American reindustrialization was always going to be painful process, but there were several ways to soften that blow; the biggest of which was our trade relationship with China. At least, it was.

The tariff situation that began in April soured our relationship with the Chinese. Since then, they’ve halted exports of rare earth magnets, a crucial component in…well, basically everything important. A quick disclaimer/history lesson: rare earths aren’t all that rare, they’re just difficult and time-consuming to extract. The Chinese subsidized the sector beginning back in the 80s and made it illogical for anyone else to try and compete. Hence China’s dominance in this field.

Now, the Chinese are dangling that rare earth carrot in front of Trump. Unfortunately, the American industrial base must be rebuilt for a whole lot more than just rare earths. Something that a little strategic foresight would have helped with.

Transcript

Peter Zeihan here, coming to you from Colorado. Today we’re going to talk about the status of the US-China trade talks and where the United States is with its re industrialization. And the short version is things going really badly. If you remember back to the first week of April, the Trump administration put a 55% tariff on everything coming from China.

And then we got into a shouting match with the Chinese, and that number went up and up and up and up until I think we had 185%. And then a couple of months later, we had a bit of a truce and the numbers went back down to 55%. What’s the best way to go through this? So the issue at the moment, right now is that China is refusing to export rare earth products, most notably magnets, to the United States.

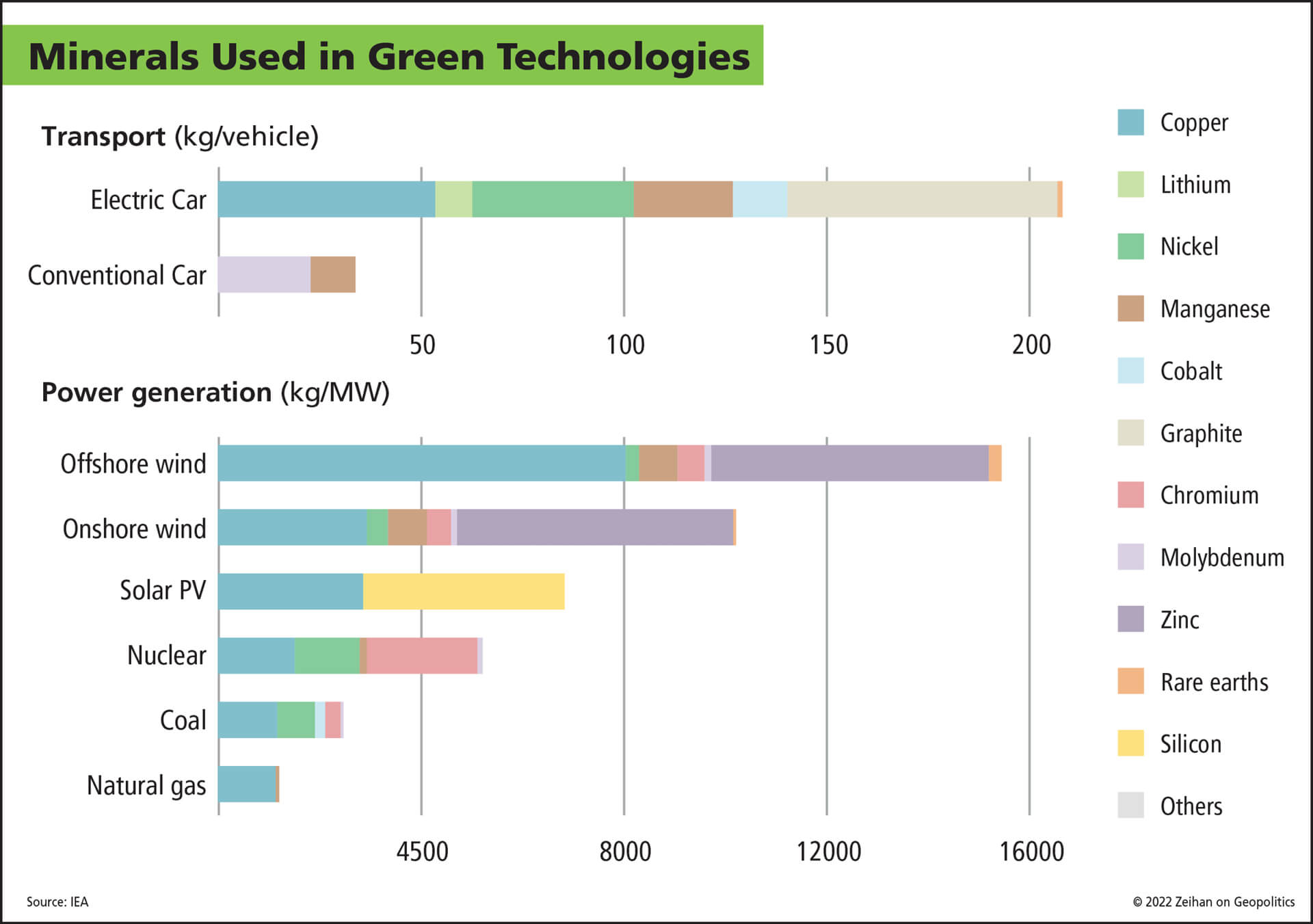

And these magnets are used in any number of electronics, aerospace, and especially automotive parts. Rare earths are a group of materials that are relatively difficult to source not because they’re rare, but because they’re not present and particularly high concentrations. So if anyone says that there’s a rare earth mine coming online, that’s a good indication that you should just completely ignore that person because there is no such thing rare earths are produced as a byproduct of other metals purification and refining.

So you have a silver mine, you extract the silver, you then use the tailings and go through and extract the rare earths. And the same thing for copper and gold and bauxite and all kinds of other things. There’s like a dozen rare earths anyway, extracting them and purifying them is not particularly difficult. It’s just that the concentrations are low.

