FOR MORE ON THE FUTURE OF EAST ASIA, SEE DISUNITED NATIONS

Today, we’re looking at another region that the US will continue to keep tabs on – East Asia. This is one of those regions that will be plenty exciting in coming years, so let’s jump in.

Let’s start with the regional allies – Japan and Australia. Together with the US, these three countries have formed a trilateral alliance, which will help shape the power balance in the Pacific. Australia has been a close ally for decades and will continue to be just that. Japan is a more recent member of Washington’s inner circle and has joined for one big reason – China.

Japan, Australia and the US partnership has struck a strategic balance of power with Russia and China. This region’s future will depend upon where other regional powers decide to place their allegiance. Given China’s internal challenges and Russia’s apparent problems, it could (will?) turn chaotic very quickly.

We’ll be watching the dynamics unfold in East Asia over the coming years, and I expect no shortage of excitement.

Here at Zeihan On Geopolitics we select a single charity to sponsor. We have two criteria:

First, we look across the world and use our skill sets to identify where the needs are most acute. Second, we look for an institution with preexisting networks for both materials gathering and aid distribution. That way we know every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence. Then we give what we can.

Today, our chosen charity is a group called Medshare, which provides emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it. Until future notice, every cent we earn from every book we sell in every format through every retailer is going to Medshare’s Ukraine fund.

And then there’s you.

Our newsletters and videologues are not only free, they will always be free. We also will never share your contact information with anyone. All we ask is that if you find one of our releases in any way useful, that you make a donation to Medshare. Over one third of Ukraine’s pre-war population has either been forced from their homes, kidnapped and shipped to Russia, or is trying to survive in occupied lands. This is our way to help who we can. Please, join us.

TranscripT

Hey everybody. Peter Zeihan here, we are continuing our Post American series about what the world will look like, where the hotspots will be after the United States for trenches from its current position. Coming to you from the Eagle’s Nest wilderness just below Gore Lake. And today we are going to discuss the East Asian rim. This one is a little bit of an anomalous issue considering the series.

But whatever in that, this is an area that the Americans are going to remain very engaged in. Part of it, it’s about managing the Chinese decline, but in part it’s because the United States has a couple of very powerful, creative, capable allies that Americans appreciate. The first one is Australia, which is arguably the staunchest ally of the United States has, and it is always for two years at least served as a bit of a a deputy for American interest in Southeast Asia, which is a region that the United States is interested in, but has never really had the time to give the amount of attention that it deserves.

