I normally try to stay out of American politics. My work is in the wider world, the American system is remarkably stable and self-regulating, and if I’m to be completely honest, making domestic political forecasts tends to burn bridges no matter how even-handed I attempt to be. Case in point: many responses to my most recent newsletter on the American political system deepened my appreciation for creative expletives. And yet the 2020 general elections are only a few weeks away and their results are among the most hotly anticipated geopolitical events in years. It would be weird for me to not say anything.

Before proceeding, let me dispose of my personal politics. No one who espouses my particular mix of views on economic and social and global issues is on the ballot (and they weren’t last time, or the time before, or the time before that) so this newsletter isn’t so much an assessment of political positions with an endorsement or condemnation, but instead an explainer of where things stand along with a forecast for how both the elections and their aftermath will shake out.

Let’s begin with the incumbent:

In terms of international relations, perhaps Trump’s greatest presidential failing is his preference for personal deal-making as opposed to institutional diplomacy. What made Trump a successful real estate and branding magnate was his willingness and ability to shift responsibility – financial, legal or otherwise – around among different parties as part of his brokering.

In business, Trump’s method worked because the United States has a robust civil society, rule of law and multiple levels of government with investigatory and enforcement power. In essence, in his business negotiations Trump maneuvers the folks on the other side of the table into positions where state and the society do much of his work – and nearly all his enforcement – for him.

But the world is not the United States. There is no global, multi-layered, professionalized, largely-apolitical cadre of institutions to enforce agreements among countries. What few global institutions do exist share three fatal flaws:

First, such structures only have enforcement mechanisms should member countries choose to allow them enforcement mechanisms, often on a case-by-case basis. For example, the International Court of Justice’s rulings are technically binding, but any country can choose to withdraw enforcement power selectively or wholesale at any time for any reason. There aren’t many rules to rely upon. Only unenforceable norms.

Second, pretty much all global institutions were American-crafted as part of America’s anti-Soviet Cold War efforts. They only work if the US forces them to work, and between the gradual disengagement of Presidents Bill Clinton and George W Bush, and faster disengagement of Barack Obama and Donald Trump, they simply no longer function.

Third, in global affairs, the people on the other side of the table – Russia’s Putin and China’s Xi come to mind – have a lot more experience in breaking norms to their advantage. Both to a degree built their systems around such tactics. No wonder Trump often appears outmaneuvered.

Yet even bilateral deals where such squishiness is less common tend to be weak. It too is an institutional issue, although in bilateral agreements it has more to do with tasking and executive leadership. For example, in the final decade of the Cold War, Ronald Reagan negotiated a series of “trust but verify” nuclear disarmament deals with the Soviets. After the deals were signed Reagan didn’t simply leave to watch the Sound of Music, his administration worked out the monitoring details with the Defense Department, the State Department, the CIA, and the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. Enforcement did not magically happen. TeamReagan had to make it happen, and that required engaging not simply the Soviets, but multiple pieces of the American executive branch as well.

Trump simply ignores such empowering minutiae. After announcing his big deals, he moves on to something else and rarely looks back. That’s a big part of why his pacts with North Korea fizzled within months or why the Phase One deal with China was dead on arrival (in China). About the only exceptions have been TeamTrump’s trade deals, but here institutional involvement not only helped make the deals happen, but helped make them stick. The same institution responsible for negotiating the successful trade deals with South Korea, Japan, Mexico and Canada – the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative – is also responsible for enforcing the deals.

From my point of view, the Trump administration has been a missed opportunity.

Nearly everything about the American strategic position – from military procurement to diplomatic positioning – is a hangover from the Cold War: The prime operating principle guiding America has been that the United States will create a safe, globalized world that empowers weak countries and fosters global trade for all, and in exchange Washington gets to direct everyone’s security policies in order to better combat Moscow. The security-policy aspect stopped working when the Soviet Union collapsed, but the Americans never changed the script on globalization and kept holding up the world’s collective ceiling. American foreign policy became ossified and rudderless.

Trump, as a geopolitical neophyte unburdened by commitments made in the previous century, had the opportunity to come up with something new. He certainly proved eager to sledgehammer previous structures and relationships, but he – like his three immediate predecessors – failed to generate a replacement.

