Let’s take a breather from the Russian Reach series and talk about something going on in Africa. Specifically, we’ll be looking at the escalating conflict between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Rwanda is a small but densely populated country, with a history of sending militias into neighboring Congo. This latest offensive led by M23 has been making a significant push toward the Katanga region, home to one of the world’s largest copper-cobalt deposits. Since the DRC produces roughly 75% of the world’s cobalt, this has obviously caught the attention of some bigger players.

China and South Africa are the main operators in the region as of now, but the Congolese government has offered the US exclusive oversight of the copper-cobalt belt in exchange for protection against Rwanda. Should Trump care to set out on this endeavor, it will be a large undertaking. The US would have to partner with Angola or Mozambique to tap into South Africa’s transportation network or build new infrastructure in eastern Congo (which would be challenging).

This conflict could spiral into a major war – one akin to previous conflicts in the region, killing millions and involving numerous foreign powers. And given the rising tensions between the US and China, we could be staring down a geopolitical flashpoint.

Here at Zeihan on Geopolitics, our chosen charity partner is MedShare. They provide emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it, so we can be sure that every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence.

For those who would like to donate directly to MedShare or to learn more about their efforts, you can click this link.

Transcript

Hey, everybody. Peter Zeihan here coming to you from Colorado. And today we’re talking about something completely different, specifically what’s going on with Rwanda and Congo. And I think that I’m gonna make this relevant. Okay. Who are they? First of all, Ronda is a tiny, tiny little country. One of the little landlocked ones, just to the west of the Horn of Africa and Congo is the opposite.

This huge country in the heart of equatorial Africa really only has a tiny little frontage, so it might as well be landlocked. But it’s larger than all of the countries of Western Europe combined. What do they have in common? Not a lot. Their borders are demarcated because of the way that the colonial era ran. And so, especially in the case of Congo, it makes very little sense.

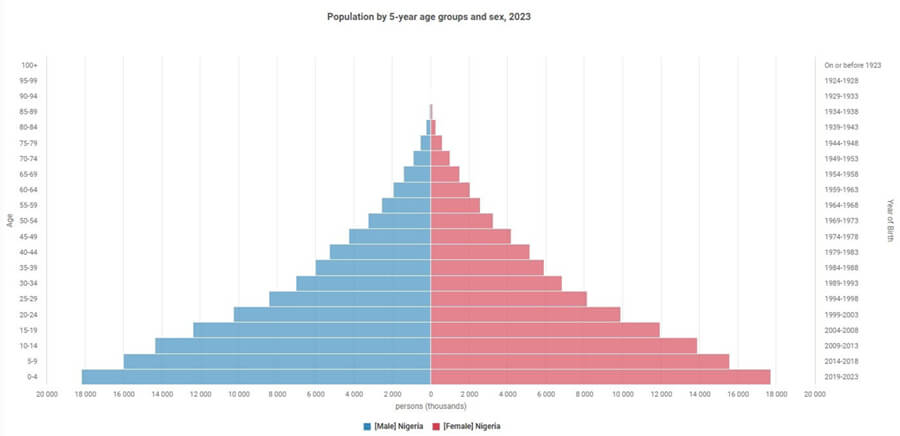

But what Rwanda has going forward is it’s just in the right spot with volcanic soil, just enough upland to keep the humidity under control. That is incredibly fertile. So it’s probably the densest population density on the continent once you’ve removed Egypt, which is a very special case. As a result, it always has a high fertility rate and generates a lot of populations.

And it’s generally led by people who are not particularly nice. And so every once in a while, they send an army across their borders to muck with somebody else for whatever reason. The world has called that genocide in the past. And so the way that the Rwandans have adapted is by generating a militia that they don’t control, that just happens to go out and do things that they like to get done.

It’s complete pretexts called M23. Anyway, M23 has been operating in eastern Congo now for a few years, and in recent weeks actually managed to capture a couple significant cities of size. And they’re continuing on the march. And there’s really nothing Congolese can do about it, because Congo’s territory is a shit show. It’s jungle, it’s mountainous, it’s it’s forested, it’s steep, it’s remote.

