years. That was extended first as economic links and later as full EU membership to all of the states of Central Europe, from Estonia down to Bulgaria, with Poland being the most important one. And that meant that the European space, or if you want to be honest, the German economy became suddenly this global powerhouse and started exporting products that were a lot more value added from a lot more product sectors. But most importantly, of course, 1979 was the year that the Chinese started to tiptoe into the international system and then really join in in the 1990s and 2000s, which meant that the Chinese were ravenous for raw commodities and would pay pretty much anything to get whatever they needed.

This all benefited the advanced countries of the developed world because they could get certain products from the Germans and the Chinese that they could make at home, and then they could work on either raw materials or manufacturing to fill in the niches that the bigger economies didn’t provide. So for most of this class of country, 1990 really was the break point where they started to urbanize and industrialize. It took the combination of not just the global trading system, but also a change in the way that other major economies viewed economics. In the case of Mexico. 1992 is when after was adopted and of course, the early 1990s when the WTO came into existence.

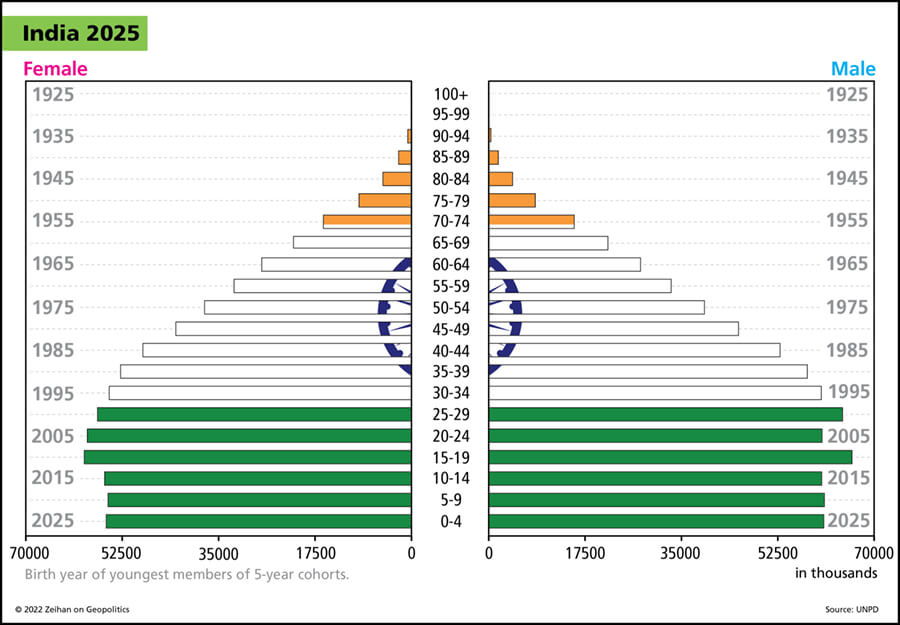

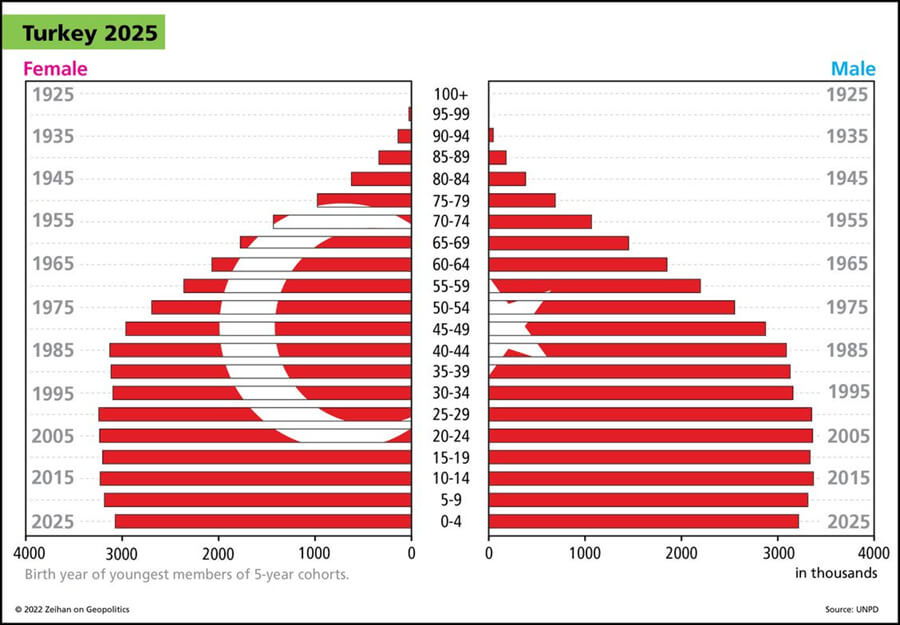

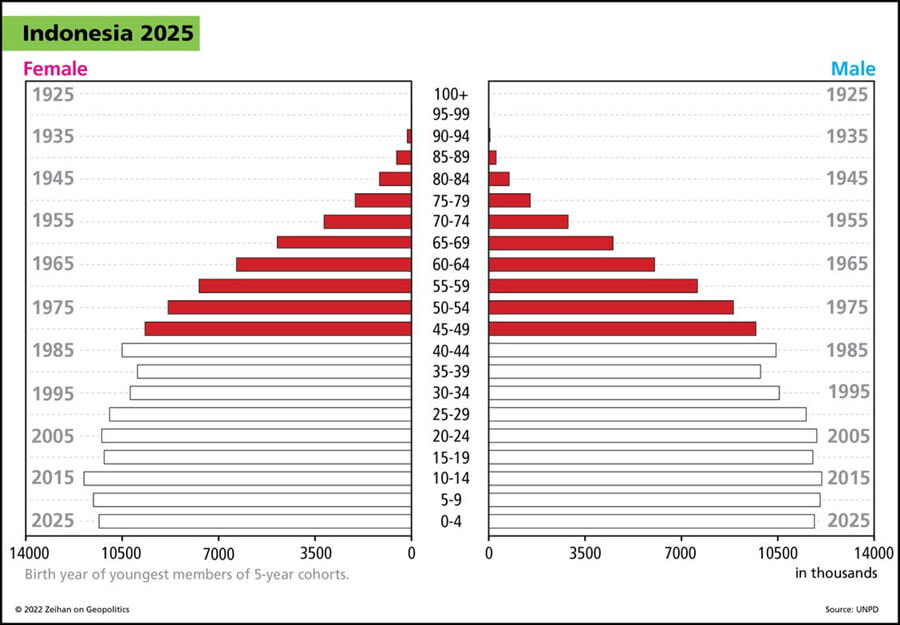

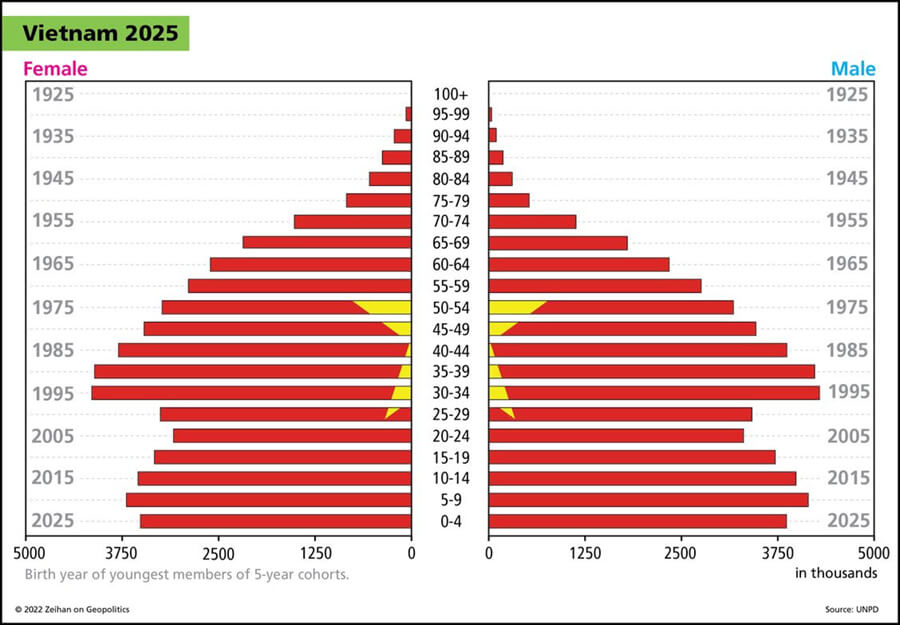

So what this means is that these countries started this rapid process not in the forties or fifties, like, say, the Koreans or the Japanese or the Europeans, but not until the 1990s. But by that point, the process of developing and industrializing and urbanizing was kind of old hat for a lot of the world. So these countries were able to proceed down that path a lot faster than the countries that have come before. So for the Brits, it took seven centuries. For the Germans, closer to five. For the Americans…America’s a special case, let’s leave them out. For the Spanish, it