“America First” isn’t a policy, much less a strategy. It’s a motto. It’s just like Obama’s “don’t do stupid stuff”. And so I put Trump into the same basket as Obama: leaders who left the country worse than they found it. And that’s before considering Trump’s preference for playing fast and loose with ethics or institutions.

Now, the challenger:

Biden’s first problem is that he is a black box from a policy point of view. Biden is commensurate political chameleon. His position shifts on every issue based on what he perceives the majority of power brokers within the Democrat Party currently believe. That has put him on both sides of nearly every issue of importance during his long tenure in politics. Such flexibility is particularly problematic on topics where consistency is key, such as national security and trade issues. Such an unfettered lack of convictions is part of what led former Defense Secretary Robert Gates to note that Biden has been on the wrong side of every foreign policy and strategic issue of the past four decades.

Biden’s second issue is his utter lack of leadership experience, which I realize sounds odd considering he has served in Washington since 1973. But aside from two years as a legal clerk and lawyer, he had only been a senator before becoming VP. To be blunt, senators suck at being president. They have little concept of how to manage an organization – such as the federal government with its three million employees.

Nor did Biden’s tenure as Barack Obama’s vice president provide him with many leadership opportunities. This is most definitely not Biden’s fault. Obama was famous for hermetically sealing himself in the White House and only allowing in information that supported his penchant for non-action, and his near-pathological unwillingness to have conversations with…well, anyone. But Obama refused to let policy be made without him, leaving Biden with little to do for eight long years.

(Incidentally, similar issues constrained a far more straightforward and ambitious member of the Obama administration: Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. Part of why Ms Clinton resigned at the end of Obama’s first term is that Obama melon-balled out of the State Department control of diplomatic relations with the world’s most important countries, transferring their management to the West Wing where…nothing happened.)

The most positive thing I have to say about Biden’s expertise is the odd combination of his lack of convictions combined with having a boss who didn’t like to interact with others meant that whenever the Obama White House needed a mediator in Congress, Biden was the obvious choice. That’s great. That’s essential. I don’t think I’d call that leadership.

But I think, for me personally at least, the issue of mental competence is Biden’s biggest looming issue. Being gaffe-prone doesn’t bother me, especially when a gaffe-prone person owns it as Biden historically did in the Senate. I find it humanizing. Even credibility-building. I’m instead talking about something more concerning: I’ve lost track of the number of times of late that Biden has stumbled over his words or looked confused, even when reading pre-prepared remarks from a teleprompter. I had the opportunity to meet Biden shortly after the Obama administration ended and my first thought was “Wow. He might…he might have dementia. It’s a good thing he didn’t run for president.”

Yet here we are. I want my president to be able to handle a crisis. And foreign leaders. And the press corps. And a phone call. Due to his disposition, Trump has repeatedly demonstrated he cannot do these things well. Biden’s recent track record suggests something potentially even worse.

Despite Biden’s lack of consistency or experience and concerns for his mental capacity, many hopeful for (or resigned to) a Biden administration believe this can still work out. They say that, sure, Biden might be a keg short of a six pack, but so long as he has a strong cabinet everything will be fine. I’ve heard this argument before. Recently. It is what old-school Republicans hoped about Trump back in 2016. It didn’t work out very well. At the end of the day, the president has the power and you need to trust the person in that position, not his unelected handlers.

So we’re left to choose between two seventy-something men who feature different flavors of incompetence. I have no idea who I am going to vote for.

But I’m still, well, me. So I will make a prediction:

President Trump’s seemingly deliberate and always callous mismanagement of the coronavirus crisis has contributed to the death of 200,000 Americans. In per capita terms that’s double the suffering of Europe or Canada. In absolute terms that’s higher than the number killed in any American military conflict save the Civil War and World War II itself. Forget vaccines. Forget ventilators and masks. Forget the CDC and the WHO. Forget the PR war with the Democrats. All Trump needed to do to mitigate the risk was say something like “wear a mask, maintain some distance, and look in on your loved ones”. Paraguay managed it. Bulgaria managed it. This isn’t hard. Most of America’s political middle finds Trump leadership lacking and his behavior disgusting.