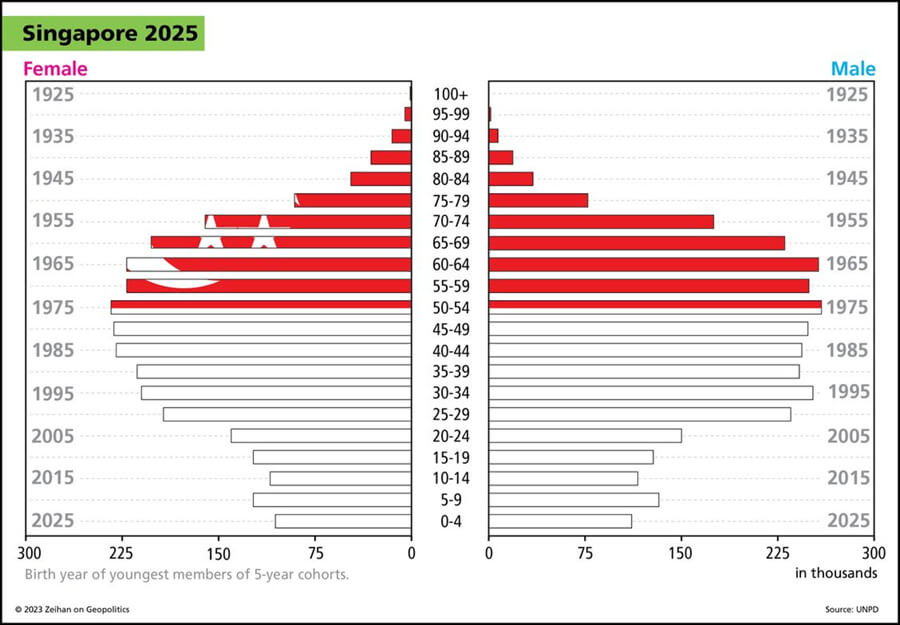

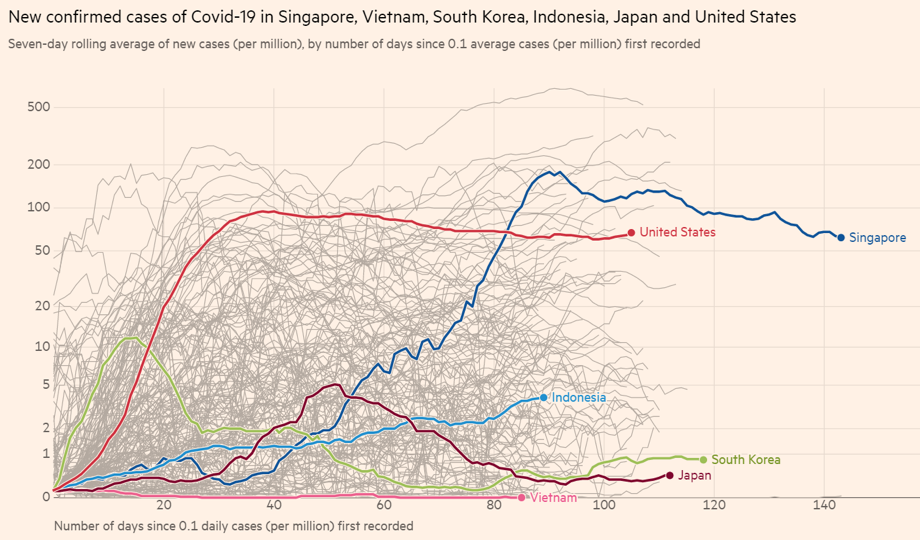

And that’s where the Australians come in. They’ve got excellent relations with most of the countries in the region, most notably Singapore and Indonesia. And then of course you’ve got New Zealand. There is a sidekick. Anyway, part of the reason that the United States has given nuclear powered submarines and a free trade deal to the Australians is because they’ve been so loyal and so long in areas that are out of theater.

They participated in Vietnam and Korea, they participate in Iraq and Afghanistan. They’ve always been there because they know at the end of the day, if they don’t have a partnership with the Americans, then they are on their own and they can read a map and they realize they’re wildly outnumbered in the region. So it is a strategy that they’ve been following for decades, the strategy that has borne a lot of fruit and is a strategy that will continue to serve them well into the future.

The other country is more of a newcomer, and that’s Japan. Now, throughout the Cold War, the Japanese were a bit combination of seething and shell shocked. They had been defeated soundly in World War Two. They had been nuked twice, which was something that didn’t happen to Nazi Germany. And the postwar settlements were, if anything, harsher on the Japanese than they were on the Germans.

And so there’s always this lingering nationalist ideal in Japan that wanted to move beyond the American Alliance network of the Cold War. But between the defeats, the occupation, American military force and the Soviets and the Chinese right there, they never really had that choice. Well, over the last 15 years, politics in Japan have evolved. It’s not that the nationalism has gone now, but the Chinese have become a much more clear and present danger than they thought the Chinese could ever be.

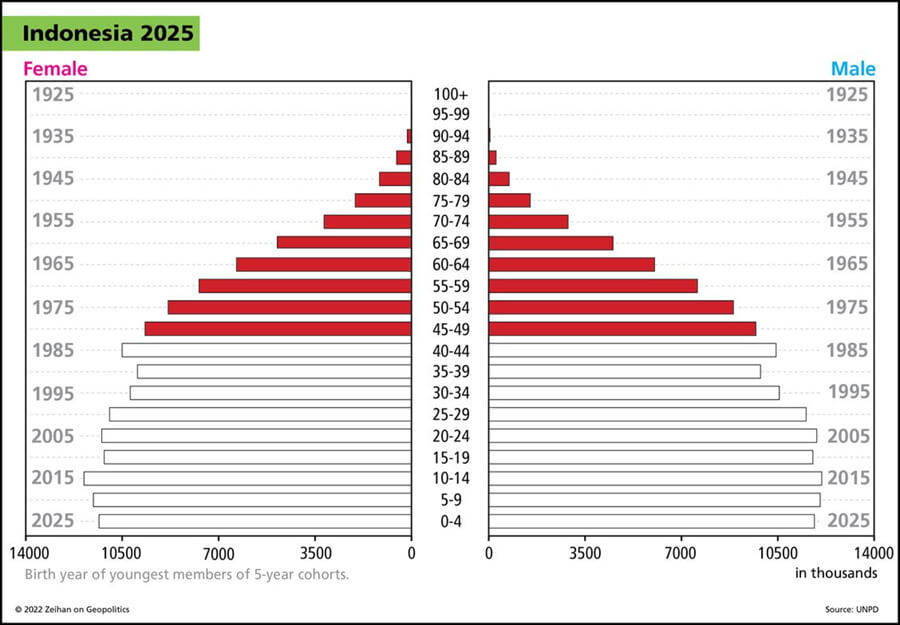

And the Russians, with their weakness in the Ukraine war, are showing themselves to be wobbly, which means that the Japanese have become very thoughtful about what their possibilities might become, that some things may not be what they thought. Some might be harder. Some might be easier. And in that sort of mindset, when you’re dealing with a demographic that is in terminal decline, you realize you probably are not going to be able to go it alone.

