Let’s discuss what China’s potential invasion of Taiwan would look like.

Should China attack, both Biden and Trump have been explicit that the US would intervene economically and militarily. Beijing doesn’t believe that, though. Despite the echo chamber Xi Jinping has created, deep down, he knows that this invasion doesn’t bode well for them.

China lacks the logistical capabilities to move a large enough force effectively and efficiently across the Taiwan Strait, so Taiwan would have time to prepare, and it would become a shooting gallery. If they somehow managed to capture Taiwan, that would only be the beginning of China’s problems. China couldn’t operate the semiconductor fabs, supply chains would begin to collapse, energy and agriculture imports would falter…

Transcript

Hey all, Peter Zeihan here come to you from Snowmageddon 2025. We’ve gotten about ten inches, so far. We’re expecting another three before the stops. And if you this is my last video, you’ll know what happened. Today we’re taking a question from the Patreon page. A lot of people have been doing war games recently of the Chinese attack on Taiwan, simulating a combined naval and cyber attack.

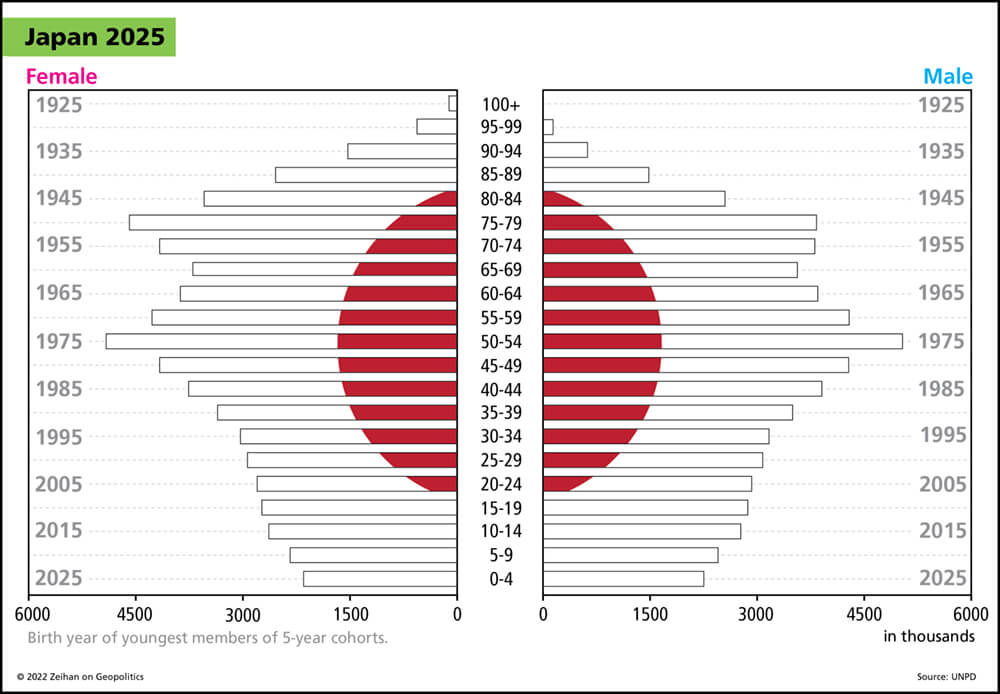

And what do I think of their prospects for Taiwanese success? And how do I think the United States, and especially Japan would respond?

Under the Biden administration and now under the Trump administration, the American policy on Taiwan has actually been shockingly clear. It used to be we had something called basically deniability, where the United States deliberately said that it could neither confirm or deny any particular action.

We called Taiwan a significant entity and a friendly entity, but not a country that has pretty much gone by the wayside. Now, while there’s not a firm bilateral defense treaty between Taiwan and the United States, both Biden and Trump have said very similar things that if there was an attack, the U.S. would intervene militarily and economically. Now, that is not believed in China.

In China, the belief is at most they’d have to face some mid-level sanctions, kind of like what the Russians are dealing with with the Ukraine war. But let’s review a few basic facts. Number one, if you think the Trump administration is echo chamber, it is nothing compared to what’s going on in the People’s Republic. Chairman XI purged his last real advisors eight years ago.

And so anyone who’s repeating the party line is doing just that, repeating the party line. And if you want to get in, good. Well, if you want to get in dead with Chairman XI, the best thing to say. So yeah, Taiwan is a real place. We shouldn’t invade that. That’ll end your career and several other things related to your life very, very quickly.

Second, it’s a bit of a hop across the Taiwan Straits, over 100 miles. And, the seas are often relatively stormy. So if the Chinese were to pull this off, they would have to build a really large amphibious force. And they are working on that. But the time it would take to merge forces into the zone across from the Taiwan Strait and meet them up with their equipment and then sail them to the few points in Taiwan that you can actually land safely.