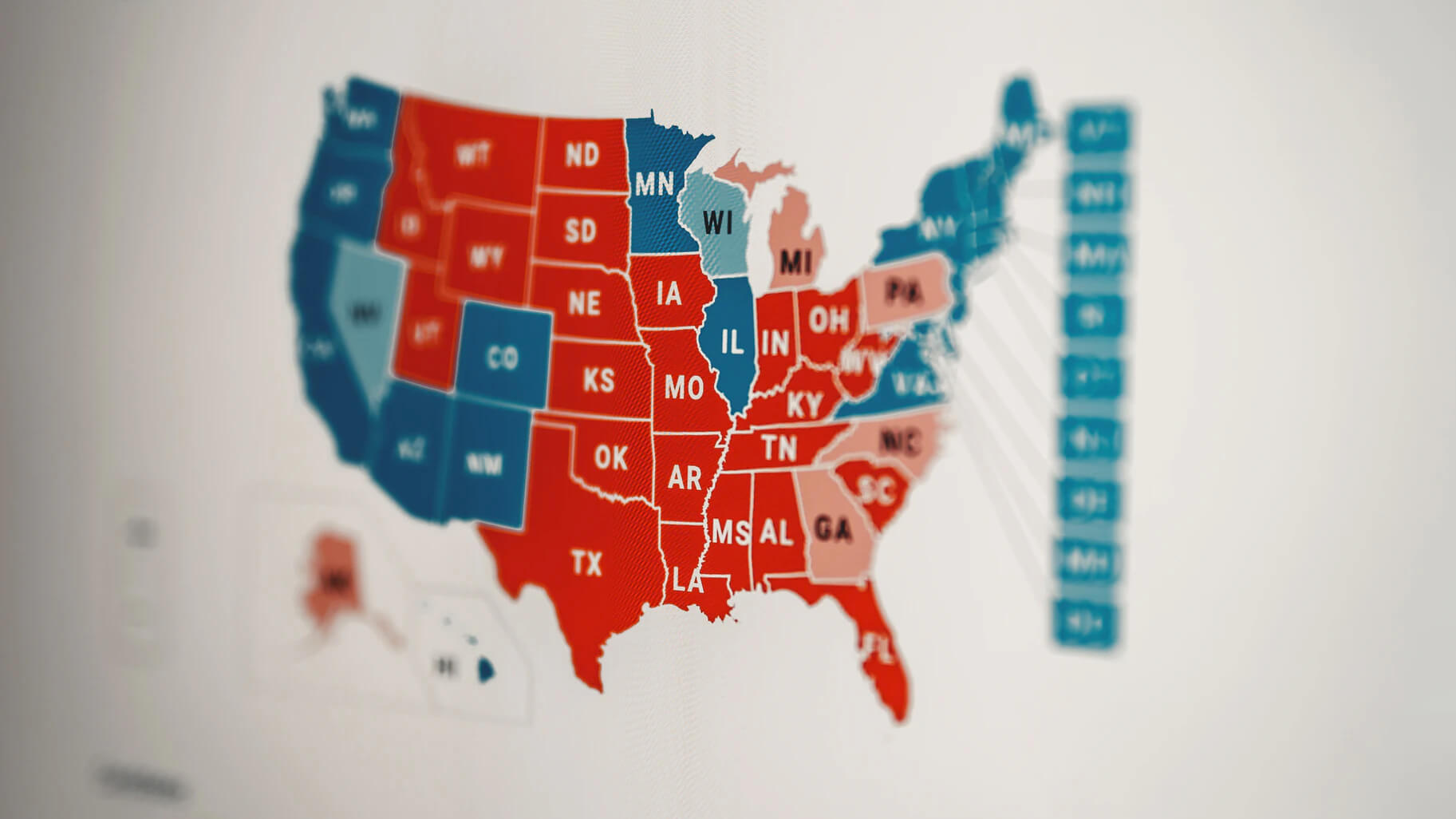

Trump also faces danger on the Right. Trump has alienated fiscal conservatives, the military and the business community – all once bedrock Republicans. The Democrats have avoided – albeit narrowly – running an absolute whackjob and instead settled on Milquetoast Biden. To achieve reelection, Trump must capture every swing state as well as a couple decent sized blue states. That’s just not possible. Trump surprised last time because there was a large block of voters – the populists – the pollsters missed. That’s not the case this time around. And so Trump will lose and he will lose big.

Assuming, that is, Biden can prove he still has some marbles.