really only took 2 to 3. These countries have done it in really one, one and a half to two. And as a result, starting in the 1990s, their birthrates plummeted, in most cases dropping by half to two thirds. So if you look at the population structure of their demographics, it’s a pure a pyramid for people who are above about age 35 and then it goes straight down in a column. Now, this is hardly a disaster. By having fewer children, more money can be focused on education, on infrastructure, general business investment. And so all of these countries have been moving bit by bit up the value added scale. We’ll look at Mexico from a value add point of view, comparing the value of the inputs versus the value of the exports. It’s probably the most high value added economy in the world. So, you know, no slouches in any of these categories.

But this has some consequences because if this continues, these countries are going to age at a much faster rate than the countries that preceded them. So, you know, we’re talking about these countries reaching a mass impact in really under 20 years. And in the case of the United States, as a point of comparison, the U.S. is going to be a younger country, demographically speaking, on average, than Brazil in the early 2040s in Mexico and Indonesia are going to pass by us in the early 2050s and probably even India by 2060.

Now there’s a lot of history to be written between here and there, but these countries all have a demographic moment and if they take advantage of it, to become developed by moving up the value added chain very, very rapidly, kind of like Mexico is, then by the time they get to these points, they will be developed enough to deal with those sort of demographic consequences. But if they become stuck in the middle, which is definitely what seems to be happening with Brazil, they’re going to have some real problems because they’ll have gotten old without becoming developed.