That’s a whole other question. It would take weeks, if not months for the Chinese to arrange. And in that time, anyone else in the world could choose to do something. Most notably, the Taiwanese and Taiwan has had a nuclear power reactor for as long as I’ve been alive.

So if the Taiwanese decided that they needed to build a few crude nuclear weapons to dissuade the Chinese, that is something that is well within their technical skill set. Third, let’s assume that none of this is relevant, and that the Chinese and the Americans do not intervene militarily at all, even though it would be an absolute shooting gallery taking out all of these troop transports, which are most of which are just civilian vessels that would be attempting to cross the Chinese strategy is literally to shove a million people in the boats and just kind of sail that way.

It’s not a good plan, but let’s assume that it works. Then what, the Chinese can’t operate their own semiconductor fab facilities. There’s no way they can operate the Taiwanese ones, nor would they even get the plants, because those come from Japan or the United States. So the question then would be, what happens on the next day?

Remember that the Chinese navy lacks reach. It is designed around the goal of capturing Taiwan, and it would probably be a real sight. But it’s not designed to project power, much less control ceilings. They just don’t have the range. They have a lot of ships, but they’re small and their legs are short. So you put a few ships in the Indian Ocean, maybe in the general vicinity of Malacca, and you cut off the energy artery.

That’s where two thirds of their energy comes from. You do a few targeted strikes on things like pipelines, and all of a sudden you’ve got a country that imports 80% of its energy, having very little, if any. And that assumes the United States doesn’t do a cyberwar back. So, Chairman Ji, a decade ago knew full well that any meaningful attack on Taiwan is not just the beginning of the end of China’s of strategic power.

It’s the end of China as an entity. It’s the end of the Hun ethnicity because of energy shortages and famine, because this is a country that imports three quarters of the stuff that they need to grow their own food. And so the decision was made to proceed because for nationalist reasons, they can’t do otherwise. But I really don’t see the strategic math of changing very much.