Biden has been the most closely managed candidate in modern American political history. He has not been without his ring of protectors for two years, giving him the feel of a badly operated marionette. Americans need to know if he can function, and we will all find out together on Sept 29.

Next Tuesday will be the first presidential debate, moderated by Chris Wallace. It will be the first time Biden will need to hold his own in a long-form open forum without his support crew. His performance will determine the election. Biden does not need to best Trump in the debate. All he needs to do is come across as marginally capable.

If Biden can do that, concerns for his mental capacity will ebb and he will win handily.

If the Biden who served in the Senate for three decades shows up – a likeable, master debater who can identify with people with a glance and laugh at his own missteps – he will win in a landslide.

But if Biden just…can’t, then Trump walks away with it all.

It really is that simple.

Now I’m sure that many of you are either cheering my wisdom or burning me in effigy (maybe both for some of you), so let me now say something certain to piss everyone off at once:

As regards global affairs, who wins November 3 really doesn’t matter.

Yes, the U.S. President is the single-most powerful person in the world, but ultimately the United States is fundamentally incapable of moving forward on the world stage.

Another four years of Donald Trump would grant us the clarity of a known quantity: continued degradation of the structures of the international system. But that system has been degrading since 1992 so I don’t see this as more than a few additional steps down the same road towards a sort of retrenchment / neo-isolationism. That’s ultimately where I saw the United States heading back when I wrote the Accidental Superpower back in 2014.

A Biden administration would be little different except in tone. Resetting American foreign policy in any meaningful way first requires a replacement for the Cold War structures which are now three decades out of date. No one on TeamBiden has so much as blinked in that direction. Nor do I believe for a moment that a President Biden would prioritize such an effort. Ultimately, such a task would require a clear, firm national goal. That would require something Biden simply lacks. Convictions.

A grand reset would also require the service of an American institution which no longer functions: the State Department. The past four administrations have alternatively neglected or gutted America’s diplomatic corps. It is largely incapable of being part of any solution without first undergoing a decade-long regeneration.

A grand reset would also require an American institution which is likely to be hostile to a Biden administration: the Senate. The Founding Fathers designed the Senate to act as a brake to prevent policy from evolving too quickly. One-third of the Senate faces election races every two years, so full turnover is sooooo sloooow. The Senate regularly reflects American politics as it exists…a decade in the past. In addition, each state gets the same two senators regardless of population – a measure designed to prevent larger states from trampling smaller states. That means more rural, lower-population states are more heavily represented. More rural, lower-population areas tend to prefer Trump over Biden.

For Biden to have a working majority in the Senate he needs to flip at least four seats. It is possible of course, but highly unlikely. (Recall that when the 2018 midterms delivered Trump a sound thumping at the national, state and local levels, Trump-aligned Republicans gained seats in the Senate.) The point of this constitutional detour is that the Senate is the institution that ratifies treaties, a classification that includes all the various agreements that underlay America’s Order-era structures: NATO, NAFTA, the United Nations, the WTO, the Japanese alliance, the International Monetary Fund, and so on.

A grand reset would also require time, which would also be in short supply. A President Biden would spend the first six months dealing with coronavirus and a series of legal reforms that address issues of accountability designed to Trump-proof future elections. Add in little things like summer breaks and in the most aggressive case scenario a President Biden couldn’t even begin any sort of new global effort until 2022. And don’t forget that the domestic issues Biden wants to prioritize also require the Senate. In the highly likely outcome that Biden’s domestic hopes are dashed on the Senate’s shoals, anything global is likely to be pushed not so much to the back seat, but to be abandoned on the side of the road.

For a good time, you too can play with electoral and Senatorial politics at https://www.270towin.com/.

If you enjoy our free newsletters, the team at Zeihan on Geopolitics asks you to consider donating to Feeding America.

The economic lockdowns in the wake of COVID-19 left many without jobs and additional tens of millions of people, including children, without reliable food. Feeding America works with food manufacturers and suppliers to provide meals for those in need and provides direct support to America’s food banks.

Food pantries are facing declining donations from grocery stores with stretched supply chains. At the same time, they are doing what they can to quickly scale their operations to meet demand. But they need donations – they need cash – to do so now.

Feeding America is a great way to help in difficult times.

The team at Zeihan on Geopolitics thanks you and hopes you continue to enjoy our work.

DONATE TO FEEDING AMERICA