So it requires several steps, several hundred steps. And the rare earth materials themselves share a lot of chemical properties. So you have to basically separate them from one another as well, which is where most of the time takes. So you take these tailings, you grind them down, you add some chemicals to dissolve everything, and then you basically boil the whole thing in acid.

And that separates a little bit out. And then you take that and you put it into the next batch of acid, and you do it again, and then up and again and again. And you do that a few hundred times. And at the end of the day, after usually 6 to 8 months of separation and acid treatments and starting with several tons of material, you get a couple of ounces of rare earth metals and a little goes a long way, for most uses, these things are really just doped rather than the core production level.

So, you know, all the rare earths that are used by the entire world could probably sit in a garage, every year. Anyway. It’s expensive, from a minerals processing point of view. And it’s dirty because of all the material that is used because of all the acid and because the radioactivity that naturally comes from a lot of mining activity.

So what happened was back in the 1980s, most of this stuff was done in the United States or in Europe. But the Chinese, who were early in their economic development, had decided that anything that you could throw cash at and anything where they could ignore environmental regulations, they would have an advantage in. So they threw a lot of money at this industry in order to dominate production.

And in doing so, because of the subsidies, they ended up producing the rare earths for significantly lower price point than anyone else could. And because of that, we were able to use rare earths and things like rare earth magnets in order to make what we call computers today, specifically solid state drives. For those of you who are older and you remember the old spinning hard drives.

Yeah, they didn’t use many rare earths, but the solid state drives did so the whole point was, now that we have this available, we’re going to move to a type of technology that uses much less electricity generated by far less heat, and sets the stage for the processing and computing revolution that we’ve known throughout the 90s and the 2000.

For example, smartphones wouldn’t have happened without this. So the Chinese have honestly done this a solid. However, over the 2000s and especially into the 20 tens, the Chinese got into rare earth material manufacturing, which is a significantly more sophisticated step, and simply purifying the rare earths. And that’s where the magnet stuff comes into play. And over the last 15 years, they’ve basically dominated that space and they’re refusing to export the metals to everybody else so that they can do the manufacturing.