The case of Brazil is a special one and it’s almost entirely because of China. The Chinese came in under President Lula, his first term, and they signed a number of deals to build joint ventures for producing products in Brazil. But the Chinese basically lied and stole all the technology from all the Brazilian firms and then took it back home, produces in mass and basically drove all the Brazilian companies out of the global market. So the Brazilian industry now only basically services the Brazilian system. Indonesia has not fallen prey to that because they didn’t have the technological aptitude in the first place. They’re trying to move up the value added scale, getting out of raw commodities into processing and ultimately into things like battery assembly, which is overall a pretty good plan, inconvenient for the rest of the world, who is trying to go green quickly, but definitely in Indonesia’s best interests. Mexico is definitely the furthest along overall and moving up the value added scale. And in terms of labor productivity, I’d argue they’re above Canada already. Who am I leaving out? Turkey? The Europeans have integrated with Turkey to kind of be the Mexico for Europe. And Turkey began with a much more sophisticated labor force and infrastructure than the Mexicans had in the 1990s. They haven’t moved as fast, but you have a much deeper penetration of these technologies in these skills throughout the Turkish system than in any other countries in this class. So if the Europeans were to vanish tomorrow, the Turks would obviously feel it. But they definitely remain the most powerful country in the neighborhood, and their demographics are young enough and their neighbors are even younger that I could see a Turkish manufacturing system really taking off. Obviously, this isn’t Germany would be the same quality, quality of product, but would still be a pretty good result anyway.

Bottom line of all of this is that these countries all had a moment, the historical moment that is approximately as long as the one we’ve just completed with the hyper globalization of the post-World War Two era. But it is still only a moment, and they all need to really buckle up and get down to business if they want to do well in what comes next.

All right. That’s it for me today. See you guys next time.