There are very few roads in the country. And so while Kinshasa, the nominal capital all the way in the west, is officially controls all of it, you really had these series of regional capitals that operate like little fiefdoms. It’s a very holy Roman Empire. Well, what is happening now is that the Rwandan groups M23 are basically breaking out of their region in the northeast part of the country and moving further south and further west, and that is pushing them towards the Katanga region, which is the site of Congo’s copper cobalt belt, which is one of the world’s richest mineral sources, specifically providing roughly 70 to 75% of the world’s cobalt.

And if you want to live in a world that involves batteries in some way, when we’re talking like electric vehicle batteries or grid cell batteries, you have to have cobalt. So all of a sudden, this has gotten very, very real. The last time Rwanda did this at scale, they overthrew the Congolese government. And imposed one of their proxies in charge, and he ruled the country until about Fugees 2008 2018.

It’s been a hot minute, but, for a while, and that happened back in 1999 to 2001. You guys may remember the name Mobutu. He was the guy who took over for the Belgians after they left. He ran the place into the ground until that eventually the Rwandans ousted him. Anyway, we have a different government now, but there are painfully aware of when Rwanda decides that they want to oversee you through your government.

They can, because the Rwandans are supplied, they’ve got cash and they have the unofficial blessing of the international community for a weird reason. Because if you remember back, there was, a series of genocides not too long ago in Rwanda, and the guy who eventually emerged and, on top of that, a guy by the name of Kagame, basically made nice with the Western institutions, in order to and ended the genocide.

So, you know, I don’t mean to take away that from him, but he’s borderline genocidal himself. And now he’s turning his tender mercies onto Congo. So far, no one has called him to the carpet on it. I really doubt the Trump administration is going to do that. In other news, you have to watch who is ultimately going to end up control this belt.

Right now, the Chinese are probably the largest operators in the cobalt space, whereas South Africa plays a role in transport because they control the rail network that takes the ore from the copper side of things, which is a lot bulkier than the cobalt and takes it down to their ports in South Africa for shipping out, no matter what shape the world is in, five, ten, 15 years from now, the materials from.

Congo are going to be central. The world does not have enough copper. The United States needs to massively improve its industrial plant even before you consider the Green Revolution. And everything with the Green Revolution revolves around electricity. So you need it for the wiring and the batteries and everything else. And then, of course, the copper itself.

So this is a space to watch. And I just had to shove this in there between all the Trump stuff that’s going on.

Well, shit, there’s a trump angle to this one too. In the time that it took me to walk back to download this, the Congolese government has offered Donald Trump personally that if they come and protect Congo from Rwanda, that they will sign a deal that gives the Americans oversight and access to the entire copper cobalt belt. Something like the copper cobalt belt is in the southeastern part of the country.

It is not well linked up to the rest of the country at all. This is one of the reasons why the Rwandans, are making a play for it, because the Congolese really can’t defend it. The only infrastructure in the area that really does link it to the outside world goes south down the spine of southern Africa into South Africa.

But South Africa, no longer has the expeditionary military force to project power up that line. And the only other country in the region that really has military power at all would be Angola. And they’re on the wrong side of the jungles as well. So if if the United States were to do this, we’d have to do one of two things.

Number one, it would have to cut a deal with either Angola or Mozambique or both to access that South African spine in order to come in from the south and probably be the easiest way. And the Biden administration did make a lot of progress with Angola on firming up the relationship at the detriment of China. The second option would be cut a deal with consortia.

You know, Congo’s nominal government and build out the infrastructure that would be necessary to go in from the east. The Congo option would be the illegal option. The Angola or the Mozambique option would be the imperial option. And before you say anything about Donald Trump and imperialism, just keep in mind we are talking here about the deep, dark heart of Africa.

So the infrastructure is non-existent. The militants are everywhere. And the last time we had a major war in this region, which was just in the 90s, in the 2000, at least 2 million people died and 17 countries were involved. And that’s before you consider, say, outside powers like China, the United States. So if you are looking for a long, drawn out, messy approach to getting critical minerals, this might be just your speed.