And now they’ve dominated the manufacturing and they’re refusing to export the manufactured product. So this is a very real crimp, in the trading system and a very real point of leverage for the Chinese. Now, nothing that I have just told you is a mystery in the sector, whether that is computing or automotive or mining or metals purification.

But it is all news to the Trump administration. Remember that normally when a president comes in, he brings somewhere between 1300 and 3000 people in with him to stock the senior government. Trump’s brought no one. He just fired all the people who were there before, because he really doesn’t like anyone to remind him, even indirectly, that he might not be the smartest person in the room on every single topic.

So if anything that I just told you was news, that’s because you’re not an expert in metals refining a computer manufacturer. Neither am I, but I talk to a lot of people I know what I don’t know, and I seek out that information. And Trump is not a person like that. So what happened with the trade talks is Trump on April 2nd made these big announcements with those big game show boards and then just assumed that everything would magically happen the way he had dictated, regardless of what the situation on the ground was or the interests of other parties.

It was very Obama asked. Honestly, the two of them are very similar from their management style. Anyway. What this means is that even though the United States holds probably 90% of the cards in any meaningful trade talk, the Trump team is so small and is so siloed in what they do now. And then, of course, is hobbled by their boss that they can’t develop the staff.

It’s necessary to keep them informed on things like this. And so the Chinese system, even though they hold very few cards, they know where those cards are and they’ve played them very effectively against the Trump administration and basically brought American auto manufacturers to the brink of collapse by metering out this one little product, which is a point of leverage that they have.

The smart play is if you’re going to pick a trade fight, the first thing you do is start building up the alternative infrastructure that you need. When stuff on the other side goes away. And so in this case, luckily some of that work has already been done. So about 15 years ago now, the Chinese tried a similar trick with restricting rare earth exports to Japan when they were having a spat over something, and the Japanese figured out over the course of the next nine months how to use three quarters fewer rare earths.

Because, you know, for the last 20 years, the Chinese have been dumping it on the market below cost. So everyone just kind of gorged on it and no one really worried about using less. While the Chinese figured out ways to use less, they did the same thing with the Russians when it came to Palladium anyway.

Well, the Japanese were doing that. Everyone else realized that there could be a supply shock here. And so they built out a lot of the physical infrastructure that was necessary to process rare earths. We did it here in the United States. The Australians did it, the Malaysians did it, the French did it. And what’s happening now is some of that infrastructure is spinning back up because this is now an issue of the day.

Again, we didn’t operate it until now, because the Chinese were subsidizing it. So there was no point now that it’s a national security issue, that the math has changed and people are turning all that old infrastructure on. But the next step is going to take a little bit more work. Turning the finished material into manufactured intermediate products like the magnets.

That will probably be a little bit more involved than simply turning on some metals refining. I can’t give you a timeframe for how long that will take, because this is not something that has been done in the United States in a while. And unlike the, metals refining, where it’s an issue of no more than a year, we don’t know what the time horizon will be for bringing it on online, but this is one of probably 3 or 4 dozen things where the Chinese have done some version of this that needs to be rectified.

If the United States is going to prepare for whatever is next. If you’re one of those people who would like to think that the trade situation is going to revert to how we were 15 years ago, I mean, I think you’re wrong, but we would need this in order to prevent any sort of regression or long term fights with any partner, most notably China.

And if you’re like me, you’re pretty sure that the globalized system is never coming back. Then we need to do this regardless if we’re going to have stuff like, I don’t know, cars or we need to invent technology to get along without the rare earths one of the two. Anyway, this is all stuff that should have been done before we picked a trade fight and before the Trump administration demonstrated that they really don’t have a good grip on the core issues that are necessary to invent the next world, whatever that happens to look like.