So it’s best to look for partners who are going to see the world through a similar lens, and that has led them willingly back to the United States over the course of the last 15 years. The Japanese have built a pair of very large carriers, quite super carriers, but the aircraft that operate from them are the Joint Strike Fighter that is made in the United States and the Japanese getting closer and closer and closer and managed to strike a deal both with the Trump and with the Biden administration on the future of bilateral relations.

So it’s not that Japan is not capable. It’s the second most powerful navy in the world by most measures. It’s that Japan has chosen that rather than going it alone, it’s opening the door on a protracted partnership with the United States and with Australia, and that puts major American power at three points of the Pacific bracketing nicely where the Russians are and where the Chinese are.

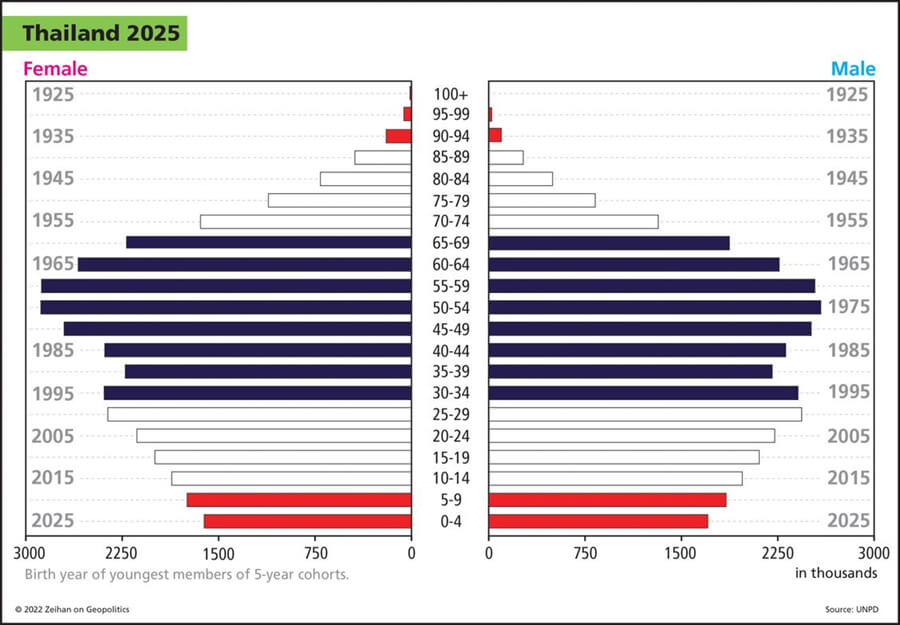

So for the future of this region, it’s going to come down to how powers do or do not get along with the Trilateral Alliance. Some, like the Chinese, are destined to break not probably because of military confrontation, but because of their own internal issues, which means this is going to be a zone of chaos. Opportunity carpetbagging for those of you who bothered to learn Mandarin or something like that.

It’s going to be impossible to put troops on the ground and stabilize something the size of China, even if you wanted to. So it’s probably just going to be a security black hole for a good long time. And then there’s other powers like Taiwan or Korea that get along pretty well with the United States and to a lesser degree, the Japanese, but are going to have to decide just how hand-in-glove they want to work.

This is one of those things that popped up earlier this year when the Biden administration had the Japanese and the Koreans to Camp David to basically hammer out a peace deal that dates back not to World War Two, but to 1905 when the Japanese occupied and colonized the Koreans. If if if the Japanese and the Koreans can agree to get along, then we can have a mini globalization in East Asia, because Taiwan’s almost a rounding error at that point that also involves Southeast Asia.

But if the Koreans decide to go a different direction, then there’s a very big security problem because the Japanese will never be secure so long as the Koreans are a hostile power. So a lot of this remains a an act in progress. But we’re starting to see the outlines of a post Russia, post Chinese Asia already. And it speaks with an Australian in the Japanese accent.

All right. That’s it. By.