My fourth book, The End of the World Is Just the Beginning: Mapping the Collapse of Globalization is scheduled for release on June 14. In coming weeks we will be sharing graphics and excerpts, along with info on how to preorder.

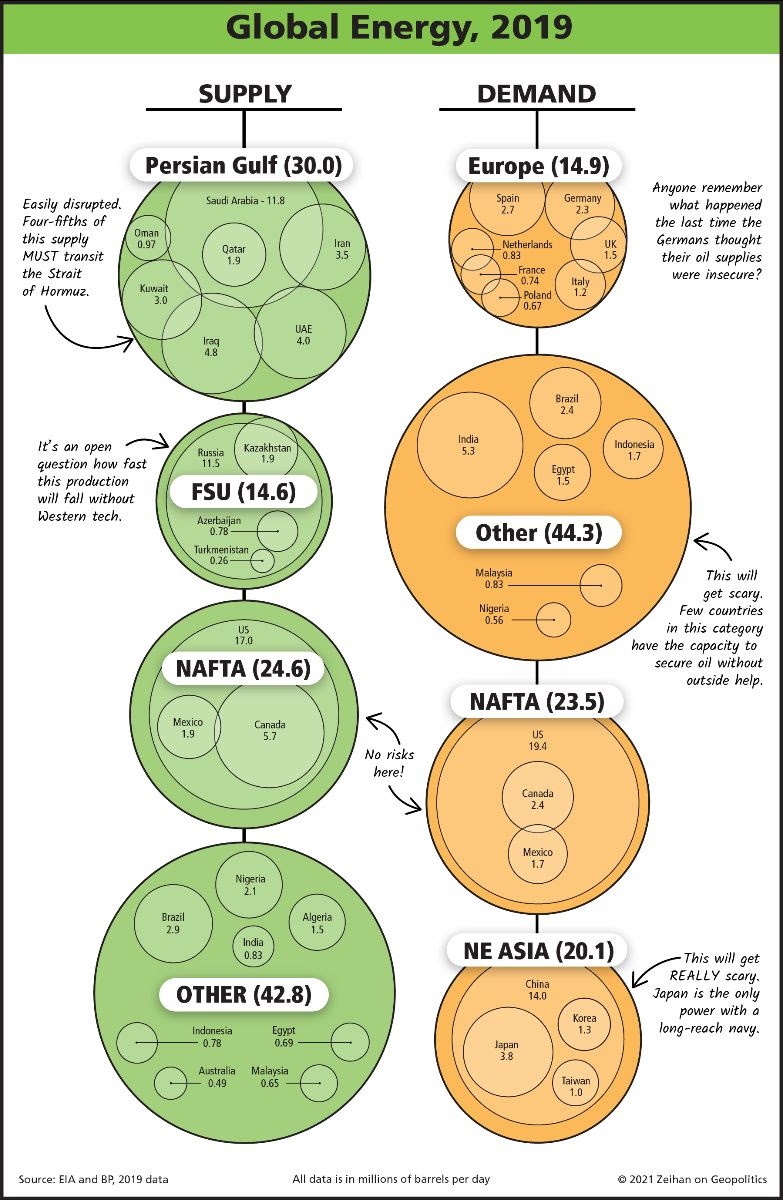

Former Soviet states supply over 14 percent of the world’s energy. In this graphic from my new book, The End of the World is Just the Beginning, I ask the question: how long can former Soviet Union countries’ oil production last without Western technological assistance? Russia has invaded Ukraine and, just like that, we are going to find out the answer. With both Western oil majors and service companies heading for the door, we are already seeing lowered oil production. At the time of writing, the International Energy Agency forecasts that from May, nearly 3 million barrels a day in Russian production will be turned off.

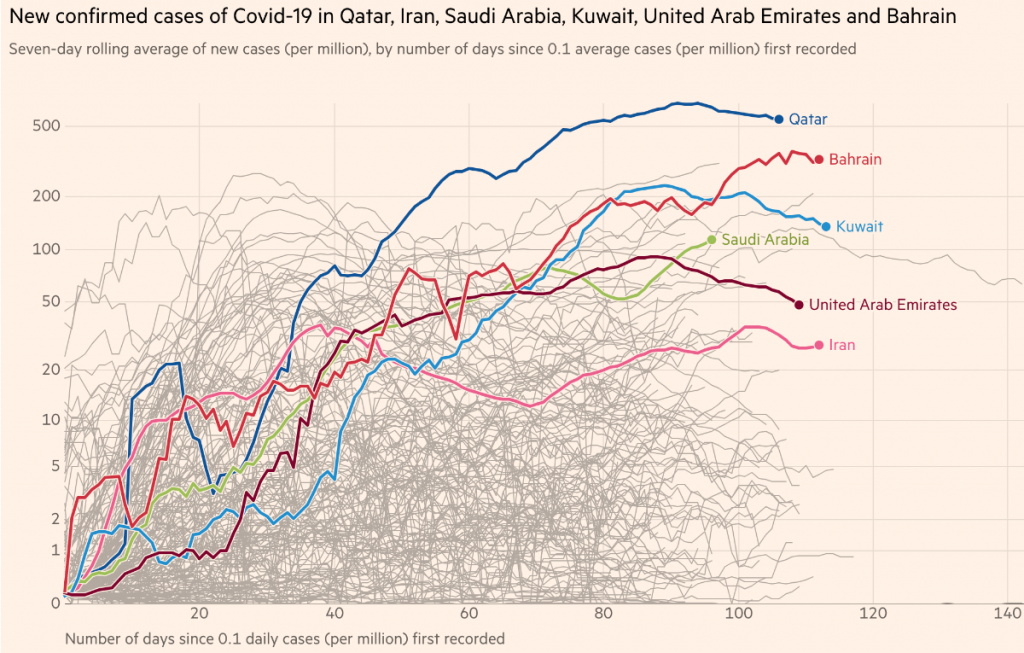

With Russia’s production dimming, the world will look to the Persian Gulf for more oil and gas. Turning to the Persian Gulf, however, is simply swapping one conflict zone for another. Four-fifths of the Persian Gulf’s supply transits the Strait of Hormuz to reach its destination. Piracy can always be an issue. High food and agricultural input costs increase the possibility of social unrest in the region. In short, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine further destabilized an already unstable market.

As you can see, NAFTA supplies more gas and oil than it consumes, which is the ideal scenario. On the other hand, Europe, excluding the former Soviet states, cannot domestically satisfy its energy needs and is forced to rely on increasingly unstable import sources. Northeast Asia is in the same, if not more dire, boat. The EU at least has navies large enough to go out and secure its own oil. In Northeast Asia, only Japan has this capability.

To learn more on this topic make sure to look out for my upcoming book, which will be released June 14. We encourage those who can to preorder by clicking on the link below.

Here at Zeihan On Geopolitics we select a single charity to sponsor. We have two criteria:

First, we look across the world and use our skill sets to identify where the needs are most acute. Second, we look for an institution with preexisting networks for both materials gathering and aid distribution. That way we know every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence. Then we give what we can.

Today, our chosen charity is a group called Medshare, which provides emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it. Until future notice, every cent we earn from every book we sell in every format through every retailer is going to Medshare’s Ukraine fund.

And then there’s you.

Our newsletters and videologues are not only free, they will always be free. We also will never share your contact information with anyone. All we ask is that if you find one of our releases in any way useful, that you make a donation to Medshare. Over one third of Ukraine’s pre-war population has either been forced from their homes, kidnapped and shipped to Russia, or is trying to survive in occupied lands. This is our way to help who we can. Please, join us.