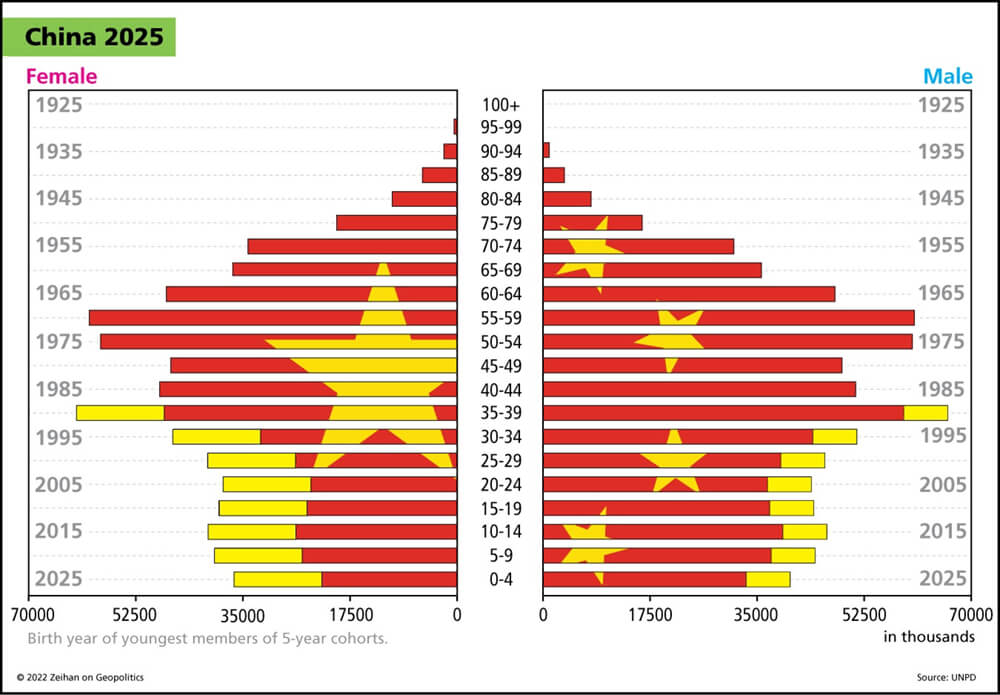

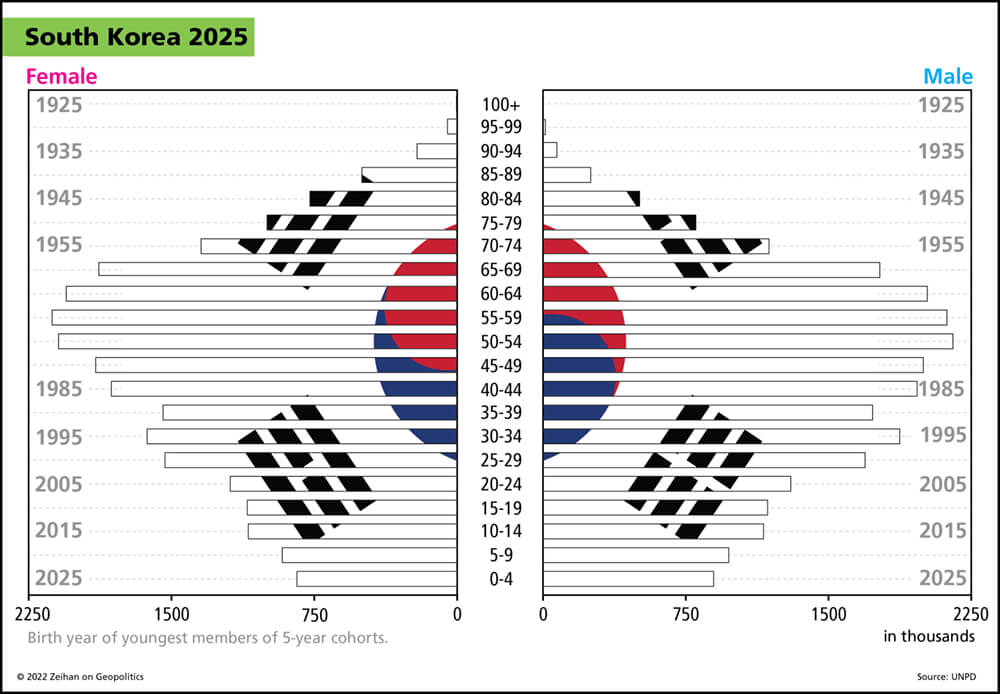

All that’s changed is that China today is more dependent on international trade than it was 15 years ago, because 15 years ago, they at least had some people who were, you know, age 40 and under. Now they really don’t have many at all. We’re in the final decade, and if the Chinese are going to try something, they’re probably going to do it in the next decade.

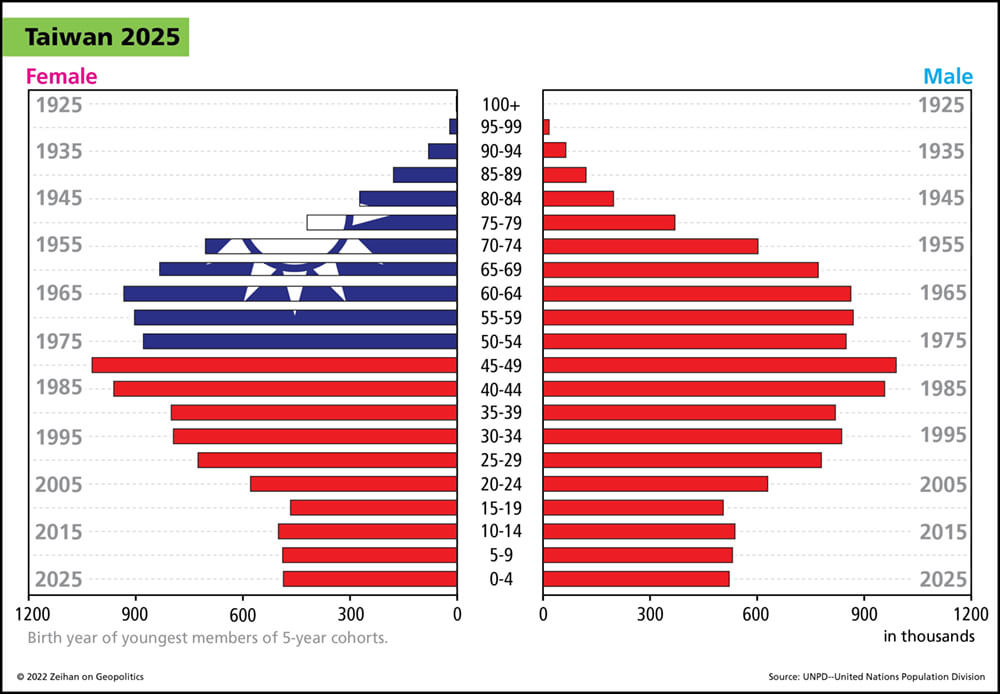

But if they do, they will be accelerating their utter end and removal from history, because they’re just won’t be enough energy and food to keep what’s left of the population alive. Do I worry about Taiwan? Not really. Does that mean I think semiconductors are safe? Absolutely not. The semiconductor supply chain is the most diverse and fragile thing in the world, and we only have lose one country of significance to globalization or depopulation.

And the whole thing falls apart. I normally point at Germany is the country I’m most worried about, but as long as we’re talking about China and Taiwan, let me point at China, because they do the processing for a lot of the materials that go into everything. This industry really does take every one, and there’s no version of globalization that can take place over the next 15 years, where we don’t lose the ability to make those high end chips at all.